Dec 19, 2025

In addition to the VGA donut, I submitted two other entries in the Tiny Tapeout 8 demo competition, where you submit a "tiny" ASIC design (room for about 4000 logic gates) that outputs 2-bit RGB to a VGA port and 1-bit audio to a speaker. One was a an old school C64/Amiga intro type of thing, and the other was a nyan cat.

Click to play -- video loops imperfectly but the hardware loop is seamless

The intro features a background starfield, a panning 3D checkerboard with colorful tiles, and wavy scrolling text which casts a shadow onto the checkerboard. I was inspired by lft's first AVR demo Craft to add a little cyan oscilloscope to the side of the screen as well.

The size limit was two Tiny Tapeout "tiles" which is not a lot of space for music, effects, and data; this is a very constrained platform for a demo: you get no ROM, no RAM, and every bit of state is a flipflop which takes up a decent chunk of space compared to combinational logic. Traditional "sizecoding" tricks don't apply here -- data compression doesn't help you if you can't actually store a ROM; you have no frame buffer so you must produce a pixel every clock cycle. There's no CPU to exploit, just your own state machine.

Prototyping

Like the VGA donut, this one used the weird custom video mode of 1220x480 and a 48MHz clock as it was easiest to prototype with given the only FPGA hardware I had on hand, but in retrospect I very much regret using this video mode. Most of the digital captures of the demo look bad thanks to dithering and aliasing artifacts. It does look great on a real CRT though!

The above video was made with a Verilator simulation, which compiles the Verilog source down to C++ and allowed me to do cycle-by-cycle simulation of the design, rendering to a SDL window / audio stream. This also allowed me to dump out simulated frames to create the above video. I would later use this SDL VGA verilator testbench for the other projects.

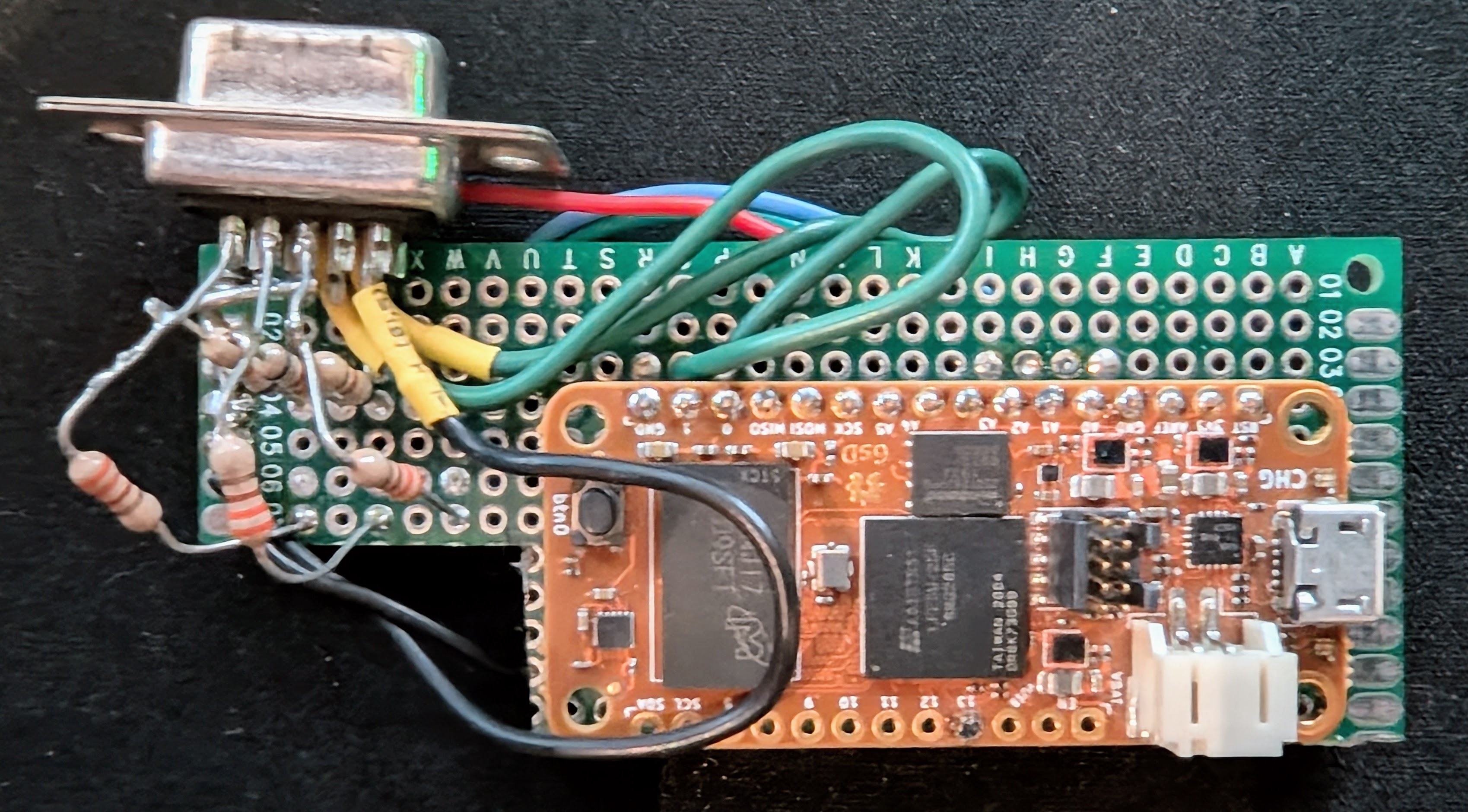

The C++ simulation runs about half-realtime on my system, though, and most of the time I synthesized it for the OrangeCrab's Lattice ECP5 FPGA strapped to an ugly R-2R DAC (it's two bits per channel, so literally R and 2R, no ladder, for RGB) hacked together on a perfboard.

orangecrab FPGA and my RGB222 VGA connector

Sound is output on a single pin through an RC filter; most people used PWM of some kind, but I implemented sigma-delta conversion which is actually simpler (with some tradeoffs; more below). The little solder blob on pin 13 of the orangecrab is where I soldered an audio cable and plugged it into a portable guitar amp for sound.

To get some more color fidelity out of RGB222, I used the same ordered dithering code as in the donut.

Synthesizing for Skywater 130nm

Tiny Tapeout provides a basic workflow for taking your Verilog design and "hardening it" -- laying out the GDS file (which is what goes to the fab) -- as a GitHub action on commit, but there's also a local hardening tool which was absolutely necessary as I alternately added elements to the demo and optimized it to fit. Either there would be too many cells to fit the area, or they would fit but routing wires between them would fail (sometimes after an hour or more!). Being able to dry run several experiments on my own PC was invaluable.

