Note: This is Part 7 in a short series of essays on Understanding Customer Demand. Read Part 6 here.

At the end of last year, we ran a Jobs to be Done (JTBD) interview process with Commoncog members. Much has already been written about the interview method, but I thought it would be useful to describe what we’ve learnt from doing it. This includes things that we struggled with, things we found oddly tricky, and things that we wished someone had told us earlier.

At this point in the Understanding Customer Demand series, you should already know what the JTBD framework is, and how it fits into the arsenal of demand thinking that we’ve covered. This essay is going to be a short one: a field report from practice.

The first thing you’ll discover about the JTBD interview is that it’s really hard to do. I think this is obvious from reading between the lines of all the major JTBD texts: Demand Side Sales 101 from Bob Moesta is filled with sidebars about how things can go wrong with the interview process; the team over at the Re-Wired saw it necessary to release The Jobs to be Done Handbook — a 66 page booklet designed to be skimmed right before an interview — which gives you a hint that the interview process is not as straightforward as it seems.

Why is this so difficult? I think the main reason is that the JTBD is a form of ethnographic interview, and if you’ve never done ethnographic research before, you’d have to pick up the basics as you execute.

If we take a step back, the JTBD interview is actually really simple. It is just a way of getting your customers to tell you the story of how they bought your product.

The problem with it is two-fold. First, most customers can’t remember how they bought your thing. Second, the human mind is not designed for self knowledge. Humans will make up reasons for why they do things, and you have to catch them when they do. Skill at the JTBD interview is about getting better at both things separately.

Of the two, the first problem is easier to solve. The JTBD texts have a list of tricks you can use to get your customer to remember. The most basic one is to never interview a customer who bought too long ago. At Commoncog, we didn’t take this seriously enough, and so we ended up with a bunch of interview transcripts that were useless for our purposes.

In general:

This leads to a counter-intuitive recommendation: at the beginning of your JTBD journey, limit your interviews to customers who have purchased less than six months ago. As you get more skilful, you can increase your filter to customers who have bought a year or so ago. Start with the easy ones, the ones who bought most recently, and then progressively step up the difficulty.

The authors give you a handful of tips for dealing with customers who can’t remember:

All of these tricks help, and I’ve found that you can get quite good at them in just a few interviews.

