Using Tensor Cores is now a prerequisite to get anywhere near peak performance on NVIDIA GPUs. In this post we work through the process of developing an efficient Tensor Core matrix multiplication kernel targeting the Ada architecture.

We start with a naive implementation and by incorporating techniques used in CUTLASS1, finish with a kernel that matches cuBLAS performance (on one particular problem specification):

| Kernel | Execution Time | TFLOP/s | % cuBLAS | % 4090 peak |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cublasGemmEx | 895 us | 153.6 | 100% | 93.0% |

| Kernel 1.0: Naive mma | 4680 us | 29.4 | 19.1% | 17.8% |

| Kernel 1.1: Naive + 2x tiling | 2400 us | 57.3 | 37.3% | 34.7% |

| Kernel 2.0: Permuted shmem | 1080 us | 127.3 | 82.9% | 77.0% |

| Kernel 2.1: Permuted shmem + register tweak | 1030 us | 133.4 | 86.9% | 80.8% |

| Kernel 3.0: N-stage async pipeline | 1000 us | 137.4 | 89.5% | 83.2% |

| Kernel 3.1: N-stage + 4x tiling | 895 us | 153.6 | 100% | 93.0% |

In the process we’ll learn about the mma, ldmatrix and cp.async PTX instructions, how CUTLASS’s permuted shared memory layout avoids bank conflicts and how to set up an n-stage global to shared memory pipeline. The code is written as simply as possible: the aim is ease of understanding rather than generality or robustness.

As may be clear already, this post was heavily inspired by Simon Boehm’s great worklog on optimizing a CUDA matmul kernel2.

Problem Definition

We’ll focus on one particular problem shape: M=N=K=4096, for fp16 A/B and fp32 C/D. This operation is 2*4096^3 = 137.4 GFLOP3 (conventional to count one FMA as 2 FLOP) and the peak fp16/32 throughput of the RTX 4090 is 165.2 TFLOP/s4, so the lower bound on kernel execution time is ~830 us.

We can use the peak throughput number to deduce how many cycles one Tensor Core instruction takes to complete (latency). All our kernels will use the PTX m16n8k16 mma instruction, this is the largest Tensor Core matmul supported on Ada so it’s reasonable to assume the peak throughput is obtained using this instruction.

The m16n8k16 operation is 2*16*8*16=4096 FLOPS, and there are 512 Tensor Cores on the RTX 4090, hence computing one mma on all Tensor Cores gives 2,097,152 FLOPS. Given the peak throughput of 165.2 TFLOPS/s at the boost clock of 2520 MHz, it must take 12.7 ns = 32 cycles for the m16n8k16 mma operation to complete. This is roughly consistent with empirical benchmarks5.

Our problem shape of M=N=K=4096 requires 256x512x256 = 33,554,432 individual m16n8k16 mma instructions, which is 65,536 card-wide waves of mmas. Hence in the best case, with no cycles stalled waiting for input, the minimum number of cycles this will take is 65,636 * 32 = 2,097,152, which is 832 us at the boost clock of 2520 MHz. Note this agrees with the number computed using peak throughput by definition as we computed the 32 cycle latency from the throughput.

Benchmarking Setup

As a baseline for performance we use the cuBLAS cublasGemmEx API with fp16 inputs andfp32 accumulation. This performs a M=N=K=4096 matrix multiply in 895 us which is a throughput of 153.6 TFLOPS/s, 93.0% of the RTX 4090’s peak.

How to accurately time CUDA kernel execution could fill an entire post but in summary either CUDA events or nsight-compute give broadly consistent results if you first lock the gpu and memory clocks. I used nsight-compute as it measures kernel execution more precisely than possible using events 6.

By default nsight-compute locks to the GPU’s base clock, but as I wanted to compare to the RTX 4090’s stated peak throughput I locked at the boost clock of 2520 MHz. Kernels were run 55 times, the first 5 runs discarded and average results on the remaining 50 reported.

sudo nvidia-smi -pm ENABLED

sudo nvidia-smi --lock-gpu-clocks=2550 # lock at boost clock

sudo nvidia-smi --lock-memory-clocks=10501 # max for RTX 4090

ncu -s 5 -k $my_kernel_name --clock-control none --print-summary per-gpu $my_executable

Benchmarks were run on Pop!_OS 22.04 LTS, CUDA Toolkit Version 12.4, CUDA Driver Version 550.67.

Aside: Tensor Core Matrix Multiply APIs

There are three separate Tensor Core matmul APIs in CUDA/PTX:

- WMMA: High level API available in both CUDA and PTX

- MMA: Lower level API just available in PTX

- WGMMA: sm_90 only API that operates on warp-groups (consecutive groups of 4 warps). Just available in PTX

All kernels in this post use the PTX mma API. wgmma is not an option as I am using an Ada architecture GPU. I chose mma over wmma as mma is a lower level API and my aim is to build an understanding of the underlying Tensor Core operations. Using mma also reportedly delivers higher performance than wmma though that comparison is old7.

Kernel 1.0: Naive mma kernel

The first kernel is a naive implementation resulting from reading the mma instruction documentation and handling data movement from global memory to registers in the simplest way possible.

In the Ada architecture there are 4 warp schedulers per SM, each with their own Tensor Core. Hence we want at least 4 warps per thread block (not strictly required as multiple thread blocks can run concurrently on one SM). In this kernel we use a 16x16 thread block, containing 8 warps. Each warp computes one 16x8 output tile and we arrange the warps in a 2 row x 4 column grid, so that each thread block computes a 32x32 output tile.

// arrangement of warps in output tile

// (warp_0 | warp_1 | warp_2 | warp_3)

// (warp_4 | warp_5 | warp_6 | warp_7)

There are multiple mma instructions for different data types and matrix shapes. As mentioned previously, in this and all subsequent kernels we’ll use

mma.sync.aligned.m16n8k16.row.col.f32.f16.f16.f32

which performs (per warp) the matrix multiplication D = A * B + C where A is a 16x16 fp16 matrix, B is 16x8 fp16 matrix and C/D are 16x8 fp32 matrices.

As mma is a PTX instruction, calling it from CUDA code requires using inline PTX which we wrap in a helper function:

__device__ void mma_m16n8k16(const unsigned *A, const unsigned *B, float *C, float *D) {

asm(

"mma.sync.aligned.m16n8k16.row.col.f32.f16.f16.f32 "

"{%0,%1,%2,%3}, {%4,%5,%6,%7}, {%8,%9}, {%10,%11,%12,%13};\n"

: "=f"(D[0]), "=f"(D[1]), "=f"(D[2]), "=f"(D[3])

:

"r"(A[0]), "r"(A[1]), "r"(A[2]), "r"(A[3]),

"r"(B[0]), "r"(B[1]),

"f"(C[0]), "f"(C[1]), "f"(C[2]), "f"(C[3])

);

}

The mma instruction is warp-wide, each of the 32 threads provides 8 fp16 elements from A, 4 fp16 elements from B and 4 fp32 elements from C, and recieves 4 output fp32 elements from D. The 8 fp16 elements of A are packed into 4 32 bit registers, and similarly the 4 elements of B into 2 32 bit registers.