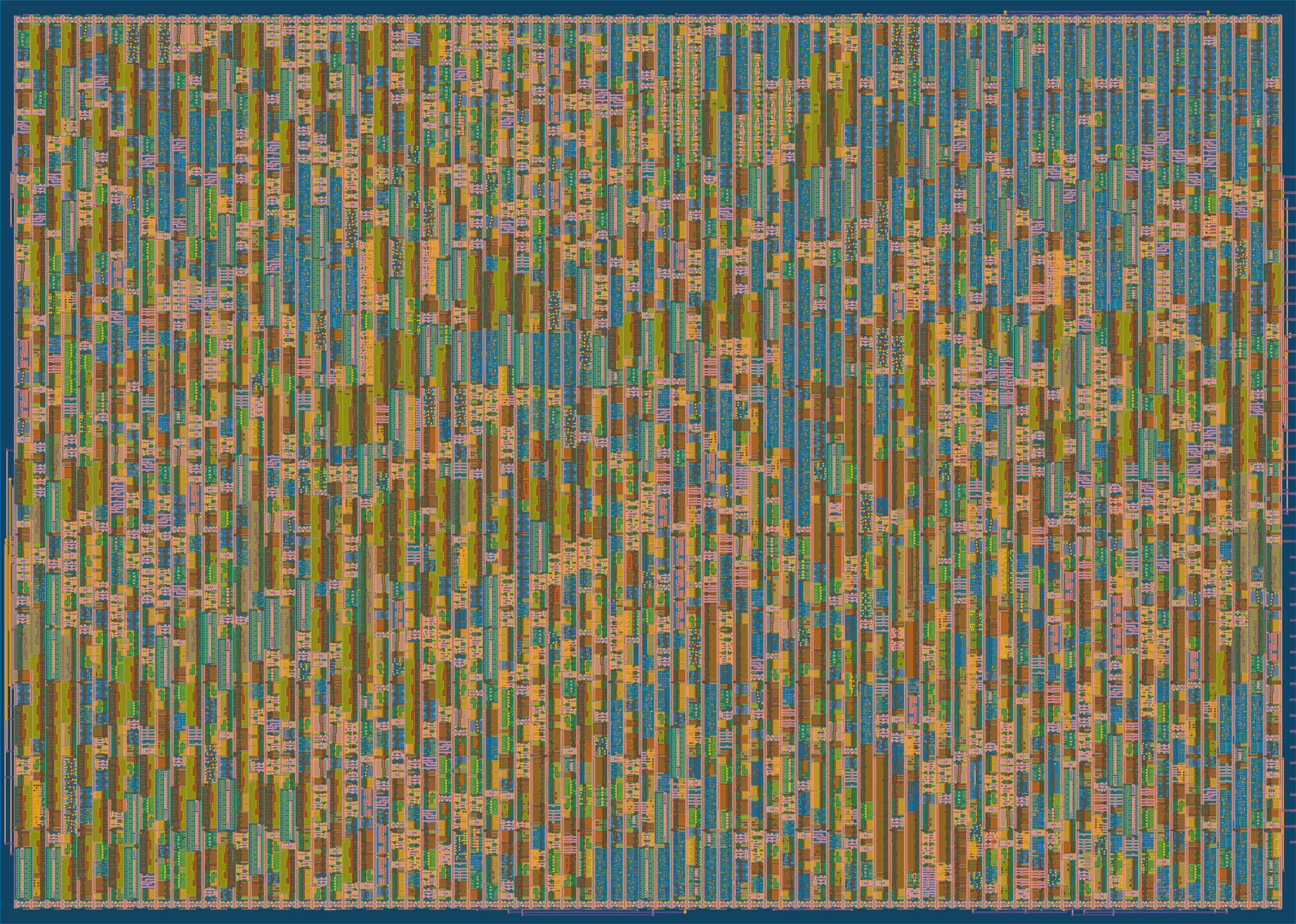

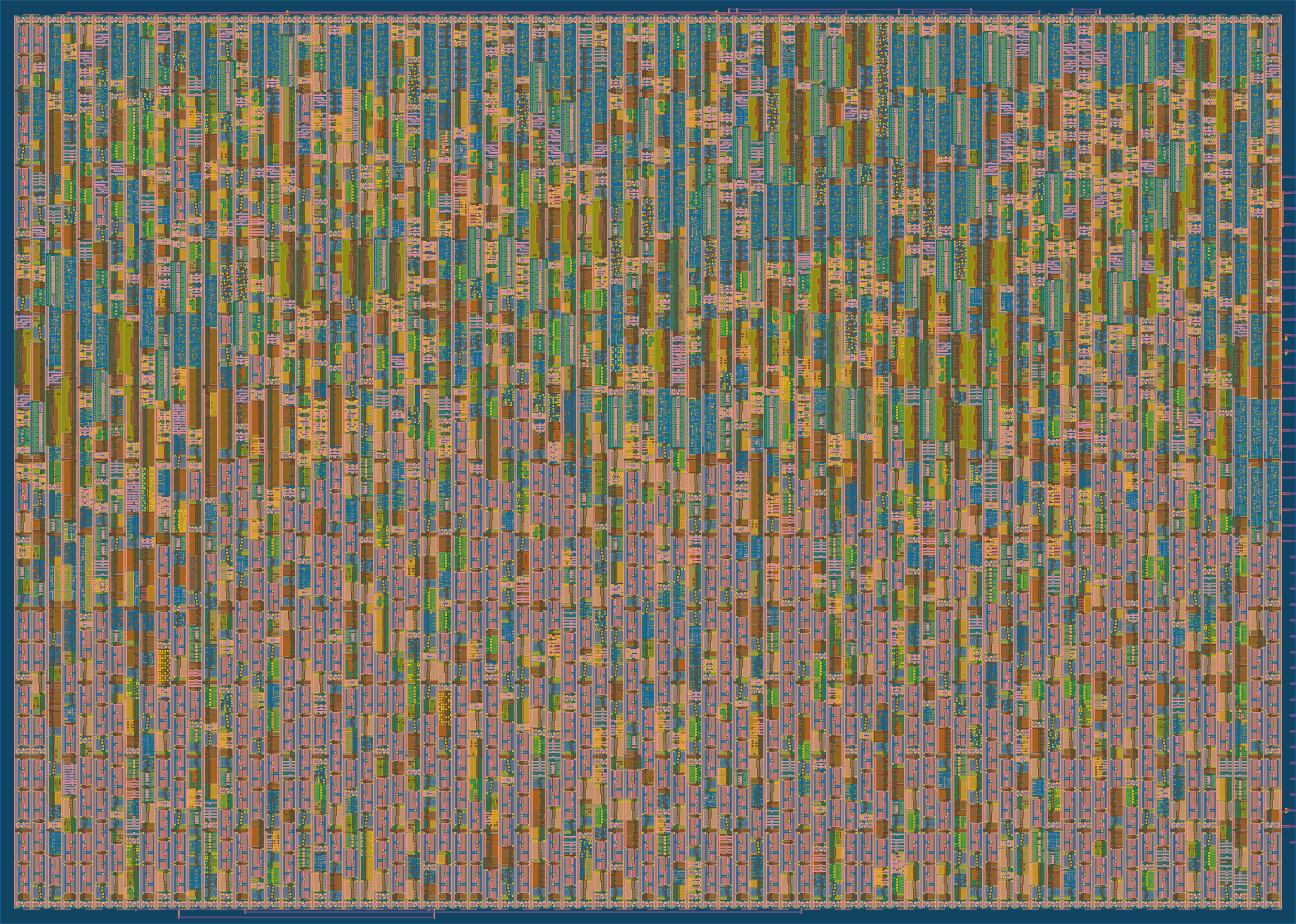

This design ended up using 3374 total cells (breakdown of cell use and 3D

viewer here)

and filling just about every square nanometer. The sort of largish bluish areas

are mostly flip-flops, each representing a bit of state held by the circuit.

Flip-flops are relatively big, so minimizing state bits turned out to be

essential. I still ended up with 293 total flipflops.

This design ended up using 3374 total cells (breakdown of cell use and 3D

viewer here)

and filling just about every square nanometer. The sort of largish bluish areas

are mostly flip-flops, each representing a bit of state held by the circuit.

Flip-flops are relatively big, so minimizing state bits turned out to be

essential. I still ended up with 293 total flipflops.

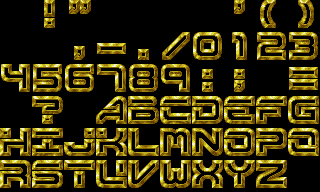

The invitation intro (which is not a real ASIC demo, just a mockup!) that Matt Venn created for the competition inspired me to do something in a similar vein, and for some reason, I was fixated on using one of the fonts for my demo. Encoding text in this font cost a ton of gate area, and so everything else was highly constrained -- eventually I had to give up encoding the color values in the font (but I kept the palette) and go for a generic diagonal striped pattern.

the font used in the demo, from a large collection of ripped demo fonts

Encoding data in an ASIC

You can think of a ROM as a circuit that has a huge truth table -- address 0000000 yields some value, 0000001 another value, etc. Usually this is laid out in a big grid on a chip with some address decoders doing rows and colums and a transistor for each bit encoding high or low values.

Sometimes these are encoded as Programmable Logic Arrays (PLAs) instead of a fully laid out matrix of bits; one example of this is at the heart of the famous Pentium FDIV bug which Ken Shirrif breaks down nicely here.

But you could also just encode the ROM as a bunch of logic gates specific to the pattern of bits specified, e.g., maybe if address bit 7 is on, the result is always 0. In fact part of what the synthesis pipeline does is to take an arbitrarily large truth table and match it to the set of available logic cells (on an FPGA this tends to be a bunch of 4-input lookup tables but Sky130 has all kinds of assorted gates and combined logic cells - random example). So I provided a giant lookup table as a hex file and the yosys synthesis pipeline figured out a way to implement it with the standard cell library, effectively by finding patterns in the data that match up with patterns in the addresses, and then, instead of fitting them in a nice rectangle, sprayed those standard logic cells all over my available die area in whatever shape made sense for the other standard cells connected to them. This makes is very hard to predict how much "data" will fit.