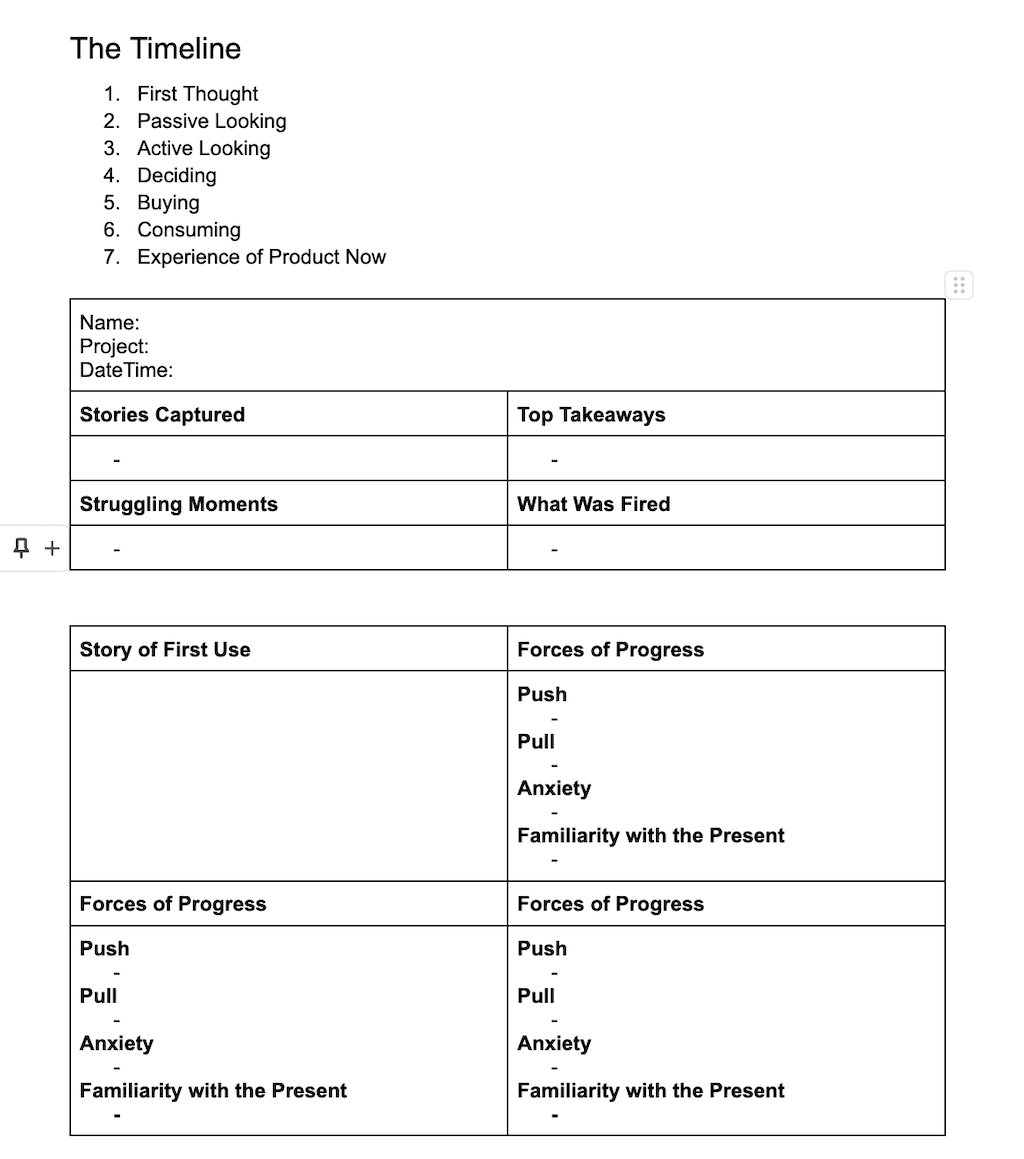

The second problem — that humans are not made for self knowledge — is the harder problem to tackle. At various points in your interviews you’re going to want to slow down and dig into a specific event, in order to isolate one of the triggers on the JTBD timeline. A strong assumption behind the JTBD framework is that “things don’t happen randomly” and “there is causality in human behaviour.” Now, whether or not there is true causality in human behaviour is a matter for deep philosophical debate. But for the specific context of this interview, it is helpful to believe that this is the case, and therefore it is helpful to act as if it were true.

Pushing for causal factors is tricky, because you don’t want to push too hard. Skill at this bit is:

I don’t have a good answer for how to get better at this, beyond “put the reps in, and get feedback from your team.” For instance, early on in our project one of my teammates pointed out that I should have the date of purchase ready before each interview, since Commoncog sold subscriptions and purchase dates were trivially easy for us to track. While listening to my interview recordings, he had noticed that there was often an awkward bit where I would be pulling up the details of their subscription. This was a waste of time. I had already noticed this, but I added that task to my pre-interview checklist immediately after receiving this feedback.

The authors of JTBD have another standard recommendation that I didn’t take seriously, but should’ve: they recommend that you conduct the interview with one other person, as a pair. That is: a team of two interviewers for each interviewee. The reason is that running the JTBD interview is very cognitively demanding, and it helps to have a second brain catch you in case you miss something. Unlike with Sales Safari, if you forget to ask about something in the JTBD interview, it’s likely you’ll have lost that insight forever.

This complicates the interview process, though: it now means that you have to find a partner, schedule them for each and every customer interview, and take the time to debrief, reflect, and improve as a team.

One thing we did do — that is considered best practice amongst JTBD practitioners — is that we ran practice interviews with each other before executing it with our customers. I highly recommend this. Pick a friend or a family member, and then pick a purchase that they made not too long ago. (Make sure the purchase is not a gift, nor an impulse buy — these are two scenarios where the JTBD framework just doesn’t work.)

JTBD interviewing skills do atrophy from lack of practice. In this they are like riding a bike, or playing tennis. It’s a good idea to do practice interviews before every major customer research project. I learnt this the hard way: I ran a JTBD interview a couple of weeks ago, after an eight month break, and found myself horribly rusty.

I’m not making that mistake again.

Unlike Sales Safari, JTBD interview analysis is comparatively easy to do. In Sales Safari, a huge part of the difficulty with the technique is divining intention and psychology based on a free-form interview. With a JTBD interview though, the analysis is almost trivial.