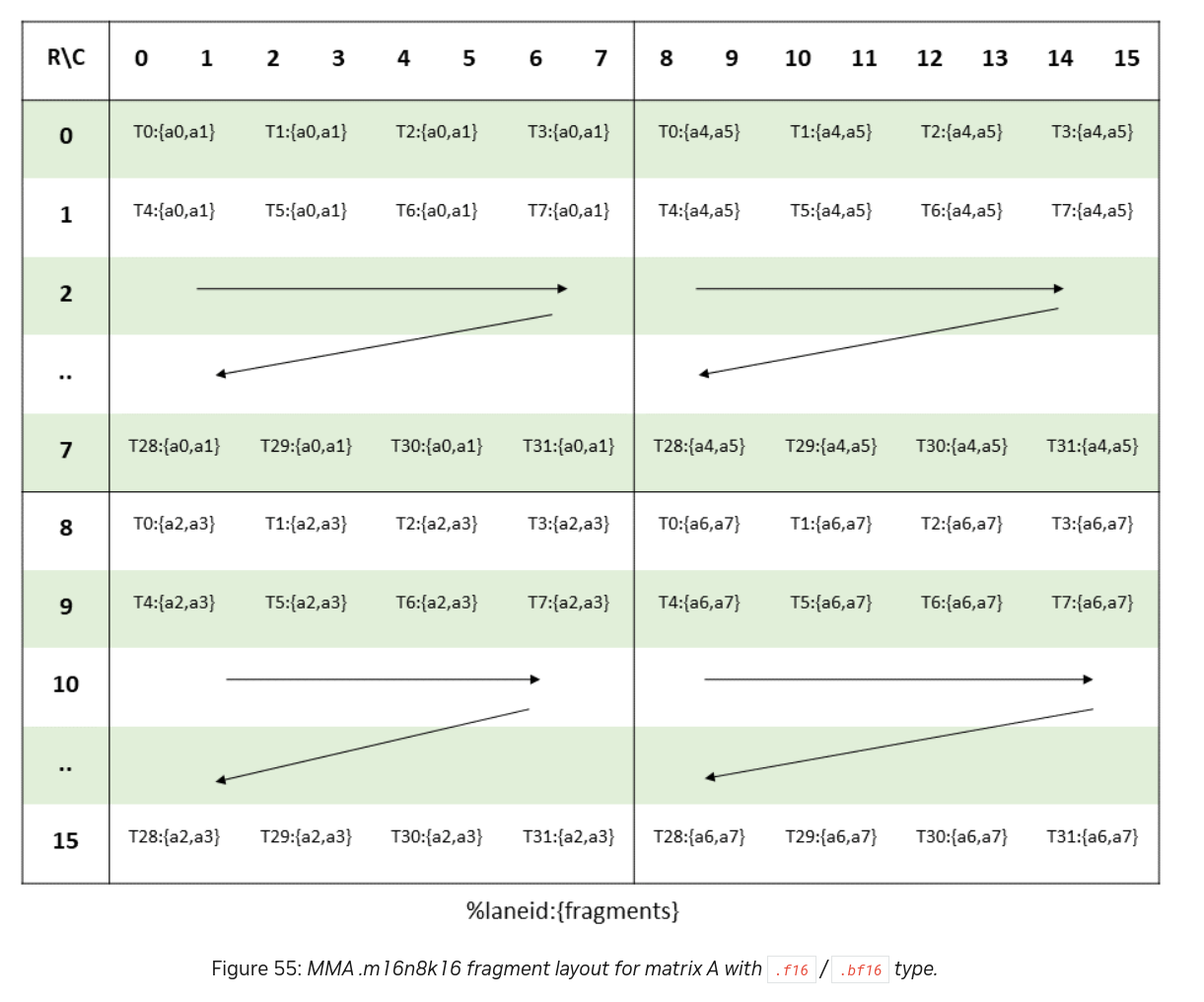

The matrix elements held by each thread in its registers are called a matrix fragment, and the required mapping from thread ID to fragments for A is shown below:

A is split into 4

A is split into 4 8x8 submatrices, and each submatrix is split across the warp in a row major fashion which each thread holding two fp16 values in one of its 32 bit registers. Mappings for B, C & D are defined similarly and can be found in the PTX docs.

We will later use the ldmatrix instruction to load fragements to registers, but for now we’ll do this per thread to demostrate the mapping. The main loop of Kernel 1.0 contains the code to load matrix fragments to registers and call the mma instruction.

for (int kStart=0; kStart < K; kStart += K_BLOCK) {

// load from global to shared memory

for (int m=0; m < 2; ++m) {

As[m*K_BLOCK + ty][tx] = A[(mBlock + ty + m*K_BLOCK)*K + kStart + tx];

}

for (int n=0; n < 2; ++n) {

Bs[ty][n*K_BLOCK + tx] = B[(kStart + ty) * K + nBlock + n*K_BLOCK + tx];

}

__syncthreads();

// load from shmem to fp16 registers

aReg[0] = As[mWarp + groupID ][groupLaneID*2 ];

aReg[1] = As[mWarp + groupID ][groupLaneID*2 + 1];

aReg[2] = As[mWarp + groupID + 8][groupLaneID*2 ];

aReg[3] = As[mWarp + groupID + 8][groupLaneID*2 + 1];

aReg[4] = As[mWarp + groupID ][groupLaneID*2 + 8];

aReg[5] = As[mWarp + groupID ][groupLaneID*2 + 9];

aReg[6] = As[mWarp + groupID + 8][groupLaneID*2 + 8];

aReg[7] = As[mWarp + groupID + 8][groupLaneID*2 + 9];

bReg[0] = Bs[groupLaneID*2 + 0][nWarp + groupID];

bReg[1] = Bs[groupLaneID*2 + 1][nWarp + groupID];

bReg[2] = Bs[groupLaneID*2 + 8][nWarp + groupID];

bReg[3] = Bs[groupLaneID*2 + 9][nWarp + groupID];

// pack fp16 registers to u32 and call mma

unsigned const *aPtr = reinterpret_cast<unsigned const *>(&aReg);

unsigned const *bPtr = reinterpret_cast<unsigned const *>(&bReg);

mma_m16n8k16(aPtr, bPtr, dReg, dReg);