What this means for a limited gate area demo is that instead of minimizing the size of data to store as lookup tables, it's better to limit the algorithmic complexity of the data as a function of its address. Repeating the same power-of-two-sized pattern is free; only variations need extra logic. This is helpful to keep in mind when composing music, for example. So encoding "TT08", if the width of a character cell is a power of two, means that second copy of 'T' is basically free in terms of logic gates.

| a1 | a0 | data |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 'T' |

| 0 | 1 | 'T' |

| 1 | 0 | '0' |

| 1 | 1 | '8' |

a1 == 0 -> 'T' a1 == 1 && a0 == 0 -> '0' a1 == 1 && a0 == 1 -> '8'

drastically simplified example

Sines without sine tables

Usually in a sine scroller you'd expect to see a sine/cosine lookup table, but given the above, it seems wise to avoid it if possible. Just like in my donut demo, I instead rotate a vector on every clock cycle. I don't need random access to the sine table, only \sin(x + o) for each x coordinate on the screen which increments each cycle, with an offset o which increments each frame.

In fact I have a high-resolution sin/cos vector (a_cos, a_sin) that updates

slowly each frame, and a low-resolution one (b_cos, b_sin) initialized from

the high-resolution one at the start of each scanline that updates each clock

cycle.

Cutting bits out of the per-pixel sine generator was one of many hacks done late in development to save on area (remember: flip-flops are pretty large so they had to be trimmed aggressively), and there is visible jankiness in the sine scroller as a result, if you watch closely.

This is the symplectic integrator which generates a perfect circle slightly off-center in just a few simple shift/add operations, first described by Minsky in HAKMEM 149.

reg signed [14:0] a_cos; reg signed [14:0] a_sin; reg signed [11:0] b_cos; reg signed [11:0] b_sin; // on reset: a_cos <= 15'h2000; a_sin <= 15'h0000; // on new frame: wire signed [14:0] acos1 = a_cos - (a_sin >>> 6); wire signed [14:0] asin1 = a_sin + (acos1 >>> 6); a_cos <= acos1; a_sin <= asin1; // on new line: b_cos <= a_cos >>> 3; b_sin <= a_sin >>> 3; // else on each clock: wire signed [11:0] bcos1 = b_cos - (b_sin >>> 7); wire signed [11:0] bsin1 = b_sin + (bcos1 >>> 7); b_cos <= bcos1; b_sin <= bsin1;

Excerpt of Verilog code for generating the horizontal sine offset

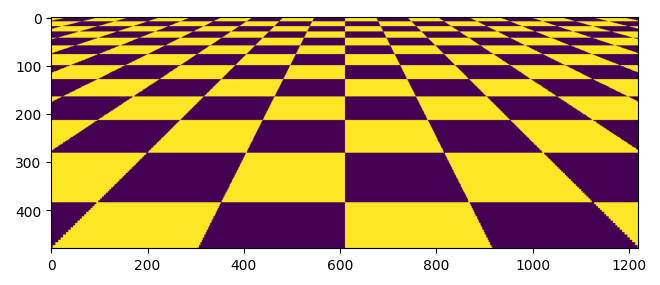

Plane checkerboard

To do the checkerboard, I do a perspective transform of the screen x,y coordinates onto the plane's coordinate system (which I will call u,v). I use the convention that the plane is parallel to the xz-plane at a height of y_p.