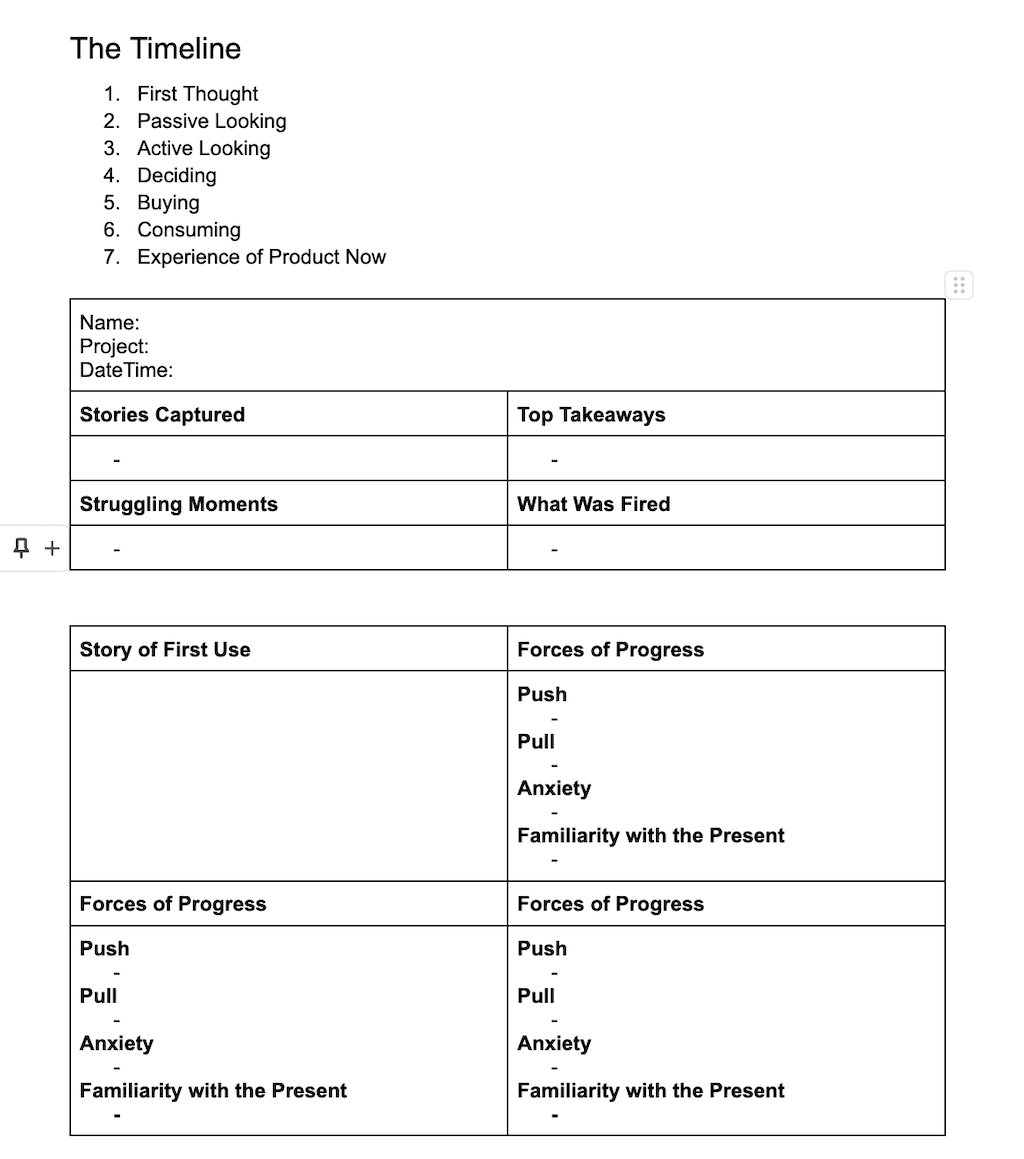

You are expected to fill in the following format:

Recall that the JTBD timeline looks like this:

For each of the points in the timeline, you are expected to jot down the four forces that acted on them in that moment. This is no more difficult than a listening comprehension test — assuming you’ve done the interview correctly.

Unfortunately, if your interview was badly done, you’ll find that you can’t fill in the template. And there’s nothing you can do to salvage it — you’ll end up with a half-empty, partially completed timeline. This is why getting the JTBD interview right is so, so important.

Let’s take a step back, though. It’s worth asking why qualitatively customer analysis is so difficult. At this point in the series, we’ve already taken a look at one such method that I’ve described as exceedingly tiring: Sales Safari. What is true for Sales Safari analysis is still partially applicable to JTBD interview analysis.

Sales Safari is difficult because everything that a customer says has two kinds of informational value:

The most revealing, most valuable bits of any customer research interview lie in the positioning component of what is said, not the actual contents of what is being said. Divining what is unsaid — and why — takes skill. It is exhausting in the same way that empathy is exhausting. In fact, one of the best ways you may evaluate skill at demand is to observe how much positioning value someone is able to extract out of a customer call.

We may get more specific about what positioning value looks like, of course. When you’re listening to an interview, ask:

This is still only half the picture. The other half comes from noticing patterns across customers. Things like “wait, isn’t it odd that five customers have said the exact same thing? What’s going on here?”

Listening for positioning value and analysing for patterns across customers is what makes qualitative customer interviews difficult. JTBD is slightly easier, of course, because it merely focuses on explicating a buyer’s timeline. But to get the most out of this process, you still need to analyse a little for why customers are doing the things they do — and this analysis is where most of the cognitive costs will lie.

It’s worth asking what we learnt at the end of this three month project.

What did our JTBD interviews uncover? We learnt a number of things, but most of those findings will require too much context to understand. Instead, I’ll describe just one finding to you, as an example of how the JTBD framework can be useful — especially when used in combination with a data capability.