__syncthreads();

}

Performance

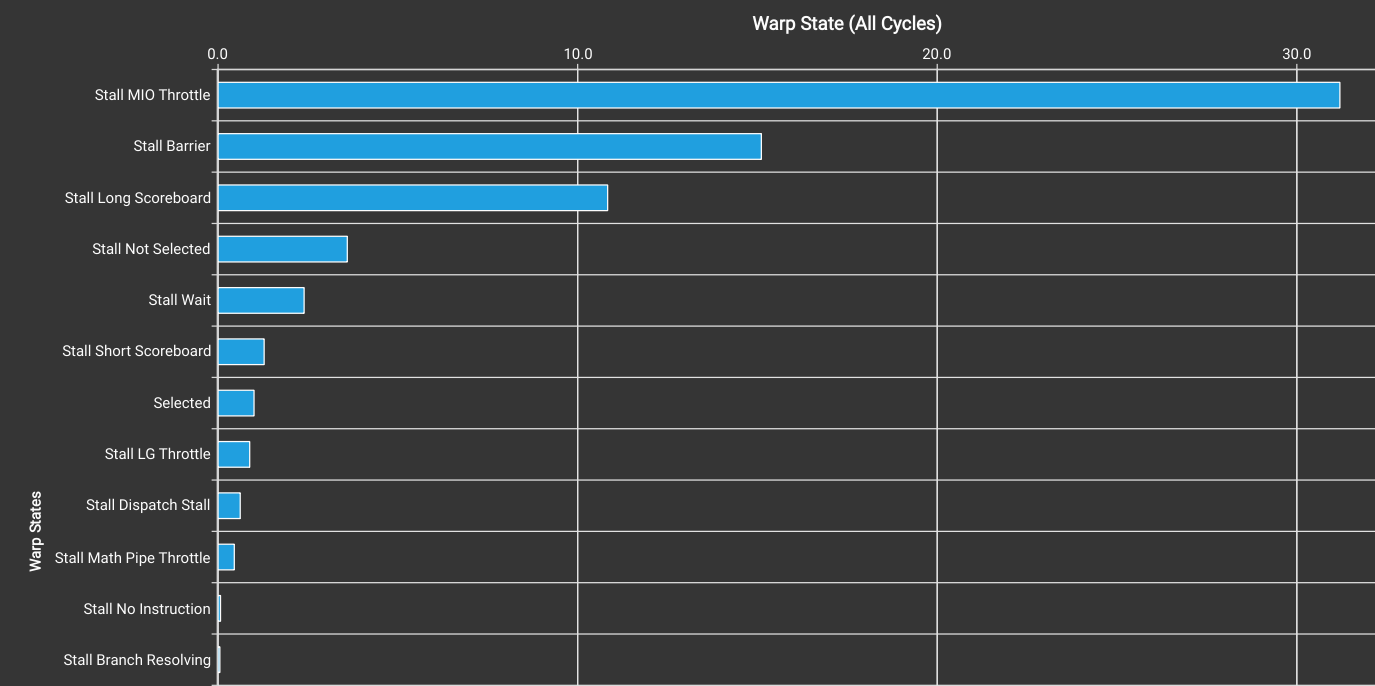

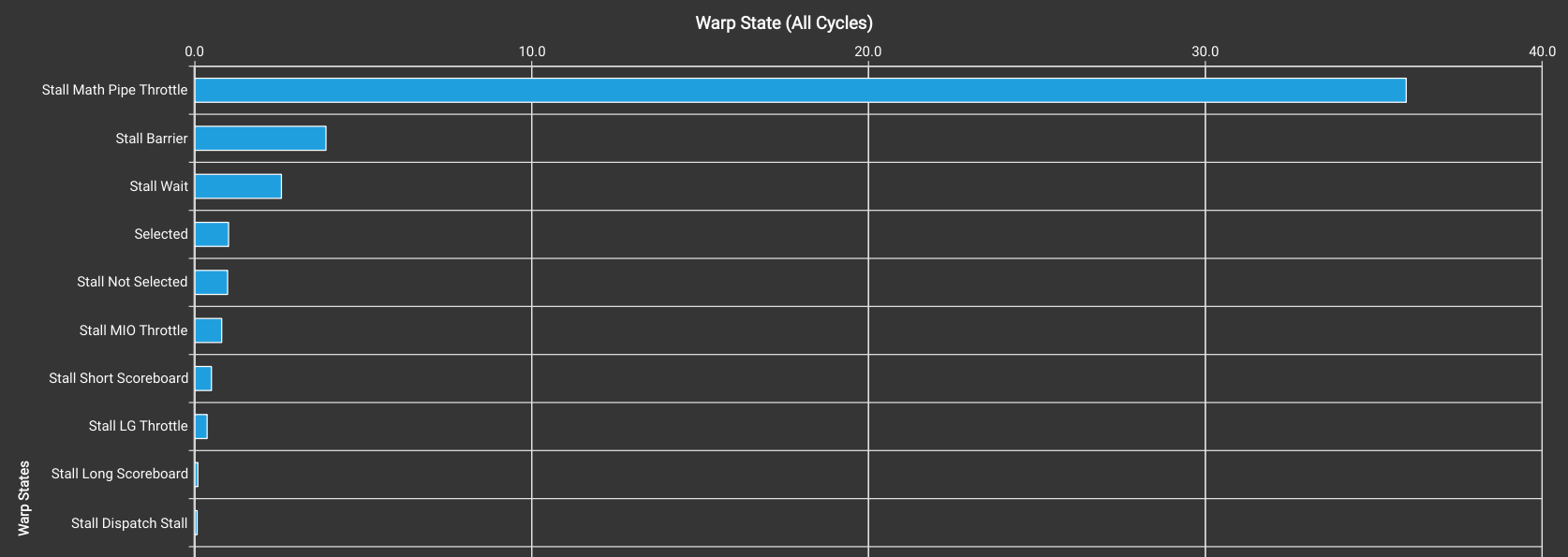

Kernel 1.0 has an execution time of 4.67 ms, giving a throughput of 29.4 TFLOP/s, 19.1% of cuBLAS and 17.8% of peak RTX 4090 performance. In fact it only achieves 35.6% of the RTX 4090’s peak FP32 performance, so a reasonably optimized non Tensor Core kernel would be faster. The reasons for the poor performance are:

- Each thread loads individual 16b values in an uncoalesced load pattern

- The loads from shared memory to registers have multiple bank conflicts

- Each element loaded is only used in the input to one

mmainstruction, so the ratio of memory access to computation is low

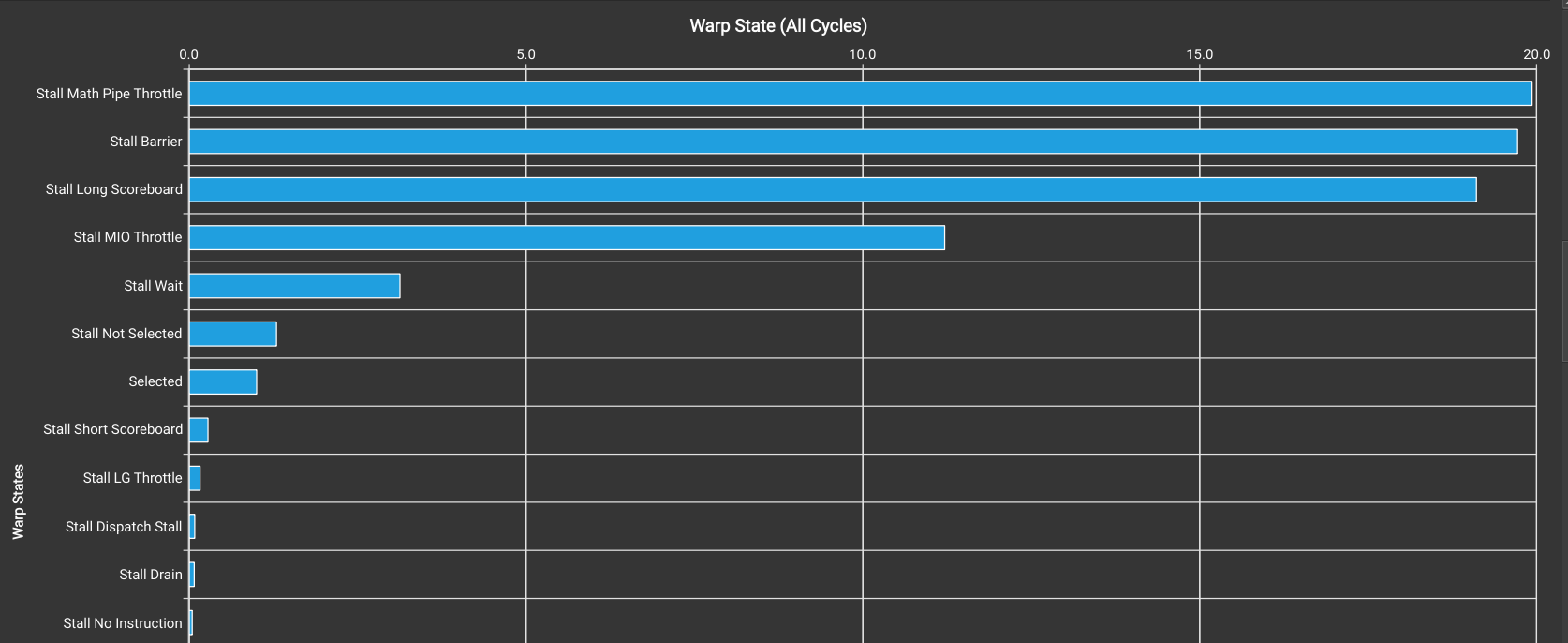

The Warp State Statistics chart in nsight-compute shows the impact of these problems: on average per instruction executed a warp spends 31 cycles stalled on shared memory throttles (MIO), 15 cycles stalled on barrier waits and 11 stalled on long scoreboard (global load) dependencies.