I project a ray from the screen until it hits the plane, then recover the u,v coordinate hit. I actually want v and \frac{du}{dx} particularly, as they are constants on each line when looking directly toward the z axis. \frac{du}{dx} gives a fixed value to add to u each clock cycle and I don't need to do any complex math per pixel, and can just multiply that by half the screen width to get u_0 at the left side of the screen.

A ray starts at the origin at t=0 and has 3D coordinates (xt,yt,t), intersecting the plane when yt = y_p for a plane height y_p. Therefore t=\frac{y_p}{y}.

The (u,v) coordinates of the plane are the x and z coordinates at the intersection point, (u,v) = (xt, t) = (\frac{x y_p}{y}, \frac{y_p}{y}). Clearly, \frac{du}{dx} is again just \frac{y_p}{y}, so this expression is the only thing that needs computing.

So I needed to pick an appropriate plane height scale y_p that gives a field of view that looks good and that I can easily divide by y in hardware. I also add an offset y_0 to y to move the camera "down" a bit and also to avoid dividing by 0 (and I don't render the plane when y < y_0 ).

Here's an early mockup in a Jupyter notebook I did working out the math for this, trying to get sensible fixed point value ranges (i.e., number of bits I needed to use in Verilog):

def genboard2(w, h, y0, k): M = (1<<(k+1))-1 y = np.arange(h)+y0 hw = w << (k-2) yx = np.mgrid[:h,:w] dx = (1<<(k-1))//y xl = (-dx*w>>1)&M z = dx print('k', k, 'M', M) print('max dx', dx[0]) print('dx = z =', (1<<(k-1)), '/ y') print('x_left <=', M+1, '-', w//2, '* dx &', M) px = (yx[1].T*dx + xl)>>10 img = px.T.astype(int) ^ z.astype(int)[:, None] return img&32 plt.figure(figsize=(12,3)) plt.imshow(genboard2(1220, 480, 128, 17))

k 17 M 262143

max dx 512

dx = z = 65536 / y

x_left <= 262144 - 610 * dx & 262143

This means we will either need to create a lookup table for each scanline, or actually implement a division algorithm; I tried both, and implementing non-restoring division is smaller.

Sixteen clocks before the end of each scanline, the recip16

module gets a

start signal and begins dividing 65536 by the screen y coordinate. This

yields a fixed point number we can use to scale the u coordinate, and it also

gives the v coordinate.

reg [21:0] plane_u; reg [10:0] plane_du; // latched current du/dx // simplification: the vertical component happens to be // equal to the horizontal step size wire [10:0] plane_v = plane_du; wire [10:0] plane_du_; // output of the divider, next du/dx to load // we can compute this at the end of the previous line during horizontal blank; // we'll latch the output value into plane_du at the start of the line. recip16 plane_dx_div ( .clk(clk48), .start(h_count == H_DISPLAY - 16), .denom(plane_y+1), .recip(plane_du_) ); // when x = 0: // to get plane_u at the left side of the screen, multiply plane_du_ by // -displaywidth/2, implemented here with shifts and adds plane_u <= -((plane_du_<<1) + (plane_du_<<5) + (plane_du_<<6) + (plane_du_<<9)); plane_du <= plane_du_; // else: plane_u <= plane_u + plane_du;

Verilog code generating the u,v coordinates of the checkerboard plane

The checkerboard is created by picking out bits of this (u,v) coordinate frame and XORing them, and the RGB color is some mix of those bits too.

// a_scrollx and y define the plane's checkerboard movement offset wire signed [15:0] a_scrollx = a_cos>>>4; // re-using the per-frame cosine defined above wire signed [15:0] a_scrolly = frame << 3; wire [11:0] hscroll = plane_u[20:9] + a_scrollx[11:0]; wire [10:0] vscroll = plane_v[10:1] + a_scrolly[10:0]; wire checkerboard = hscroll[7] ^ vscroll[6]; wire [5:0] checker_raw_r = checkerboard ? hscroll[8:3] : 0; wire [5:0] checker_raw_g = checkerboard ? vscroll[8:3] : 0; wire [5:0] checker_raw_b = checkerboard ? vscroll[7:2] : 0;

6-bit RGB rainbow checkerboard generator

It's subtle, but the kick drum in the song adds to the plane y_0 offset, so

you can see it "jumping" on every drum hit. And at certain points in the song,

random checkers start lighting up, before finally turning white in diagonal

stripes to the beat, panning the plane_y starting coordinate all the way to

the top of the screen, turning the entire screen white before fading to black

and looping.

Shadows

When drawing the plane, it also renders the scroll text, except using the projected (u,v) coordinates instead of the screen (x,y) so that the shadow of the text is projected onto the plane. However, as I mentioned above, the sine wave is generated by rotating vectors each pixel and so there isn't random access to \sin(u) -- so instead of using the correct scroll height from the projected u, it uses whatever sine is currently available. This shortcut means the shadow isn't really accurate, but it's good enough.

wire shadow_active = char_active && (plane_v is within scrolltext height...); wire [5:0] checker_r = shadow_active ? {2'b0, checker_raw_r[5:2]} : checker_raw_r; wire [5:0] checker_g = shadow_active ? {2'b0, checker_raw_g[5:2]} : checker_raw_g; wire [5:0] checker_b = shadow_active ? {2'b0, checker_raw_b[5:2]} : checker_raw_b;

The shadow mask just shifts the checker color right two bits

Starfield

To do the horizontal scrolling starfield, I essentially needed a constant random number sequence per scanline, so naturally I used an LFSR that resets at the top of the screen and updates at the start of each row; then bits of the LFSR state are used to specify a star's horizontal offset and speed, and then the global frame counter is added on, multiplied by speed. The stars also have longer streaks in time with the snare drum in the music track.

reg [12:0] linelfsr; // on new frame: linelfsr <= 13'h1AFA; // on new scanline: linelfsr <= linelfsr[0] ? (linelfsr>>1) ^ 13'h1159 : linelfsr>>1; // define the x offset of the star on this scanline // bits [12:2] of the LFSR state are the random x offset // bits 1 and 0 boost the movement speed by 2x and 4x wire [10:0] starfield_x = linelfsr[12:2] + (frame<<1) + (linelfsr[1] ? frame<<2 : 0) + (linelfsr[0] ? frame<<3 : 0); // define whether the current pixel (h_count) is actually a star, lengthened by the snare drum timer wire star_pixel = h_count >= starfield_x && h_count < starfield_x + 2 + (7^(audio_snare_frames[3:1])); // stars natually loop off the right side of the screen and re-emerge on the // left side as the starfield_x value overflows

Music

Keeping in mind the constraints on how data is stored, and using some simple music composition ideas, I decided to structure each section of music in an "ABAC" pattern (or ABACABAD). This works well with our logic gate based encoding: The reduced logic will have something like "if measure bit 0 is 0, then use pattern A". And B is just a variation of A, so it can find a lot of redundancies, etc.