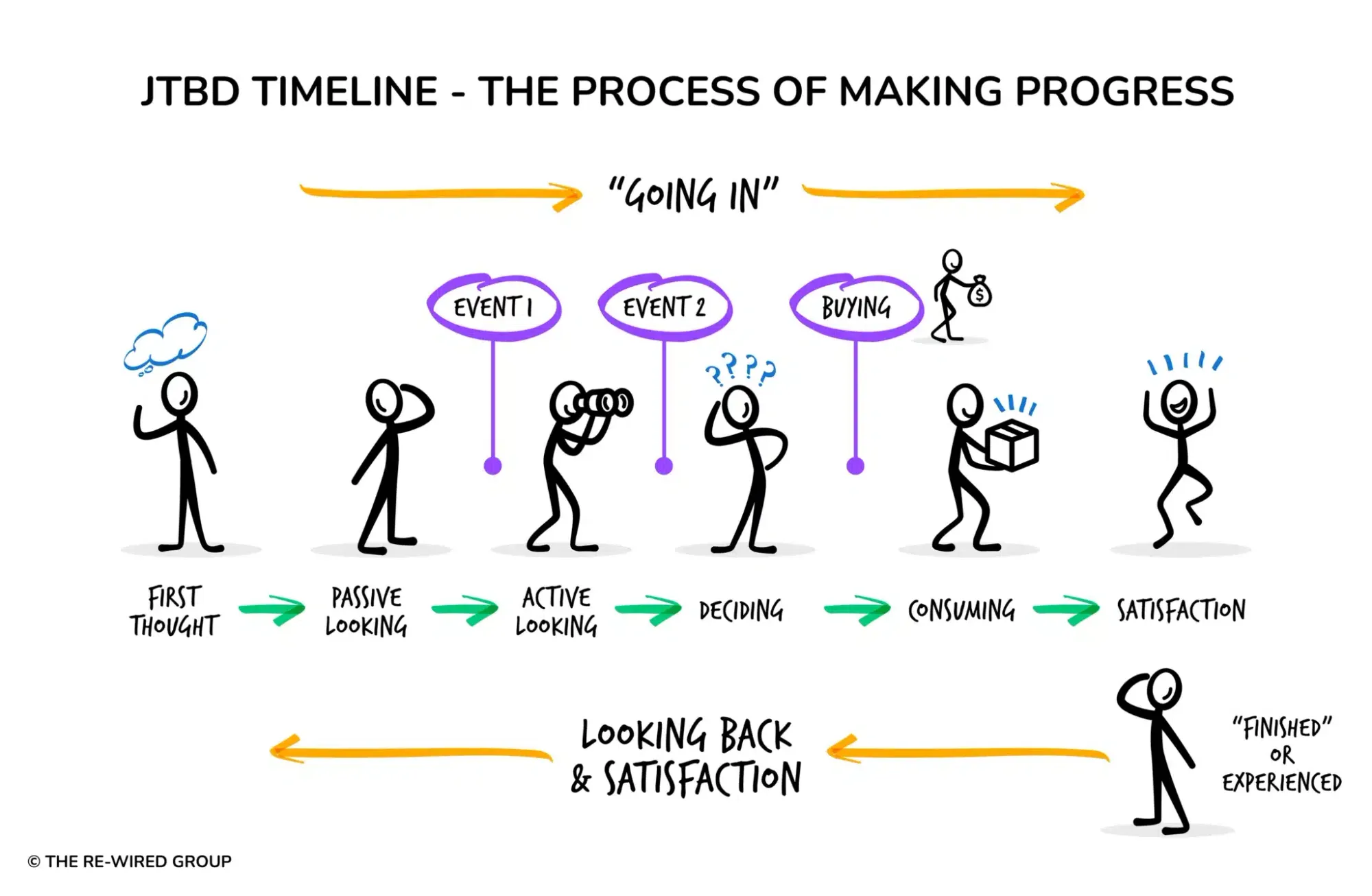

Commoncog runs a membership subscription, and — roughly speaking — has two parallel paths in its growth loop.