We can also use the profiler to query the count of mma instructions executed and elapsed cycles:

------------------------------------------- ----------- -------------

Metric Name Metric Unit Metric Value

------------------------------------------- ----------- -------------

sm__cycles_elapsed.avg cycle 11,787,459.33

sm__cycles_elapsed.max cycle 11,822,127

sm__cycles_elapsed.min cycle 11,739,016

sm__cycles_elapsed.sum cycle 1,508,794,794

smsp__inst_executed_pipe_tensor_op_hmma.avg inst 65,536

smsp__inst_executed_pipe_tensor_op_hmma.max inst 66,048

smsp__inst_executed_pipe_tensor_op_hmma.min inst 65,024

smsp__inst_executed_pipe_tensor_op_hmma.sum inst 33,554,432

------------------------------------------- ----------- -------------

The total number of mma instructions is 33,554,432 as calculated earlier, with 65,536 being computed on each Tensor Core. The number of cycles elapsed per mma was 11,787,459 / 65,536 = 179.9, so we are far from the 32 cycles best case.

The three problems described above will be addressed in Kernel 2: Point 1 by using vectorized and coalesced loads, Point 2 by using a permuted shared memory layout and Point 3 as each warp will compute multiple output tiles.

To isolate the impact made just by tiling vs the other changes, we add 2x tiling in the M and N dimensions in Kernel 1.1. In this kernel each warp executes 4 mma instructions meaning each thread block computes a 64x64 output tile. This reduces execution time to 2.40 ms, increasing throughput to 57.3 TFLOP/s, 37.3% cuBLAS, 34.7% peak performance.

In this kernel we use some of the techniques (vectorized loads and permuted shared memory layout) discussed in the GTC 2020 CUTLASS presentation1 to resolve the performance issues of Kernel 1. The memory layout diagrams in this section are taken from that presentation. The majority of the performance of the final kernel comes from the permuted shared memory layout introduced in this section.

Throughout this kernel we operate on uint4 128b vectors containing 8 consecutive fp16 elements in the K dimension of A and B. Working with 128b vectors is natural when using Tensor Cores as the fundamental Tensor Core operation is an 8 by 8 by 128b matrix multiply, i.e. each 128b vector forms one row of the input matrices. Using 128b vectors also means we can vectorize memory operations.

We keep the 16x16 thread block dimensions from Kernel 1. The main loop of the kernel is shown below:

// row / column indices when storing to shared memory

int storeRow = warpID * 4 + laneID / 8;

int storeCol = (laneID % 8) ^ (laneID / 8);

// row/column indices when loading from permuted shmem layout to registers

int loadRowA = (laneID % 16) / 2;

int loadColA = (laneID / 16 + 4 * (laneID % 2)) ^ (loadRowA % 4);

int loadRowB = (laneID % 8) / 2;

int loadColB = (laneID / 8 + 4 * (laneID % 2)) ^ (loadRowB % 4);

for (int k = 0; k < K/8; k += 4) {

As[storeRow][storeCol] = globalTileA[(warpID*8 + laneID/4)*K/8 + k + laneID%4];

Bs[storeRow][storeCol] = globalTileB[(warpID*8 + laneID/4)*K/8 + k + laneID%4];

__syncthreads();

// loop over the two (M/N=16, K=4) tiles of a and b

for (int m = 0; m < 2; m++) {

int mTile = m * 8;

for (int n = 0; n < 2; n++) {

int nTile = n * 4;

load_matrix_x4(aReg, (As[mWarp + mTile + loadRowA] + loadColA));

load_matrix_x2(bReg, (Bs[nWarp + nTile + loadRowB] + loadColB));

mma_m16n8k16(aReg, bReg, dReg[m][n], dReg[m][n]);

load_matrix_x4(aReg, (As[mWarp + mTile + loadRowA] + (loadColA^2)));

load_matrix_x2(bReg, (Bs[nWarp + nTile + loadRowB] + (loadColB^2)));

mma_m16n8k16(aReg, bReg, dReg[m][n], dReg[m][n]);