Synthesizer

I also needed some very simple-to-code instruments; a square wave arpeggio was a given for this genre of intro, but for percussion I wanted to generate a nice sounding kick drum and I settled on using a triangle wave synthesizer with an exponentially decaying frequency. Then I could multiplex a smooth bassline with the kick drum -- after the kick drum decays, just set the frequency back to the current bassline. For a hihat/snare, add some LFSR noise modulated by an exponential envelope for a hihat/snare kind of sound.

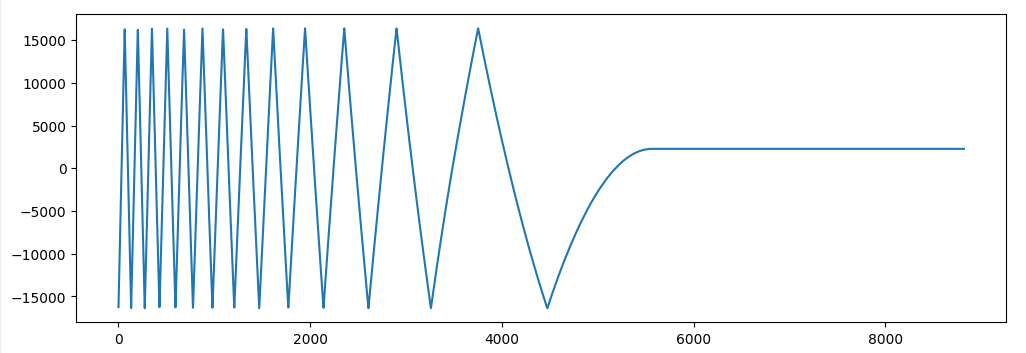

All the instruments were initially mocked up in a Jupyter notebook, as I tried to find efficient ways to generate triangle-based kick drums, etc.

def tri(x): return ((x&65535) ^ (x&32768 and -1 or 0) & 65535) - 16384 def kick(n): osci = 0x3fff # 512*32 - 1 oscp = 0x1235 out = np.zeros(n, np.int16) y1 = 0 for i in range(n): out[i] = tri(oscp>>5) oscp = (oscp + osci)&((1<<21)-1) osci = (osci - ((osci+2047)>>11))&((1<<14)-1) return out plt.figure(figsize=(12,4)) k = kick(4410*2) plt.plot(k) IPython.display.display(IPython.display.Audio(k.astype(np.float32)/127.0, rate=48000))

There are three total channels:

- noise w/ exponential envelope (snare)

- square wave with two-note arpeggio, exponential envelope (chords/melody).

- constant-volume triangle w/ exponential pitch decay (kick)

Exponential envelopes are simply implemented as right-shift counters, where volume 0 is full volume and every few ticks that counter increments, and then the final sample is right shifted by the volume.

As much as possible, I avoided storing state in registers (flipflops are expensive, see above), and tried to make the music driven by a combinatorial logic chain from a simple song position counter. So there is no register for the pulse frequency increment; that's purely derived from the song position. The triangle synth does need one, though, in order to implement the kick exponential.

This led to a lot of off-by-one errors developing the code, as triggers are defined for updating envelopes for the next song position, but the notes for the pulse channel are already set for the current position, etc. Eventually I sorted them all out though it does make the code quite confusing to read, as various counter values differ from the Python version and yet it sounds the same.

A simple trick I found: For the pulse synth, we can also just pick different bits out of the per-sample accmulator to raise the pitch by octaves. I decided to constrain it to a two-octave range.

// note this is signed, so it generates a (+0x4000 or -0x4000) >>> volume wire signed [15:0] pulse_output = {pulse_octave ? pulse_osc_p[12] : pulse_osc_p[13], 1'h1, 14'h0} >>> (2+pulse_vol);

Sigma-delta DAC

Instead of PWM, I did the simplest sigma-delta scheme I could think of:

reg [15:0] sigma_delta_accum; wire [15:0] audio_sample; // assigned by synth wire [16:0] sigma_delta_accum_ = sigma_delta_accum + audio_sample; reg audio_out; // actual output pin always @(posedge clk48) begin sigma_delta_accum <= sigma_delta_accum_[15:0]; audio_out <= sigma_delta_accum_[16]; end

We add the (unsigned) audio sample to the accumulator every clock, and the pin gets the carry. So if the audio sample is at 50% (0x8000), then we get a full clock rate square wave, and if the output sample is 0x0001, we get a constant 0 with a single 1 pulse every 65536 clock cycles and conversely for 0xfffe, we get a constant 1 with a single 0 pulse every 65536 cycles. In general it creates a dense pulse train with no specific period.

The problem with this is that the rising edges and falling edges happen at different speeds on the Tiny Tapeout chip, which introduces a bit of harmonic distortion. I wasn't too worried about harmonic distortion in my triangle/pulse/noise synth.

Composition

I took a lot of inspiration from a C64 SID tune called Crooner by Drax/Vibrants, that then later was adapted for AdLib and I had made an AdLib OPL2 emulator for it. I decided to keep my tune very simple though, so there's no real melody, just the same chord progression as Crooner in a repeating four bar pattern:

| Am | C | D | F G |

The D major isn't really in the Am/C scale (more of a secondary dominant) but

this meant there were a total of eight unique notes in the scale instead of the

usual seven: C D E F F# G A B, giving me a power of two-sized table of base

frequencies. This meant I could have a 3-bit wide table for notes, plus another

bit for octave, so each instrument has a total of 16 possible notes to play.

Using a two-note arpeggio is a departure from conventional three-note arpeggios in most tracked music, but counting to 2 by slicing off a bit from the song tick counter is easier than counting to 3 which would require an extra counter; besides, the bass can play the root note of the chord and the melody can play the thirds and fifths.

I also swung the tempo pretty strongly, swapping between 15 and 25 ticks per beat which really improved the feel.