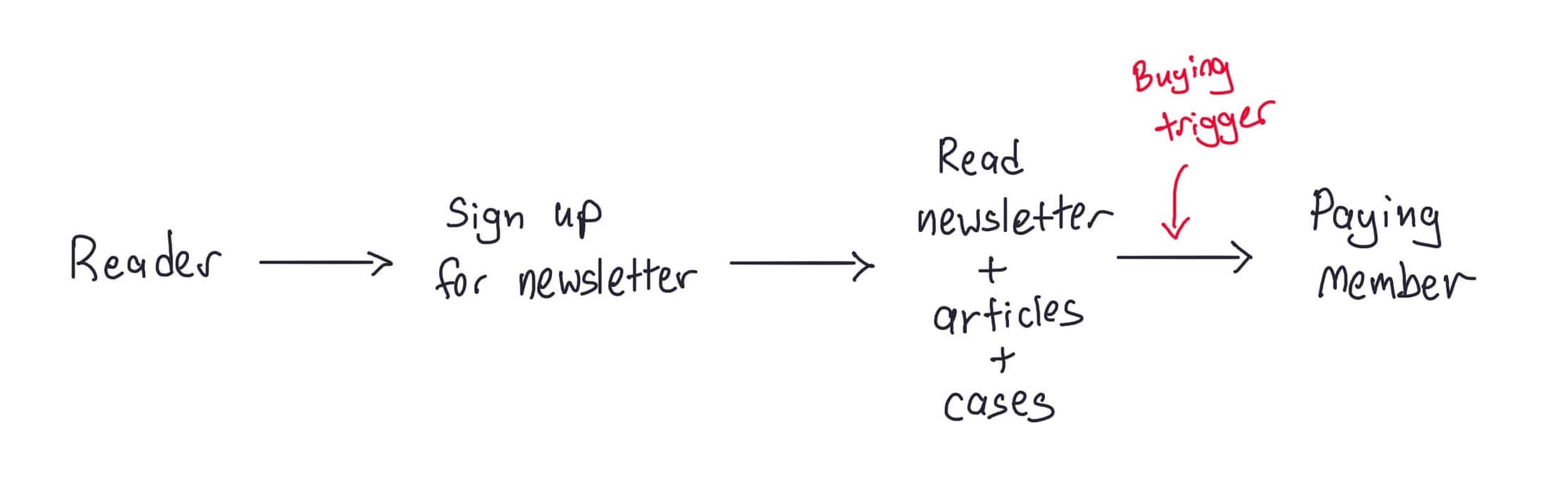

In the first path, a reader signs up for the newsletter, and becomes a regular subscriber for some indeterminate amount of time. At some point, they become a paying member.

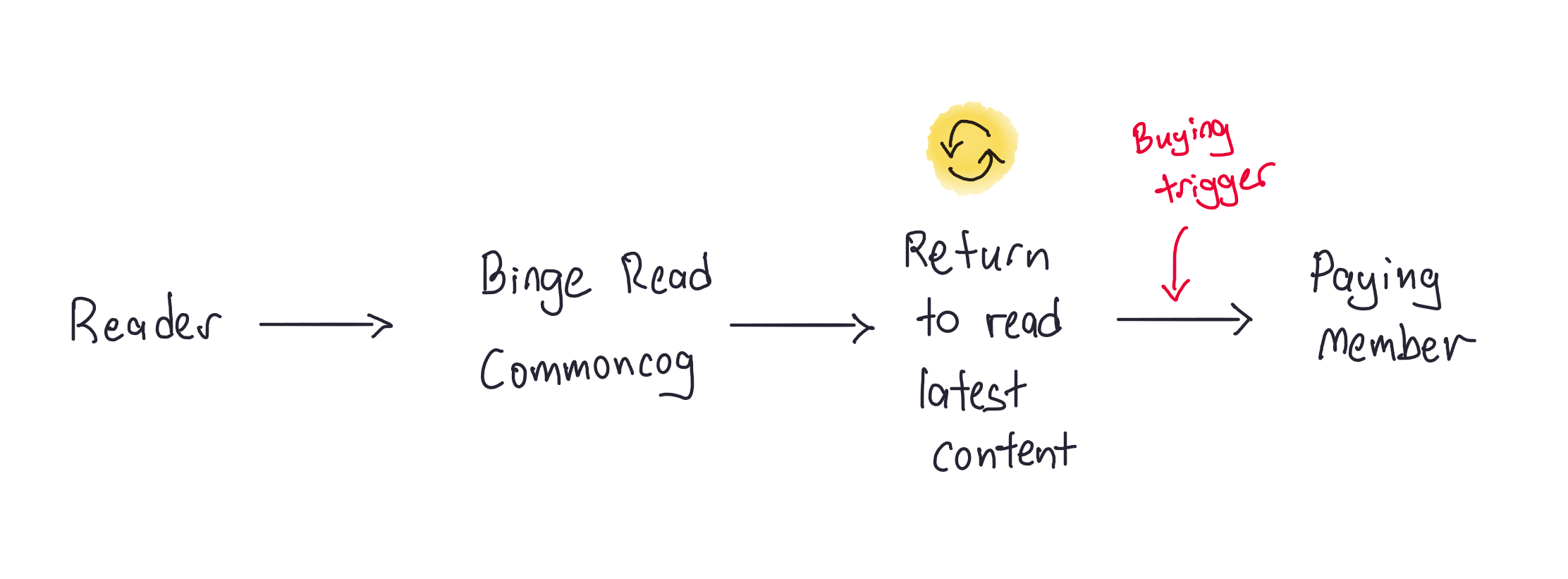

In the second path, a reader discovers Commoncog, and becomes a repeat reader. They return to the site over a period of many days, then weeks, then months. They never once sign up for the newsletter. After some indeterminate amount of time, they become a paying member.

