In fact only the edit tool changed. That’s it.

0x0: The Wrong Question

The conversation right now is almost entirely about which model is best at coding, GPT-5.3 or Opus. Gemini vs whatever dropped this week. This framing is increasingly misleading because it treats the model as the only variable that matters, when in reality one of the bottlenecks is something much more mundane: the harness.

Not only is it where you capture the first impression of the user (is it uncontrollably scrolling, or smooth as butter?), it is also the source of every input token, and the interface between their output and every change made to your workspace.

I maintain a little “hobby harness”, oh-my-pi, a fork of Pi, a wonderful open-source coding agent by Mario Zechner. I’ve so far authored ~1,300 commits, mostly playing around and making incremental improvements here and there when I see a pain point, (or autism strikes and I see an opportunity to embed more Rust via N-API because “spawning rg feels wrong”).

Why bother, you ask? Opus may be a great model, but Claude Code to this day leaks raw JSONL from sub-agent outputs, wasting hundreds of thousands of tokens. I get to say, “fuck it, subagents output structured data now”.

Tool schemas, error messages, state management, everything between “the model knows what to change” and “the issue is resolved.” This is where most failures happen in practice.

Being model agnostic, it is a great testing ground, as the model is but a parameter. The real variable is the harness, where you have unimaginable control over.

Anyhow, let me tell you about this one variable I changed yesterday.

Before I explain what I built, it’s worth understanding the state of the art.

Codex uses apply_patch: It takes a string as input, which is essentially an OpenAI-flavored diff, and instead of relying on a structured schema, the harness just expects this blob to follow a strict set of rules. Since OpenAI folks are without a doubt smart, I’m sure the token selection process is biased to fit this structure at the LLM gateway for the Codex variants of GPT, similar to how other constraints like JSON schemas or required tool calls work.

But give this to any other model, completely unaware of it? Patch failures go through the roof. Grok 4’s patch failure rate in my benchmark was 50.7%, GLM-4.7’s was 46.2%. These aren’t bad models — they just don’t speak the language.

Claude Code (and most others) use str_replace: find the exact old text, swap in the new text. Very simple to think about. But the model must reproduce every character perfectly, including whitespace and indentation. Multiple matches? Rejected. The “String to replace not found in file” error is so common it has its own GitHub issues megathread (+27 other issues). Not exactly optimal. Gemini does essentially the same thing plus some fuzzy whitespace matching.

Cursor trained a separate neural network: a fine-tuned 70B model whose entire job is to take a draft edit and merge it into the file correctly. The harness problem is so hard that one of the most well-funded AI companies decided to throw another model at it, and even then they mention in their own blog post that “fully rewriting the full file outperforms aider-like diffs for files under 400 lines.”

Aider’s own benchmarks show that format choice alone swung GPT-4 Turbo from 26% to 59%, but GPT-3.5 scored only 19% with the same format because it couldn’t reliably produce valid diffs. The format matters as much as the model.

The Diff-XYZ benchmark from JetBrains confirmed it systematically: no single edit format dominates across models and use cases. EDIT-Bench found that only one model achieves over 60% pass@1 on realistic editing tasks.

As you can see, there is no real consensus on the “best solution” to the simple “how do you change things” problem. My 5c: none of these tools give the model a stable, verifiable identifier for the lines it wants to change without wasting tremendous amounts of context and depending on perfect recall. They all rely on the model reproducing content it already saw. When it can’t — and it often can’t — the user blames the model.

0x2: Hashline!

Now bear with me here. What if, when the model reads a file, or greps for something, every line comes back tagged with a 2-3 character content hash:

11:a3|function hello() {

22:f1| return "world";

33:0e|}When the model edits, it references those tags — “replace line 2:f1, replace range 1:a3 through 3:0e, insert after 3:0e.” If the file changed since the last read, the hashes (optimistically) won’t match and the edit is rejected before anything gets corrupted.

If they can recall a pseudo-random tag, chances are, they know what they’re editing. The model then wouldn’t need to reproduce old content, or god forbid whitespace, to demonstrate a trusted “anchor” to express its changes off of.

0x3: The Benchmark

Since my primary concern was about real-world performance, the fixtures are generated as follows:

- Take a random file from the React codebase.

- Introduce mutations, framed as bugs, via an edit whose inverse we can expect (e.g. operator swaps, boolean flips, off-by-one errors, optional chains removed, identifiers renamed).

- Generate a description of the issue in plain English.

An average task description looks something like this:

1# Fix the bug in `useCommitFilteringAndNavigation.js`

2

3A guard clause (early return) was removed.

4The issue is in the `useCommitFilteringAndNavigation` function.

5Restore the missing guard clause (if statement with early return).Naturally, we don’t expect 100% success rate here, since the model can come up with a unique solution that isn’t necessarily the exact same file, but the bugs are mechanical enough that most of the time, the fix is our mutation being reverted.