And then I literally wrote the song as a bunch of strings in Python, just typing out the scale notes and using the # symbol for F#:

snareA = '..x..xx...x..xx.' kickA = 'x...x...x...x...' snareB = '..x...x..xx...x.' kickB = 'x...x..x.x..x...' snareC = '..x...x...x..xxx' kickC = 'x...x..xx...x...' snareD = '..x..xx...x...xx' kickD = '................' # concatenate ABACABAD pattern snare = snareA + snareB + snareA + snareC + snareA + snareB + snareA + snareD kick = kickA + kickB + kickA + kickC + kickA + kickB + kickA + kickD # bassline which repeats throughout entire song # 1+2+3+4+1+2+3+4+1+2+3+4+1+2+3+4+ bass_chart_notes = 'AEAAAEAACCGCECCCDDD#D#DDFCFFGDGG' bass_chart_octs = '01100000000110100011010101100110' # pulse aka square wave # the note and 'arp' note alternate in a rapid arpeggio; oct defines the octave # the envelopes are triggered by a non-blank entry in the note string # A section, basic pulsAnot = 'A...A.....A...A.G...G.....G...G.#...#.....#...#.F...F...G...G...' pulsAoct = '0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000' pulsAarp = 'EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAABBBBBBBB' # B section, slight embellishments pulsBnot = 'C...C.....A...C.G...C....CG...GG##..#.....#...#FFF..FF.FGG..GG..' pulsBoct = '1000100000000000000000000100000001000000000000000100010101000100' pulsBarp = 'EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEGEEEEGCEEEECAAAAAAAAAAAAAAACACAAAAAABDBBBDBB' # C section, melodic finale pulsCnot = 'CCA.CAA..ACACCCAGGCCGCGE..GGG.GG#DD###.#.D###.#DFF.FF.CFGG.GG.GD' pulsCoct = '0000011001100100001000100001001000100100001010011001000001001001' pulsCarp = 'EEEEAEEEEEEEAAECEEEECEECEEEECECEAAADADAAAAADDAAAAACCAAFABBBBDBBB' # ABAC sections concatenated puls_chart_note = pulsAnot + pulsBnot + pulsAnot + pulsCnot puls_chart_oct = pulsAoct + pulsBoct + pulsAoct + pulsCoct puls_chart_arp = pulsAarp + pulsBarp + pulsAarp + pulsCarp

The full Python script emulates all the instruments exactly and plays the entire song, while also dumping out the data tables used by the verilog code.

notefreq: 5b 67 73 7a 81 89 9a ad

pulsmask: 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 1

pulsfreq1: 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 6 6 6 0 0 5 5 5 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 5 5 5 5 5 5 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 0 0 6 6 0 6 6 6 6 6 0 6 0 0 0 6 5 5 0 0 5 0 5 2 2 2 5 5 5 5 5 5 4 1 1 4 4 4 4 4 4 1 4 4 4 4 4 1 3 3 3 3 3 3 0 3 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 1

pulsfreq2: 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 5 5 5 5 5 5 0 0 0 0 2 0 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 0 6 0 0 0 6 6 6 6 7 1 1 1 7 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 2 2 2 2 6 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 6 6 2 0 2 2 2 2 0 2 2 0 0 0 2 2 0 0 0 2 6 6 6 1 6 1 1 6 6 6 6 1 1 1 6 6 6 6 6 0 6 6 3 6 7 7 7 7 1 1 7 7

pulsoct: 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 1

bassfreq: 6 2 6 6 6 2 6 6 0 0 5 0 2 0 0 0 1 1 1 4 1 4 1 1 3 0 3 3 5 1 5 5

bassoct: 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 0

kick: 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

snare: 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1

all data needed to play the song

Retrospective

There are a few design choices I made that I regret after finishing this intro.

First, the audio track has a completely independent clock from the visual component. A lot of classic chiptune music was constrained by using 50Hz or 60Hz frame timers, limiting the available tempo choices. Additionally I didn't want to tie my sample rate to the VGA horizontal frequency (31.5kHz) which would have been a natural choice. Instead I used a 48MHz / 1024 clock divider (46875Hz) and used a tick rate asynchronous from the VGA frequency, and then I could better control tempo, etc.

This seemed like a good idea, except when I tried to do simple music-sync effects. Now at any given point on the screen, the music can tick over, resulting in "tearing". There's a speckly checkerboard effect that's in sync with the music, but it doesn't "pop" because it doesn't actually work correctly. Additionally, the music loops about halfway through the last frame of the intro, resulting in a checkerboard blinking in for half of a frame as some counter overflows before it can be properly reset at the top of the next frame.

The 1220x480 video mode was also a huge mistake. In general, the people who can test this design aren't going to do it on a CRT, so better to just sync up properly with the LCD pixels and not rely on 90s era temporal dithering and CRT smoothing.