We know both paths exist because of a) common sense, but also b) we’ve had multiple random conversations with members over the years.

What we didn’t know — or had even bothered to find out — was how many paying members became paying members through the first path vs the second. I assumed that more members came from the first path (reader → newsletter subscriber → paying member) than the second (reader → repeat reader → paying member), because I was influenced by the growth of newsletter platform Substack, and assumed that whatever applied to newsletters also applied to Commoncog.

Boy was I mistaken.

During the JTBD interviews, we began to realise that members who became paying customers through the first path experienced a different timeline from readers who became paying customers through the second path.

To cut a long story short, members who had been newsletter subscribers became a member in the following manner:

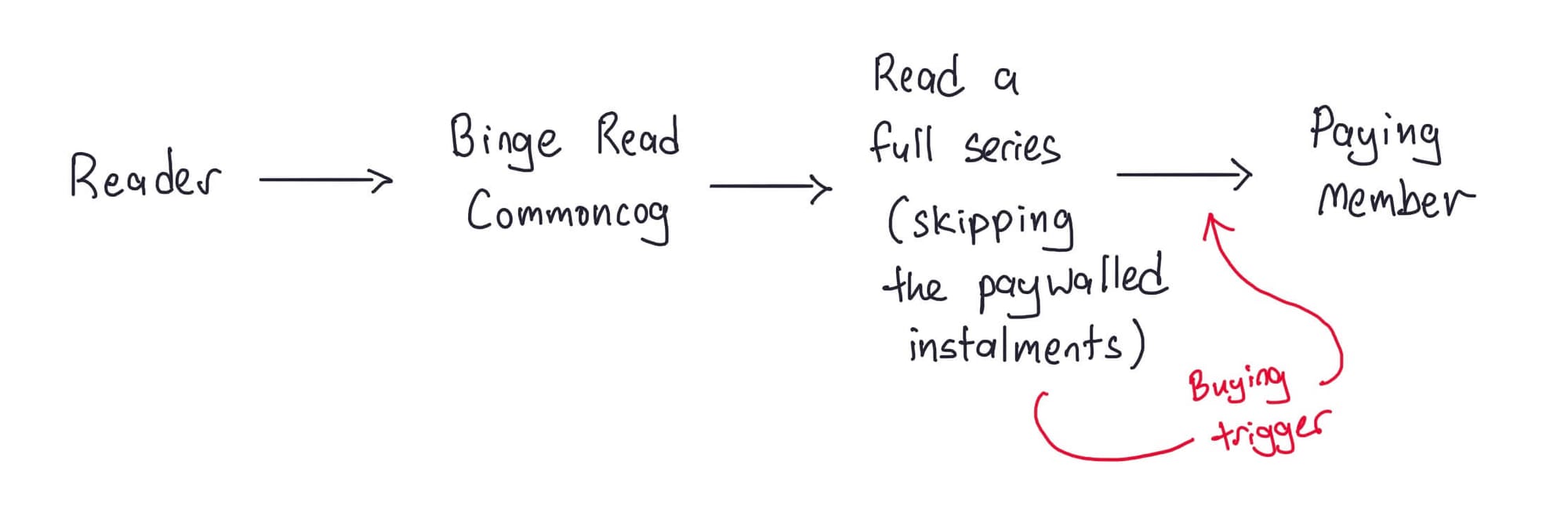

On the other hand, members who become paying customers through the second path went through the following journey:

In fact, this broad pattern of behaviour came up again and again in the set of customers we talked to. Intriguingly, nearly every member who experienced the second path bought because of a paywalled entry in a series.