}

}

__syncthreads();

}

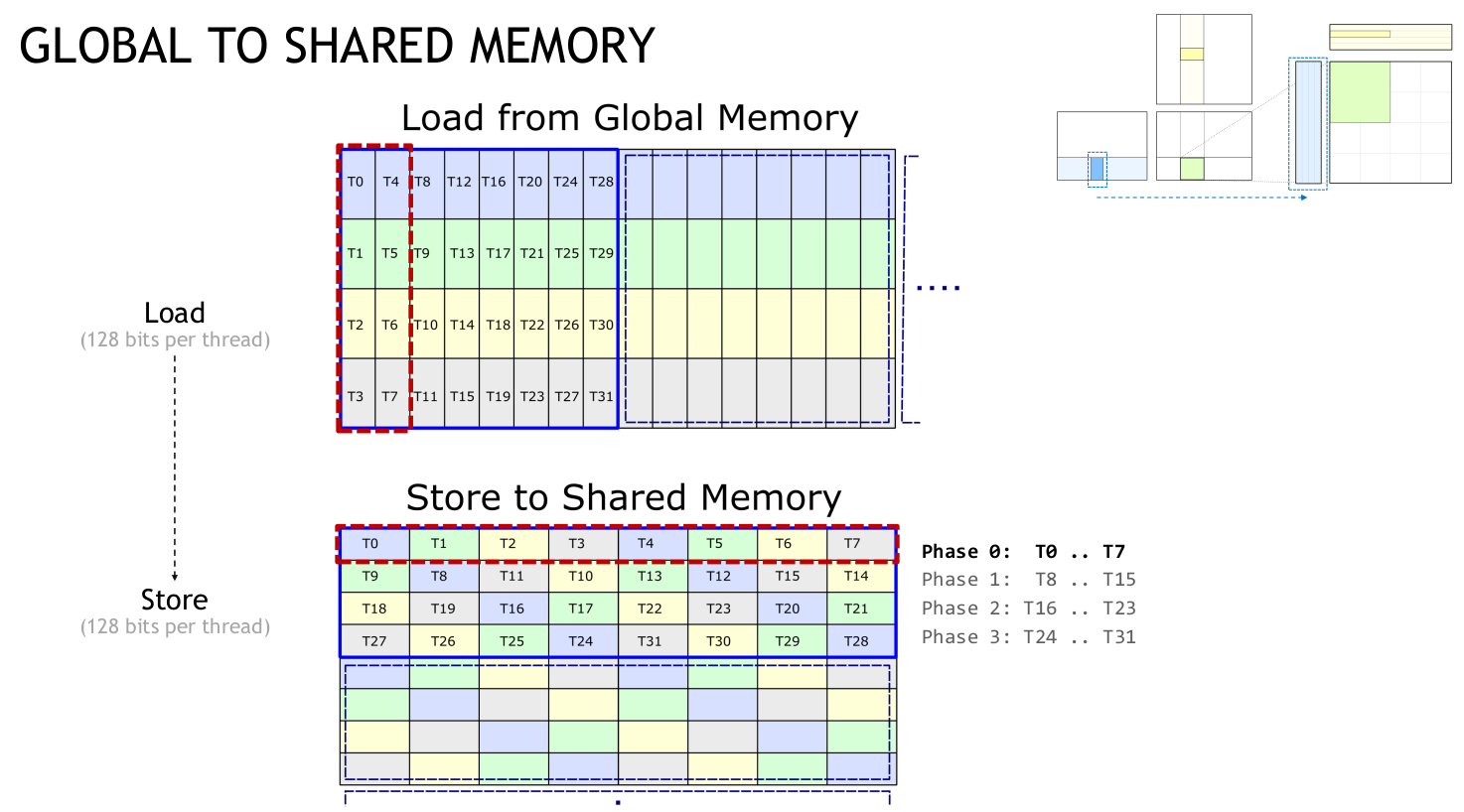

Looking first at the load from global to shared, each thread block loads A/B tiles of shape (M/N=64, K=4) uint4 values from global memory to shared memory in a K-major fashion (i.e. row-major for A and column-major for B), with consecutive threads loading consecutive uint4 values in the K-dimension using vectorized 128b loads. To coalesce these loads, the kernel requires A to be stored row-major in global memory and to be B stored column-major.

At the warp level, we load uint4 tiles of shape (M/N=8, K=4) containing 8 rows/columns of A/B each containing 4 uint4 values. This results in eight 64B memory transactions, each transaction reading two 32B sectors out of a 128B cache line containing four sectors in total.

This tile is stored in a uint4 shared memory array of shape (4, 8) with two K=4 row/column slices stored per shared memory row. This shared memory shape is used as shared memory has 32 banks which are each 4 bytes wide, hence a row of 8 uint4 values spans the 32 shared memory banks.

To avoid bank conflicts, threads which are part of the same memory request must not access addresses which map to the same bank. When each thread requests a 16B (128b) value, the warp level 512B request is split into 4 phases each consisting of 8 consecutive threads, as the max shared memory bandwidth is 32 banks * 4B = 128B. This means that it is sufficient to avoid bank conflicts within the 8 threads in each phase, rather within the full warp of 32 threads.

When storing to shared memory, the column indices for each row are permuted by XORing them with the row index: storeCol = (laneID % 8) ^ (laneID / 8). The store from global to shared would be bank conflict free without this permutation, but it is required to avoid bank conflicts when loading data to registers from shared memory.

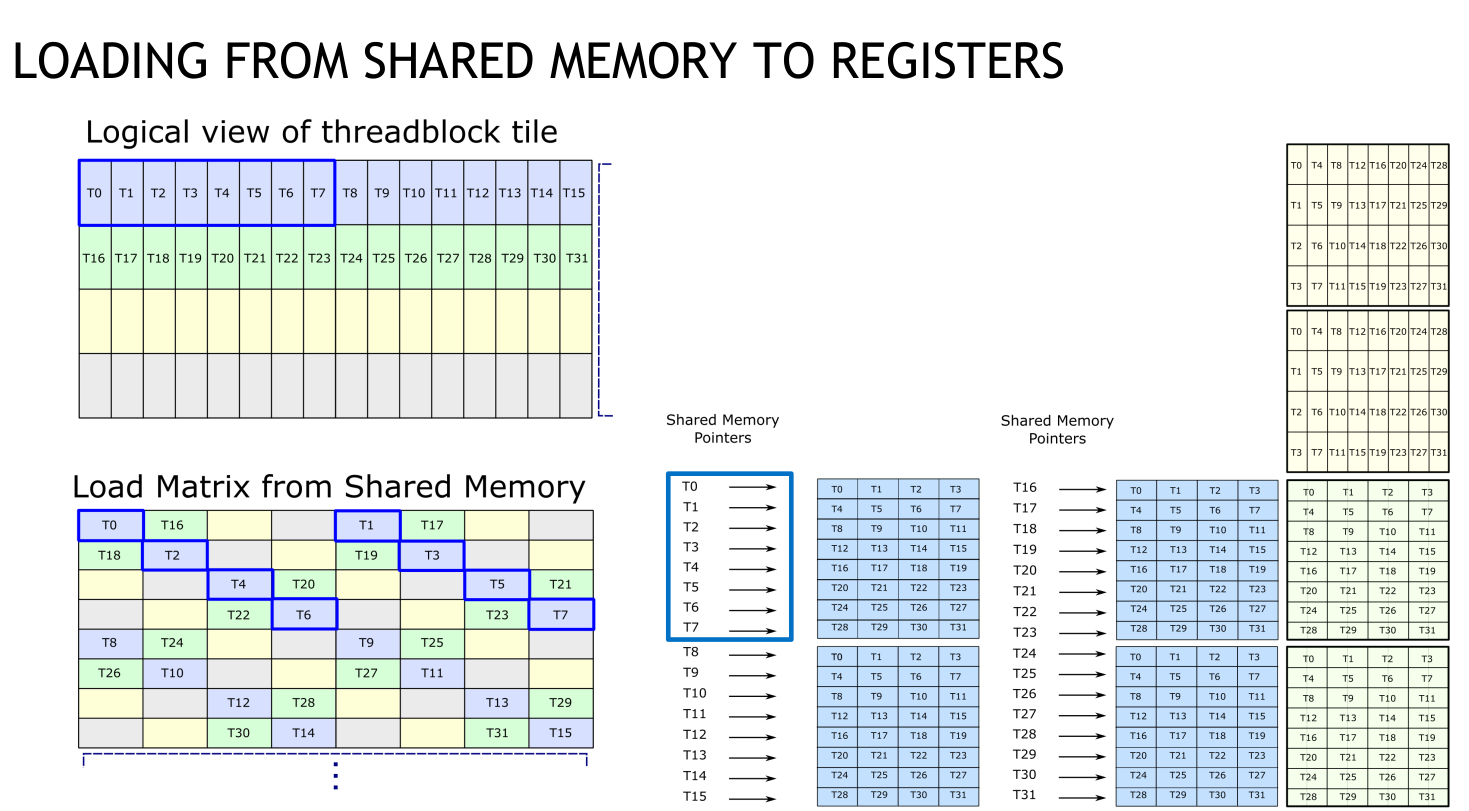

This diagram from 1 illustrates how one warp loads from global to shared using the permuted layout:

Once data is loaded to shared memory, each warp computes a matmul on a (M=32, K=4) tile of A and a (N=16, K=4) tile of B. As the mma instruction computes a M=16, N=8, K=16 matmul we split these tiles into two (M=16, K=4) tiles of A / (N=8, K=4) tiles of B and compute their products in a nested loop. At the innermost level of this loop, we first load the k=0..1 subtiles of the current A and B tiles into registers and compute their product using the mma instruction. We then load the k=2..3 subtiles and perform a second mma.