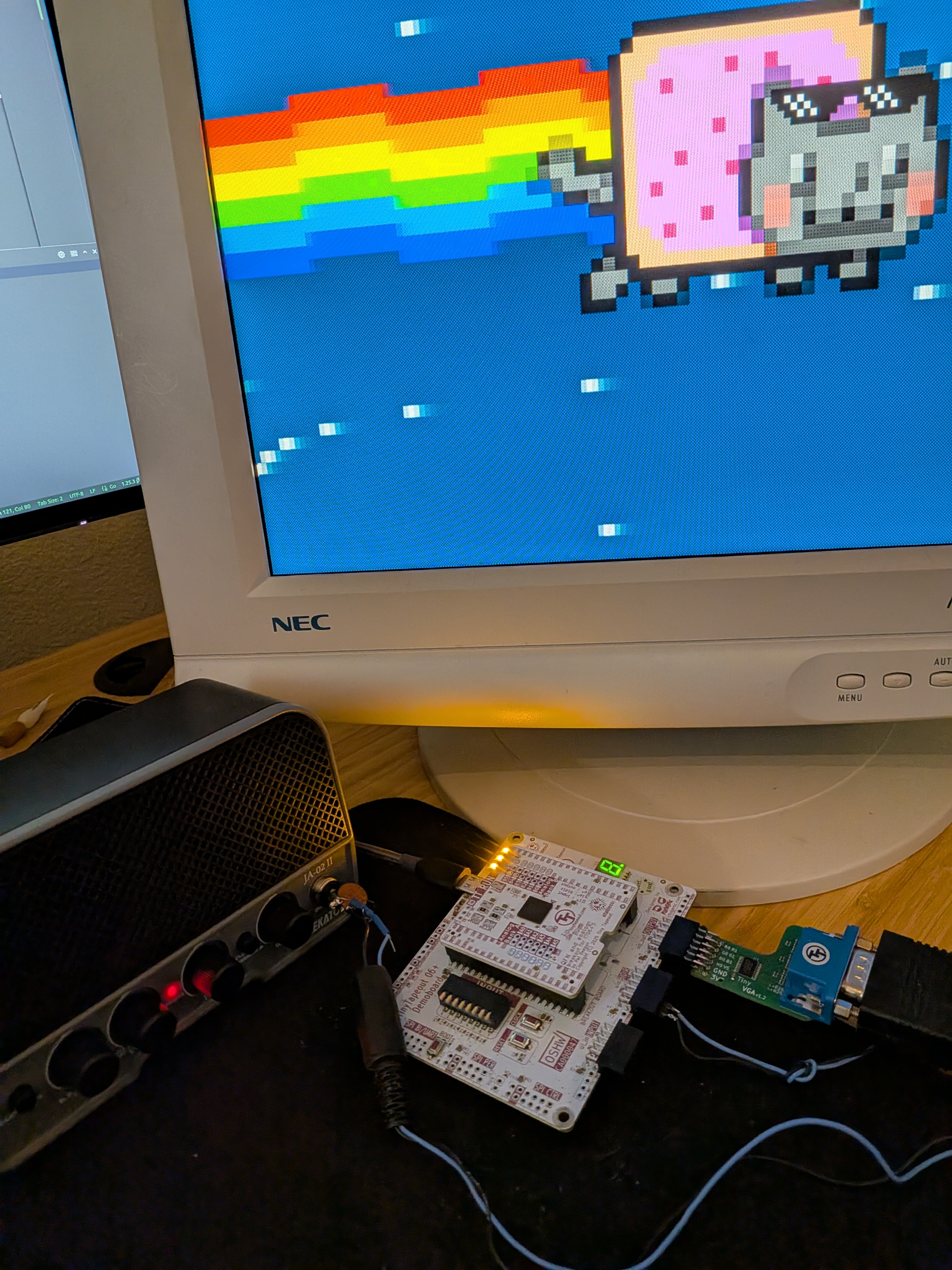

nyan.cat demo; in the actual design the musical intro only plays once, and then loops seamlessly as the sunglasses scroll off the screen.

A couple days before the Tiny Tapeout 8 deadline, Uri threw down a challenge in the Discord to make a Nyan Cat, and so I decided to take everything I learned from making the TT08 intro and the donut and put together a design using ripped art and music. I'd reuse some code, avoid previous mistakes, use 640x480 VGA, audio synced to video (31.5kHz sample rate, 60Hz tempo ticks), simpler dithering. Ideally, get it all to fit in one tile.

Well, it turns out the design I came up with worked and all the cells fit into one tile -- but it was too crowded like that for detailed routing to succeed. Without any workable ideas to cut down on space and without much time left before the deadline, I just grew the design to two tiles and added a "deal with it" sunglasses easter egg to consume some tiny portion of the expanded space.

The layout. The red cells throughout the bottom half are actually just filler capacitors, essentially unused space. Alas, it didn't fit into one tile though.

Art

I started by grabbing the original animated .gif from nyan.cat and wrote a python script to extract the individual frames, the palette, and generate a remapped data table with all of the unique animation frames. I used a color picker to grab all the original rainbow colors and background color, then converted them to their closest match in RGB222 with a 2x2 dithering matrix.

original nyan.cat .gif

The cat smoothly shifts back and forth in the original animation, so I reused the sine wave generator code to give him a little x-offset.

Originally there are little exploding stars/fireworks? scrolling by in the background, but I didn't get around to emulating those. Instead I just reused the LFSR-based starfield from the TT08 demo except without random star speeds. This leads to extremely visible artifacts where the star positions are obviously being right-shifted from one line to the next near the bottom of the screen.

Music

I found a MIDI rendition of the nyan.cat song and wrote yet another crappy Python script to parse the MIDI, split out the melody and bass sections, remap note indices to a minimal scale of notes (once again, only 8 notes are used in the scale), and dump out tables that the Verilog code could read.

Total length: 288 ticks

melodynotes ['C#', 'D ', 'D#', 'E ', 'F#', 'G#', 'A#', 'B ']

bassnotes ['C#', 'D#', 'E ', 'F#', 'G#', 'B ']

Remapped melody scale: ['C#', 'D ', 'D#', 'E ', 'F#', 'G#', 'A#', 'B ']

Number of unique notes after remapping: 8

melody increment table 48 4c 51 56 60 6c 79 81

bassnote 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 2 2 2 2 5 5 5 5 0 0 0 0 4 4 4 4 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 2 2 2 2 5 5 5 5 0 0 0 0 4 4 4 4 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 2 2 2 2 5 5 5 5 0 0 0 0 4 4 4 4 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 2 2 2 2 5 5 5 5 0 0 0 0 4 4 4 4 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 3 3 5 5 7 7 3 3 2 2 4 4 7 7 2 2 0 0 3 3 5 5 7 7 7 7 2 2 4 4 7 7 3 3 5 5 7 7 3 3 2 2 4 4 7 7 2 2 0 0 3 3 5 5 7 7 7 7 2 2 4 4 7 7 3 3 5 5 7 7 3 3 2 2 4 4 7 7 2 2 0 0 3 3 5 5 7 7 7 7 2 2 4 4 7 7 3 3 5 5 7 7 3 3 2 2 4 4 7 7 2 2 0 0 3 3 5 5 7 7 7 7 2 2 4 4 7 7

bassoct 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2

basstrigger 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0

melodynote 2 3 4 4 7 7 2 3 4 7 0 2 0 6 7 7 4 4 2 3 4 4 7 7 0 6 7 0 3 2 3 0 4 4 5 5 2 2 2 7 1 0 7 7 7 7 0 0 1 1 1 0 7 0 2 4 5 2 4 0 2 7 0 7 2 2 4 4 5 2 4 0 2 7 1 2 1 0 7 0 1 1 7 0 2 4 0 2 0 7 0 0 7 7 0 0 4 4 5 5 2 2 2 7 1 0 7 7 7 7 0 0 1 1 1 0 7 0 2 4 5 2 4 0 2 7 0 7 2 2 4 4 5 2 4 0 2 7 1 2 1 0 7 0 1 1 7 0 2 4 0 2 0 7 0 0 7 7 0 0 7 7 4 5 7 7 4 5 7 0 2 7 3 2 3 4 7 7 7 7 4 5 7 4 3 2 0 7 4 2 3 4 7 7 4 5 7 7 4 5 7 7 0 2 7 4 5 4 7 7 7 6 7 4 5 7 3 2 3 4 7 7 6 6 7 7 4 5 7 7 4 5 7 0 2 7 3 2 3 4 7 7 7 7 4 5 7 4 3 2 0 7 4 2 3 4 7 7 4 5 7 7 4 5 7 7 0 2 7 4 5 4 7 7 7 6 7 4 5 7 3 2 3 4 7 7 0 0

melodyoct 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1

melodytrigger 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0

output of the Python script containing the full song data extracted from MIDI

Then for kicks I added the kick drum (ha ha) to the bass track, same as the TT08 intro. I'm pretty sure I just wrote the triggers for that out by hand; there wasn't time to create any fancy tools.

This has just two audio channels:

- Bass/kick, pure square wave this time

- Melody, 25% duty cycle pulse wave to add timbre

Both bass and melody use per-tick exponential decay envelopes, with each tick occurring at the start of a video frame (so 60Hz). The kick drum takes over the bass channel for a few frames, exponentially decreasing its frequency before returning to the original bass pitch/envelope.