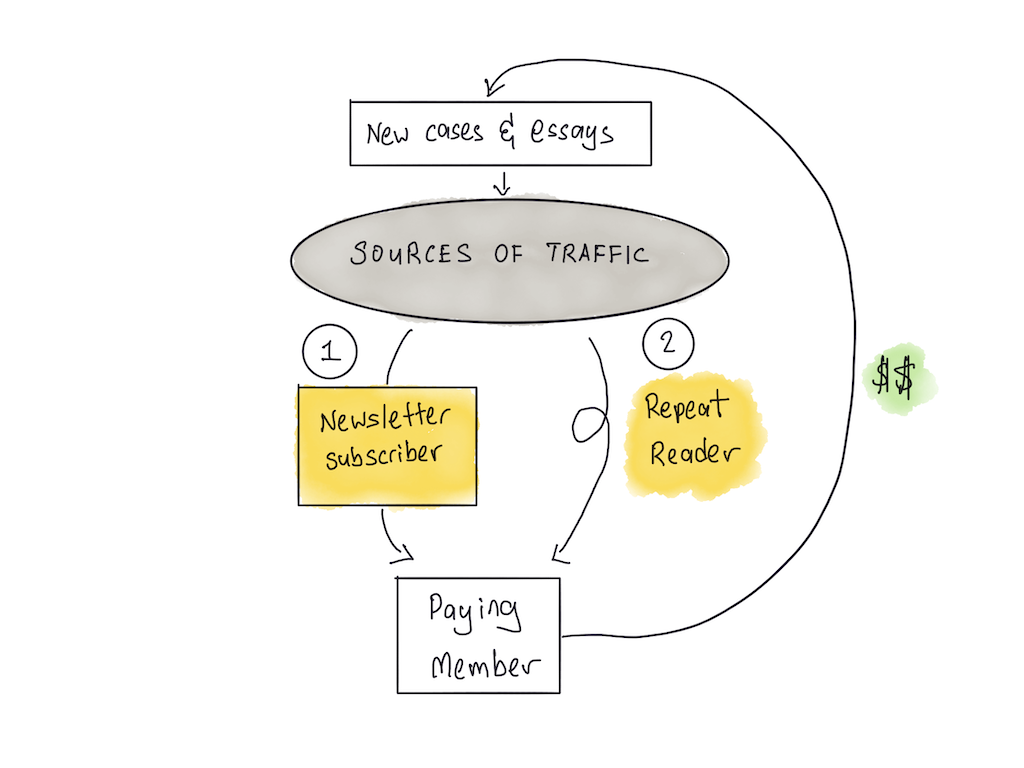

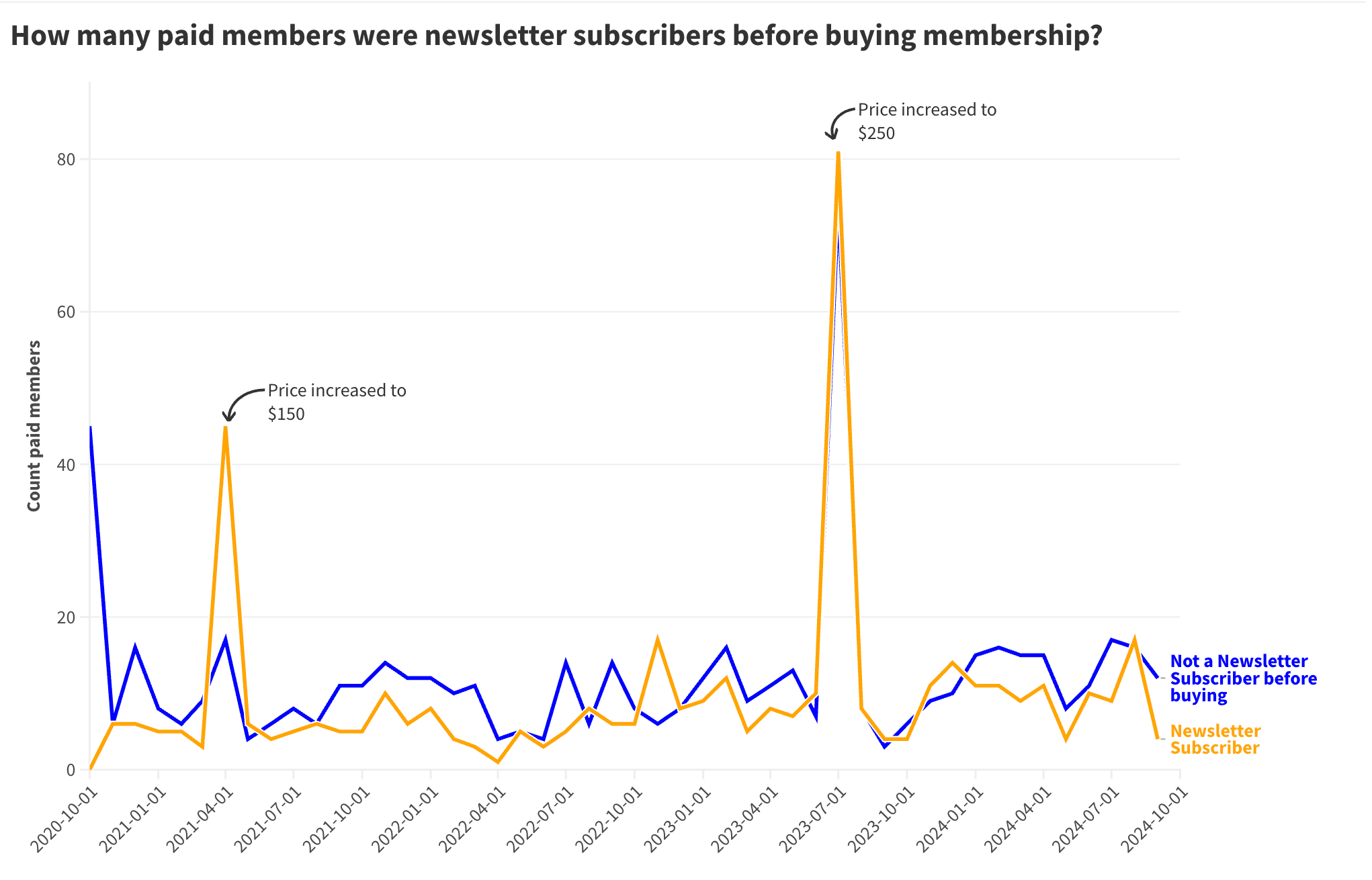

At this point we needed to put some numbers around this. My wife, Hien, is a data analyst, and she helps us put together our WBR. She ran the numbers.

We learnt that 56.5% of members came from the second path. Only 43.5% were newsletter subscribers before purchasing.

That meant that our causal model of Commoncog’s growth was wrong. More people became paying Commoncog members after hitting a paywalled article (in the context of a series) than they did from becoming a free newsletter subscriber.

Huh.

Hien then created the following visualisation:

This was interesting, for a different reason.

In the JTBD framework, purchases are made because of a buying trigger — that is, some … thing that gets the buyer to take action. The most common form of a buying trigger is a time wall, which is basically a deadline. This time wall might be manufactured (“10% off until Friday!”), or it might be natural (“I need a new laptop before my trip to London next week”). It might also be made up (“I will buy this course before the end of the day.”)

What this graph shows us is that in any given month, the number of paying members who bought because of a paywalled article would typically outstrip those who bought after becoming a regular newsletter reader. But in two of those months, newsletter readers who became paying members far outstripped the number of new members who were website readers. Those two months corresponded to the two times we increased prices of the membership program. In both those cases, I signalled the price increase a month before the actual prices went up.

In other words, the price increase served as a time wall. This wall worked on both website readers and newsletter subscribers … but conversion was higher from newsletter subscribers. One conclusion might be that Commoncog’s email list contains a list of potential customers stuck in passive looking. Creating a time wall should nudge these individuals towards a buy decision.

The purpose of data is knowledge. Knowledge is defined as ‘theories or models that allow us to better predict the results of our business actions.’ It is not enough to have findings, in the way that I’ve described, above — we want to know how it can be predictive because we want to be able to act on it.

So how is this knowledge?

One piece of knowledge is clear: more people become paying Commoncog members through the second path, so we should focus on that. Notice that this may be stated in the form of a prediction: “if we focus on the second path, we should see higher conversions to paying members.”