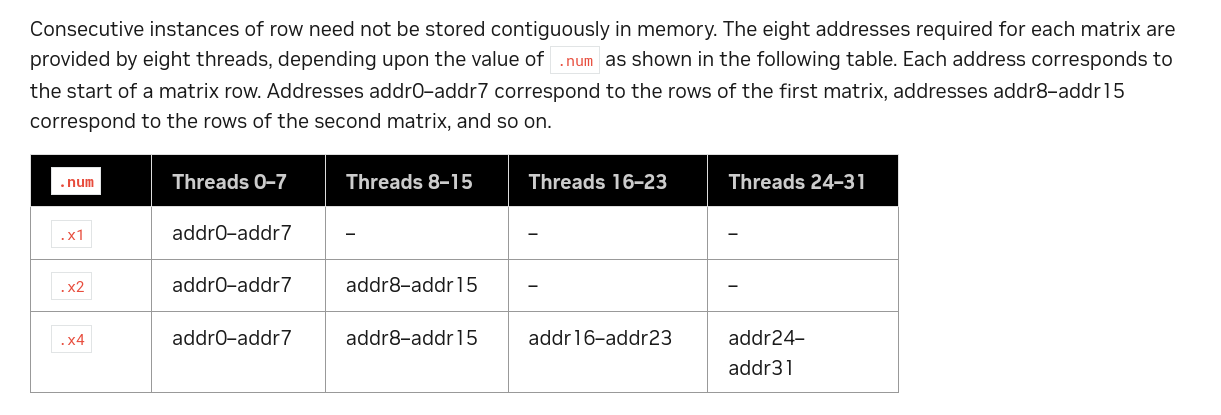

We use the ldmatrix PTX instruction to load these tiles from shared memory to registers. This warp-wide instruction loads 1, 2 or 4 8x128b matrices and stores each matrix in one 32b register per thread in the fragment layout discussed previously. Each 128b row of these matrices is stored in one uint4 vector in shared memory and each thread in the warp provides the address of one of these rows as described in the docs:

This means that to load a (M=16, k=0..1) subtile of A, we use the .x4 variant of ldmatrix, with threads 0..15 providing the addresses of the elements with indices m=0..15, k=0 and threads 16..31 providing the addresses of elements with indices m=0..15, k=1. Crucially, we permuted the layout of the tiles of A when storing to shared memory, and hence each thread needs to compute the address of its required element in the permuted layout.

Each (M=16, K=4) tile of A is stored in a 8 consecutive row subarray of the As shared memory array and each (N=8, K=4) tile of B is stored in a 4 consecutive row subarray of Bs. The mWarp, nWarp and mTile, nTile variables specify the start row of the subarrays of As, Bs for each warp / each iteration of the tile loop. Within each subarray the loadRowA/B, loadColA/B variables specify the location of the required element in the permuted layout.

The following diagram from 1 illustrates the locations in shared memory provided by each thread to ldmatrix when loading a (M=16, K=4) tile of A:

The elements of the k=0 slice of the subtile, loaded by threads 0..15 are shaded in blue. The elements loaded by threads 0..7 are all in distinct shared memory banks due to the permuted layout, as are those loaded by threads 8..15 and hence there are no bank conflicts.

This is also true for the k=1 slice which is shaded in green. If the permutation had not been applied, threads 0,2,4,6 would all access banks 0..3 and threads 1,3,5,7 would all access banks 16..19, causing multiple bank conflicts.

The elements shaded in yellow/gray belong to the k=2..3 slices, which are inputs to the second mma. The column indices for these slices can be computed efficiently from the column indices of the k=0..1 slices by applying xor 2 to those indices.

Loading the k=0..1 and k=2..3 subtiles of B is similar except that as the subtile dimension is (N=8, k=0..1) there are only 16 128b matrix rows to load. Hence we use ldmatrix.x2 which loads 2 8x128b matrices, using only the addresses in threads 0..15.

As with the mma instruction, we define helper functions load_matrix_x4, load_matrix_x2 to wrap the inline PTX. Looking at load_matrix_x4 as an example:

__device__ void load_matrix_x4(unsigned *destReg, uint4 *srcAddr) {

unsigned ptxSrcAddr = __cvta_generic_to_shared(srcAddr);

asm volatile(

"ldmatrix.sync.aligned.x4.m8n8.shared.b16 {%0, %1, %2, %3}, [%4];\n"

: "=r"(destReg[0]), "=r"(destReg[1]), "=r"(destReg[2]), "=r"(destReg[3])

: "r"(ptxSrcAddr)

);

}

Two things to note

__cvta_generic_to_sharedis a CUDA function that takes a standard C/C++ pointer, which is 64b, and converts to a 32b pointer as shared memory is a 32b address space- The

volatilequalifier is needed for this instruction: without it the loads do not get synchronized properly and threads end up with incorrect data, as I discovered after much painful debugging.

Once the main loop has finished, the output tile for each warp is contained in dReg, the output registers of the mma instructions. There is a stmatrix instruction to copy back from registers to shared memory but this requires sm_90 so we need to handle this ourselves. We write directly from registers to global memory, it may be possible to optimize this by writing first to shared and then writing to global in a coalesced pattern but that requires more shared memory and could reduce occupancy. I experimented with this but did not see a performance improvement.

Performance

Kernel 2.0 has greatly increased performance. Execution time is 1080 us, a throughput of 127.3 TFLOP/s which is 82.9% cuBLAS and 77.0% of RTX 4090 peak performance. We can make one minor tweak to the kernel to improve performance further. Currently we reload each tile of A for each tile of B, this reduces register usage but introduces redundant loads from shared memory to registers.

In Kernel 2.1 we only load each tile of A once, this improves performance to 1030 us, 133.4 TFLOP/s, 86.9% of cuBLAS, 80.8% peak. The elapsed cycles per mma for Kernel 2.1 is 38, much closer to the minimum of 32.

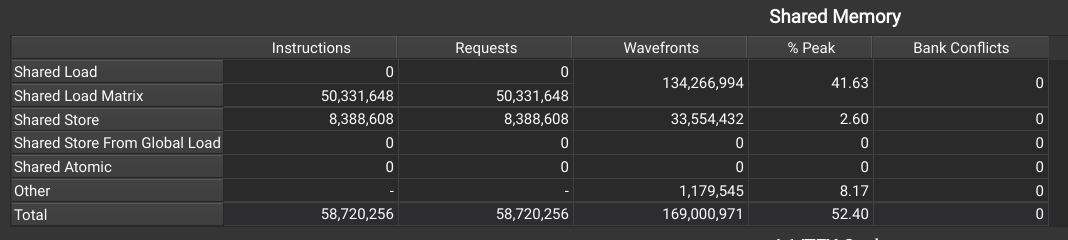

The permuted shared memory layout should make these kernels bank-conflict free and we verify this for Kernel 2.1:

Looking at the warp stats shows that the most frequent cause of stalls is now waiting for the Tensor Cores to be free - this is good!

There are still considerable number of barrier and long scoreboard stalls, which we’ll address in Kernel 3.0 by introducing an n-stage pipeline from global to shared memory using the cp.async instruction.

There are asynchronous copy APIs both in CUDA (cuda::memcpy_async) and PTX (cp.async). The cuda::memcp_async API does not support copying with a permuted layout and hence we use the PTX cp.async API. As before we define a wrapper function for the inline PTX call:

__device__ void cp_async(uint4 *dstAddr, const uint4 *srcAddr) {

unsigned ptxDstAddr = __cvta_generic_to_shared(dstAddr);

asm volatile("cp.async.cg.shared.global.L2::128B [%0], [%1], %2;\n"

:: "r"(ptxDstAddr),

"l"(srcAddr),

"n"(16));

}

The final "n"(16) input is the number of bytes to copy, and needs to be a compile time constant.

We can then use this function to replace the global to shared load:

// Replace this

As[storeRow][storeCol] = globalTileA[(warpID*8 + laneID/4)*K/8 + k + laneID%4];

Bs[storeRow][storeCol] = globalTileB[(warpID*8 + laneID/4)*K/8 + k + laneID%4];

// With

cp_async(As[storeRow] + storeCol, globalTileA[(warpID*8 + laneID/4)*K/8 + k + laneID%4]);

cp_async(Bs[storeRow] + storeCol, globalTileB[(warpID*8 + laneID/4)*K/8 + k + laneID%4]);

asm volatile("cp.async.commit_group;\n" ::);

The cp.async.commit_group instruction groups these copies together in a cp.async-group which can later be waited on using cp.async.wait_group.