All notes use the same increment table, but octaves are shifted by changing the phase bits used. The "sqr" channel is actually 25% duty cycle pulse, turning on only when both of the 2 MSBs are on.

reg [12:0] sqr_pha; reg [5:0] sqr_vol; wire [2:0] cur_melody_note = melody_note[songpos]; wire [7:0] sqr_inc = noteinctable[cur_melody_note]; wire sqr_on = cur_melody_oct == 2 ? sqr_pha[10]&sqr_pha[9] : cur_melody_oct == 1 ? sqr_pha[11]&sqr_pha[10] : sqr_pha[12]&sqr_pha[11]; wire [5:0] sqr_sample = sqr_on ? sqr_vol : 6'd0; // On each beat (6 ticks): if (melody_trigger[songpos_next]) begin sqr_vol <= 63; end // On each non-beat tick: sqr_vol <= sqr_vol - (sqr_vol>>3); // On each audio sample: sqr_pha <= sqr_pha + {4'b0, sqr_inc};

Verilog code generating the pulse channel with envelopes

I also added a global low pass filter because the pulse melody was a bit piercing. This turned out to dull the sound a lot more than I intended, though.

Tiny Tapeout 8 began manufacturing in September 2024, completing production of wafers and dies. And then, in March 2025, we received the devastating news that Efabless, the company supporting Tiny Tapeout, abruptly shut down, leaving its assets, which included mid-production TT08 and TT09 chips, in an uncertain state. TT08 was just being packaged at the time of the shutdown.

This was kind of a crushing blow for me, since I had put so much effort into the designs on this chip in particular. It also meant that the judging for the demo competition was indefinitely on hold, as it required the physical hardware to be delivered to the judges.

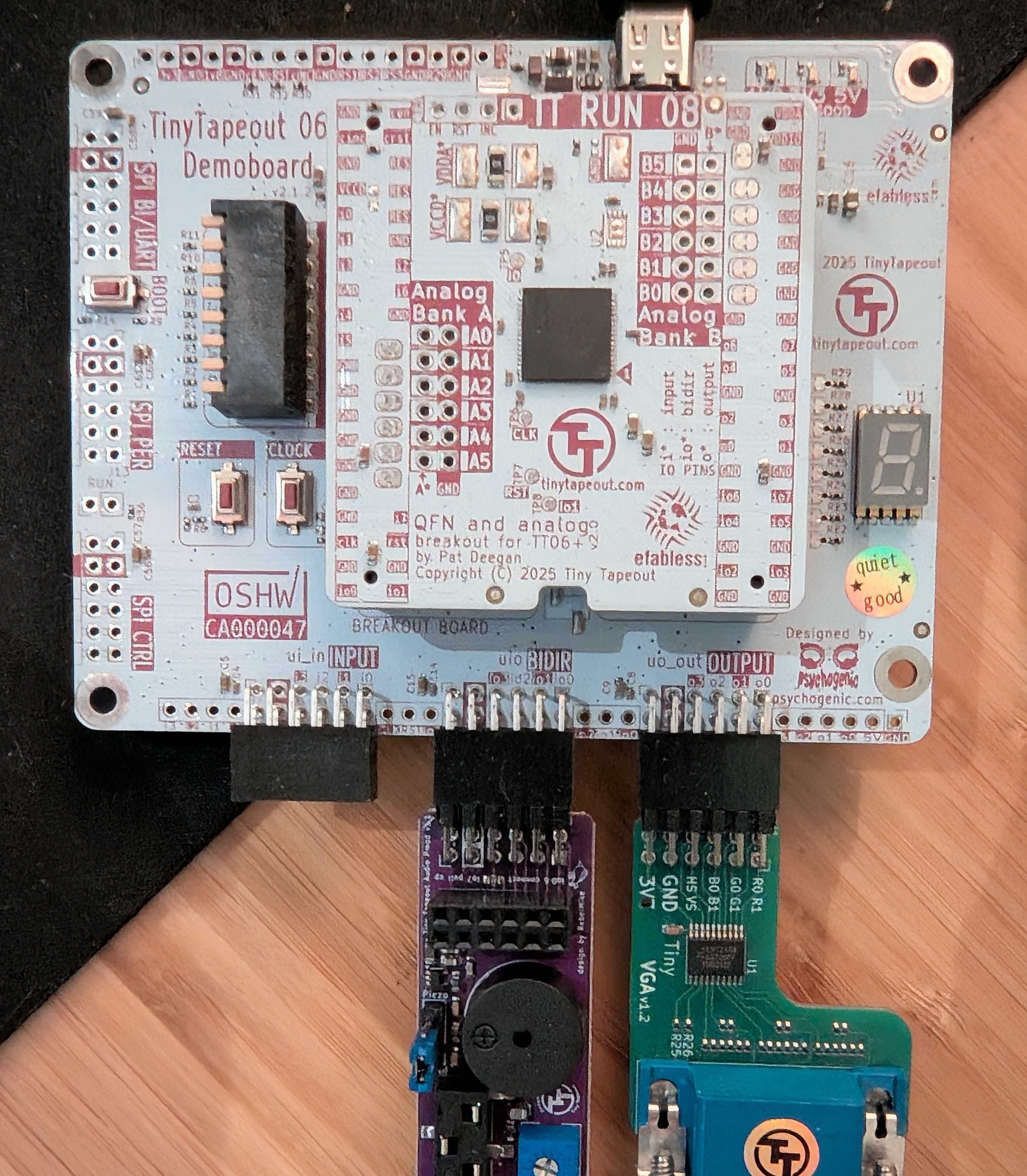

And then, out of nowhere, the #tt08-silicon channel showed up on the

Tiny Tapeout discord server in late September 2025. It seems the chips were

acquired by a new company and turned over to the Tiny Tapeout team. Soon after, this arrived at my doorstep:

Tiny Tapeout 8 development board, with audio and VGA Pmods attached

In fact all of my designs worked perfectly -- except it turns out I had relaxed the timing on the donut a bit in order to reduce gate area (lower clock rates require lower drive strength which means smaller transistors), so the donut needs to run at 45MHz instead of 48MHz to avoid some glitches.

Tiny Tapeout 8 running Nyan Cat on my LCD and a guitar amp for audio

Needless to say, I was elated when I saw my designs running perfectly on my desk after a long year of waiting and expecting the worst.

I was holding out on doing this writeup until the judges had definitively seen the hardware running. bitluni showed them all off on a recent livestream with both LCD and CRTs, so I figured it's finally time to post this.

Revisiting these designs over a year later, I had forgotten how involved they were and how many intricacies I wanted to explain in this post.

I learned so many new low-level tricks building these demos and I have even better tricks in store for the next one.