3 runs per task, 180 tasks per run. Fresh agent session each time, four tools (read, edit, write). We simply give it a temporary workspace, pass the prompt, and once the agent stops, we compare against the original file before and after formatting.

Sixteen models, three edit tools, and the outcome is unambiguous: patch is the worst format for nearly every model, hashline matches or beats replace for most, and the weakest models gain the most. Grok Code Fast 1 went from 6.7% to 68.3%, a tenfold improvement, because patch was failing so catastrophically that the model’s actual coding ability was almost completely hidden behind mechanical edit failures. MiniMax more than doubled. Grok 4 Fast’s output tokens dropped 61% because it stopped burning tokens on retry loops.

0x4: So What?

+8% improvement in the success rate of Gemini is bigger than most model upgrades deliver, and it cost zero training compute. Just a little experimenting (and ~$300 spent benchmarking).

Often the model isn’t flaky at understanding the task. It’s flaky at expressing itself. You’re blaming the pilot for the landing gear.

0x5: Little Bit About the Vendors

Anthropic recently blocked OpenCode, a massively popular open-source coding agent, from accessing Claude through Claude Code subscriptions.

Anthropic’s position “OpenCode reverse-engineered a private API” is fair on its face. Their infrastructure, their rules. But look at what the action signals:

Don’t build harnesses. Use ours.

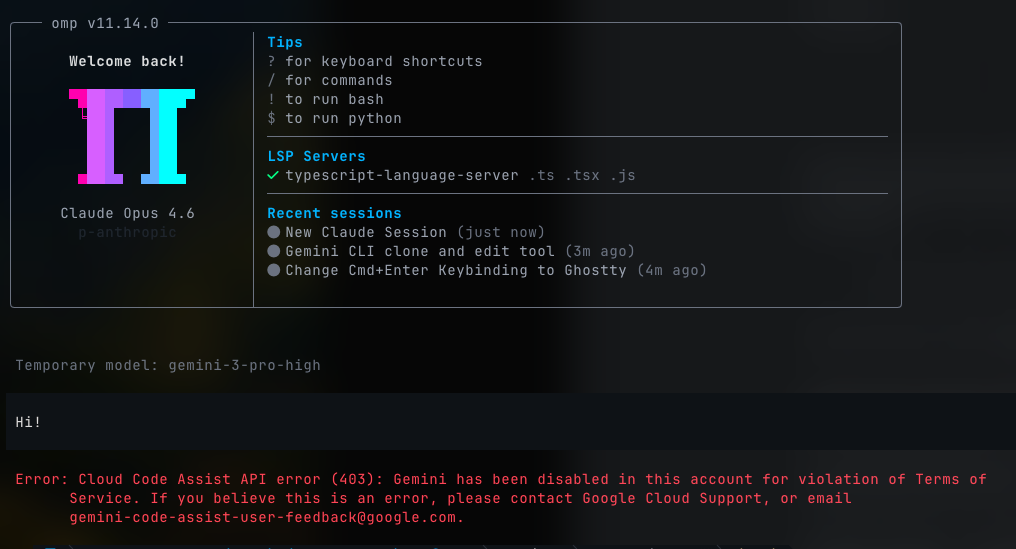

It’s not just Anthropic either. While writing this article, Google banned my account from Gemini entirely:

Not rate-limited. Not warned. Disabled. For running a benchmark — the same one that showed Gemini 3 Flash hitting 78.3% with a novel technique that beats their best attempt at it by 5.0 pp. I don’t even know what for.

Here is why that is backwards. I just showed that a different edit format improves their own models by 5 to 14 points while cutting output tokens by ~20%. That’s not a threat. It’s free R&D.

No vendor will do harness optimization for competitors’ models. Anthropic won’t tune for Grok. xAI won’t tune for Gemini. OpenAI won’t tune for Claude. But an open-source harness tunes for all of them, because contributors use different models and fix the failures they personally encounter.

The model is the moat. The harness is the bridge. Burning bridges just means fewer people bother to cross. Treating harnesses as solved, or even inconsequential, is very short-sighted.

I come from a background of game security. Cheaters are hugely destructive to the ecosystem. Sure, they get banned, chased, sued, but a well-known secret is that eventually the security team asks, “Cool! Want to show us how you got around that?”, and they join the defense.

The correct response when someone messes with your API, and manages to gather a significant following using their tools is “tell us more”, not “let’s blanket-ban them in thousands; plz beg in DMs if you want it reversed tho.”

The harness problem is real, measurable, and it’s the highest-leverage place to innovate right now. The gap between “cool demo” and “reliable tool” isn’t model magic. It’s careful, rather boring, empirical engineering at the tool boundary.

The harness problem will be solved. The question is whether it gets solved by one company, in private, for one model, or by a community, in the open, for all of them.

The benchmark results speak for themselves.

All code, benchmarks, and per-run reports: oh-my-pi