We now use cp.async to set up an n-stage pipeline from global to shared memory. We create circular buffers of size N_STAGES for A and B in shared memory. Before the main loop of the kernel we preload the first N_STAGES - 1 stages into these shared memory buffers using cp.async:

__shared__ uint4 As[N_STAGES*32][8];

__shared__ uint4 Bs[N_STAGES*32][8];

// PRELUDE: load first (N_STAGES - 1) into shared memory

for (int nStage=0; nStage < N_STAGES - 1; nStage++) {

int kStart = nStage * 4;

aStorePtr = As + 32 * nStage;

bStorePtr = Bs + 32 * nStage;

cp_async(aStorePtr[storeRow] + storeCol, aGlobalAddress + kStart);

cp_async(bStorePtr[storeRow] + storeCol, bGlobalAddress + kStart);

asm volatile("cp.async.commit_group;\n" ::);

}

At the start of the main loop there are at most N_STAGES-1 cp.async operations pending, this is an invariant that will be maintained at each loop iteration. We initialize shared memory load and store pointers to stages 0 and N_STAGES-1 respectively and then wait for the first copy to complete, i.e. until there are at most N_STAGES-2 cp.async operations pending. Note that a __syncthreads is required after wait_group as wait_group just synchronizes copy operations within each thread, not across threads.

// MAIN LOOP OVER K BLOCKS

for (int nStage=0; nStage < K/32; nStage++) {

int kStart = (N_STAGES-1+nStage) * 4;

aStorePtr = As + 32 * ((nStage + N_STAGES-1) % N_STAGES);

bStorePtr = Bs + 32 * ((nStage + N_STAGES-1) % N_STAGES);

aLoadPtr = As + 32 * (nStage % N_STAGES);

bLoadPtr = Bs + 32 * (nStage % N_STAGES);

asm volatile("cp.async.wait_group %0;\n" :: "n"(N_STAGES-2));

__syncthreads();

// Preload the fragments for k=0..1, k=2..3 for both A/B tiles

for (int m=0; m<2; m++) {

load_matrix_x4(aReg[m] , aLoadPtr[m*8 + warpOffsetA + loadRowA] + loadColA);

load_matrix_x4(aReg[m] + 4, aLoadPtr[m*8 + warpOffsetA + loadRowA] + (loadColA^2));

}

for (int n=0; n<2; n++) {

load_matrix_x2(bReg[n] , bLoadPtr[n*4 + warpOffsetB + loadRowB] + loadColB);

load_matrix_x2(bReg[n]+ 2, bLoadPtr[n*4 + warpOffsetB + loadRowB] + (loadColB^2));

}

// Start next cp.async: on last N_STAGES-1 iterations the results of

// these copies are not used. The copies are done solely to allow

// us to keep the argument to `wait_group` fixed at N_STAGES-2

kStart = (kStart > 512-4) ? 512-4 : kStart;

cp_async(aStorePtr[storeRow] + storeCol, aGlobalAddress + kStart);

cp_async(bStorePtr[storeRow] + storeCol, bGlobalAddress + kStart);

asm volatile("cp.async.commit_group;\n" ::);

// Compute the mmas

for (int m=0; m<2; m++) {

for (int n=0; n<2; n++) {

mma_m16n8k16(aReg[m] , bReg[n] , dReg[m][n]);

mma_m16n8k16(aReg[m] + 4, bReg[n] + 2, dReg[m][n]);

}

}

}

Next we load the current shared memory stage to registers. In this kernel we preload the entire (M/N=64, K=4) tile into registers, requiring 16 registers for A and 8 for B. The extra shared memory required by the N_STAGES shared memory buffers is the occupancy bottleneck so using these extra registers makes sense to parallelize the loads as much as possible. After the starting the loads to registers, we submit the next cp.async instruction, and finally we perform the mma instructions and increment the load and store pointers modulo N_STAGES.

As N_STAGES-1 K blocks were loaded before the main loop, on the last N_STAGES-1 iterations through the main loop we don’t need to load any more data from global memory. However the argument to cp.async.wait_group needs to be a compile time constant and submitting superfluous copies is a hacky way to keep the argument to wait_group fixed at N_STAGES-2. Without these copies the kernel would be incorrect unless we decreased this argument on each of the last N_STAGES-1 iterations.

Performance

Sadly after all that effort Kernel 3.0 is a very minor improvement over Kernel 2.1. For N_STAGES=3, the execution time is 1000 us, giving 137.4 TFLOP/s, 89.5% cuBLAS, 83.2% 4090 peak performance. Setting N_STAGES=4 has similar performance and higher than this reduces performance. Looking at the warp state stats shows that overall stalls are lower than in Kernel 2.1:

This is partially due to reduced occupancy: Kernel 2.1 has 32 warps per SM while Kernel 3.0 has 24 due to the extra shared memory requirements.

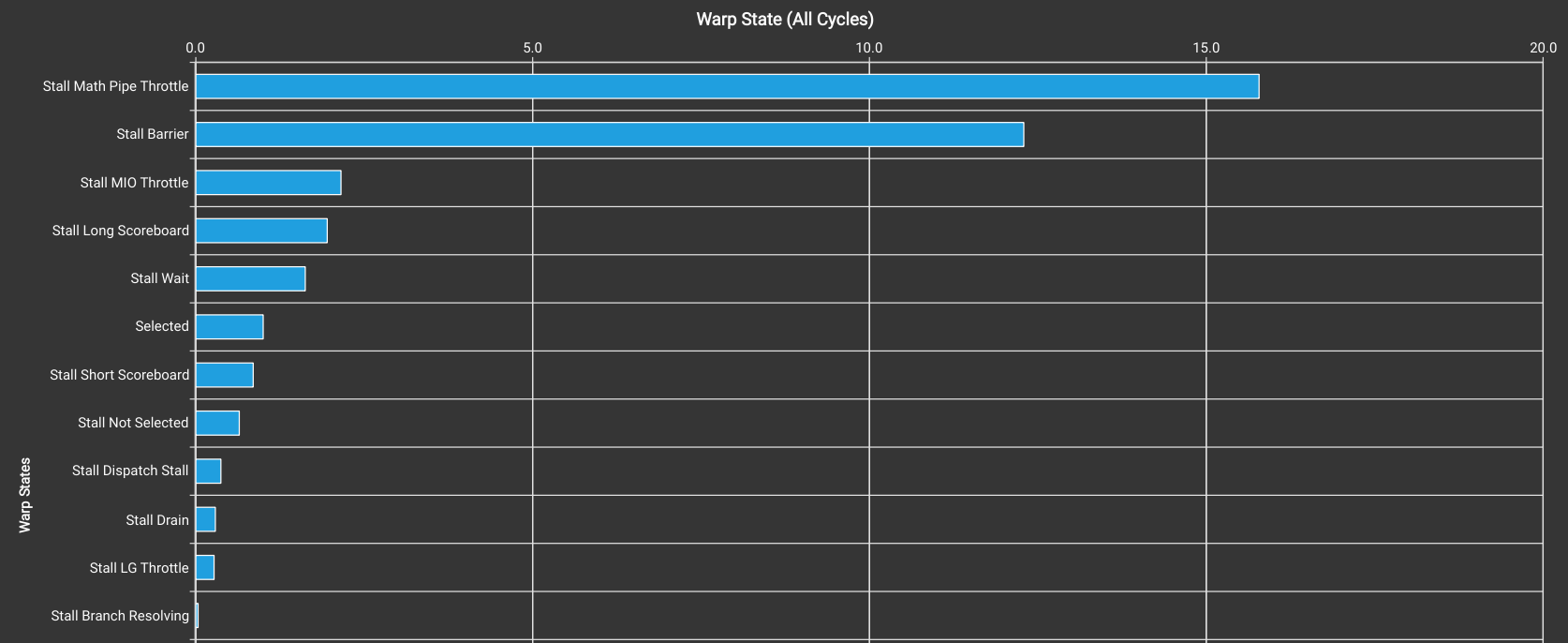

As stalls due to barrier synchronization are still high, a reasonable optimization is to try increasing the work each warp does within a main loop iteration. We do this in Kernel 3.1 by increasing the tiling in the M/N dimensions from 2 to 4. This doubles the thread block tile size to (M/N=128, K=4) meaning that each warp performs 4x4x2=32 mma instructions per main loop iteration.