But: how? There is, of course, an obvious hypothesis: because the majority of repeat readers paid after encountering a paywalled article (in the context of a series), we should modify the Commoncog site to increase traffic and ease discovery for published series. This may also be stated as a prediction: “if we increase visitor traffic to the Commoncog series, we should see an increase in member conversions, after a delay of two months.”

(Amongst other things, this explains the creation of the Commoncog syllabus page).

Notice that we still have to test this. All we have right now is a correlation. Sure, this is a strong hunch — so many people seem to have bought in the exact same way! — but we can really only know after we’ve tested against reality. Causality only exists if you’ve made a prediction and then verified that the prediction is true.

There is one other hunch that we can chase down. The price increase and subsequent spike in purchases tell us that a good number of mailing list subscribers are in the ‘passive looking’ phase of the buyer’s journey. They’ve considered becoming a Commoncog member in the past, but have not experienced a buying trigger. Creating a time wall (such as sending an expiring discount to the list) should result in a burst of signups.

Of course, whether we want to do that is a different matter. Commoncog doesn’t discount right now. Are there other ways to create a time wall?

I want you to notice a couple of things. First, this finding started out as a qualitative observation from executing a JTBD interview series. We then firmed up the hypothesis by running the numbers — using ‘data as an added sense’.

Then, we turned our findings to action by asking “how is this knowledge?” Which is shorthand for: “what predictions can we make, based on these findings?”Asking this question naturally leads to: “how can we test these predictions to see if they hold up?” — which leads to experiments.

(Note that we run our own Amazon-style Weekly Business Review, so these findings were presented in the context of a broader metrics review. That particular meeting — the one in which we presented these findings — was probably the most interesting one last year, because it caused us to do a major update to the causal model of the business in our heads.)

We may generalise all of this into the following series of steps:

Long-term readers will notice that this is the Plan-Do-Study-Act loop, which we’ve covered extensively in the Becoming Data Driven Series.

But enough about that. Let’s pull back to talk about demand.

In this essay I’ve shown you a handful of things:

This essay has gone on for long enough.

I think it’s about time that we wrap up the entire series. I’ll see you in the next instalment — which will be our last.