Kernel 3.1 has an execution time of 895 us, giving throughput of 153.6 TFLOP/s, 100% cuBLAS, 93.0% of RTX 4090 peak performance. Looking at the warp state stats shows that the vast majority of stalls are now due to waiting for Tensor Cores, in fact each warp now waits on average 36 cycles for a Tenor Core to be available:

The ratio of elapsed cycles to mma instructions for Kernel 3.1 is 34.2, consistent with the figure of 93.5% peak performance.

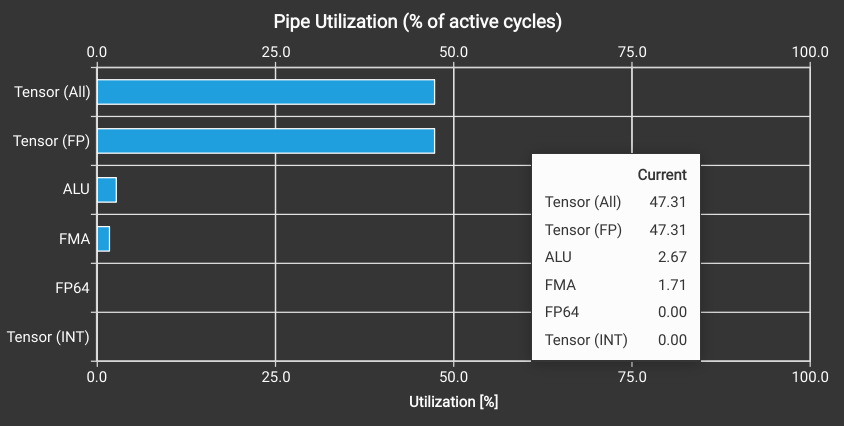

Surprisingly nsight-compute shows the Tensor Core utilization as only 47.3% so what is going on?

It seems that nsight uses a fixed latency of 16 cycles when computing smsp__pipe_tensor_op_hmma_cycles_active as the metric value is consistently 16 times the value of smsp__inst_executed_pipe_tensor_op_hmma. This seems to be an error as the latency for the m16n8k16 mma instruction should be 32, so the utilization should be 94.6%.

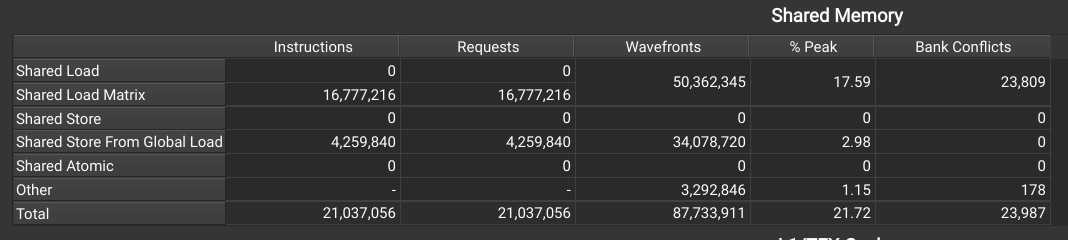

One final thing I noticed is that both Kernels 3.0 & 3.1 have bank conflicts, for 3.1 nsight shows:

Confusingly in this view (Memory Tables) the conflicts appear only in the shared loads, whereas in the source metrics they appear both when copying from global to shared and when loading from shared to registers. The shared loads in particular use the same ldmatrix instruction as in Kernel 2, so I’m not sure how moving to cp.async introduces a conflict there.

It’s possible these conflicts are not real, nsight-compute reports erroneous conflicts in some cases as described here. I need to look into this further and will update the post if/when I find out what’s going on.

Conclusion

We’ve gone from a naive implementation with correspondingly poor performance, to a kernel that is on par with cuBLAS, at least for this extremely specific problem formulation. In the process we’ve developed an understanding of mma and related PTX instructions, along with the techniques needed to feed data to Tensor Cores efficiently.

Code

The code for all Kernels is available here: https://github.com/spatters/mma-matmul.

Appendix: Floating Point Accuracy

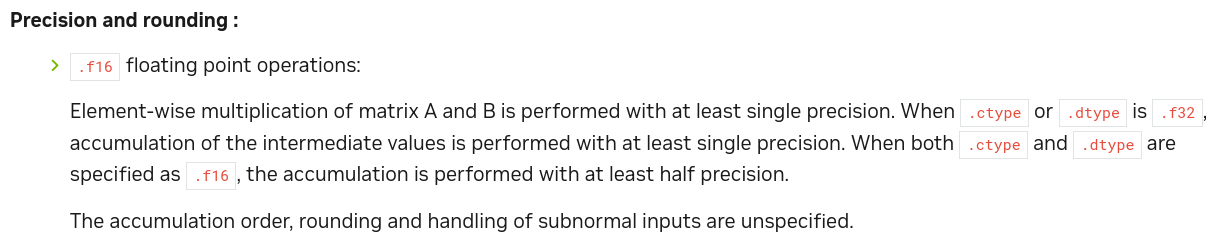

NVIDIA does not fully document the exact numerical behavior of the Tensor Core mma instruction. The PTX ISA states:

Getting into these details is not the focus of this post, but one example of rounding error is worth noting. Kernel 1.0 accumulates the results of the main loop over K directly in

Getting into these details is not the focus of this post, but one example of rounding error is worth noting. Kernel 1.0 accumulates the results of the main loop over K directly in dReg meaning at each iteration the accumulation dReg = dReg + aReg * bReg happens within the mma operation, which can cause loss of precision if dReg is large compared to aReg * bReg.

When testing correctness of the implementation I initialize inputs with U[0,1) values. This means dReg grows monotonically as we loop over K, and performing the accumulation directly in the mma operation causes round off such that the result using mma is consistently lower than a reference implementation using fp16/fp32 operations on CUDA cores (relative difference around 1e-5). This issue can be avoided by instead performing an mma without accumulation, and accumulating the results outside, i.e.

float4 dRegAcc = 0;

float cReg[4] = {0.};

mma_m16n8k16(aPtr, bPtr, cReg, dReg);

float4 *dRegPtr = reinterpret_cast<float4 *>(dReg);

dRegAcc.x += dRegPtr->x;

dRegAcc.y += dRegPtr->y;

dRegAcc.z += dRegPtr->z;

dRegAcc.w += dRegPtr->w;

Applied to Kernel 3.1, this incurs a performance penalty of around 10 us, reduces the difference to the reference kernel by two orders of magnitude and centers it. Detailed investigation into the numerical behavior of Tensor Cores in general can be found in 8.