LLMs are overused to summarise and underused to help us read deeper.

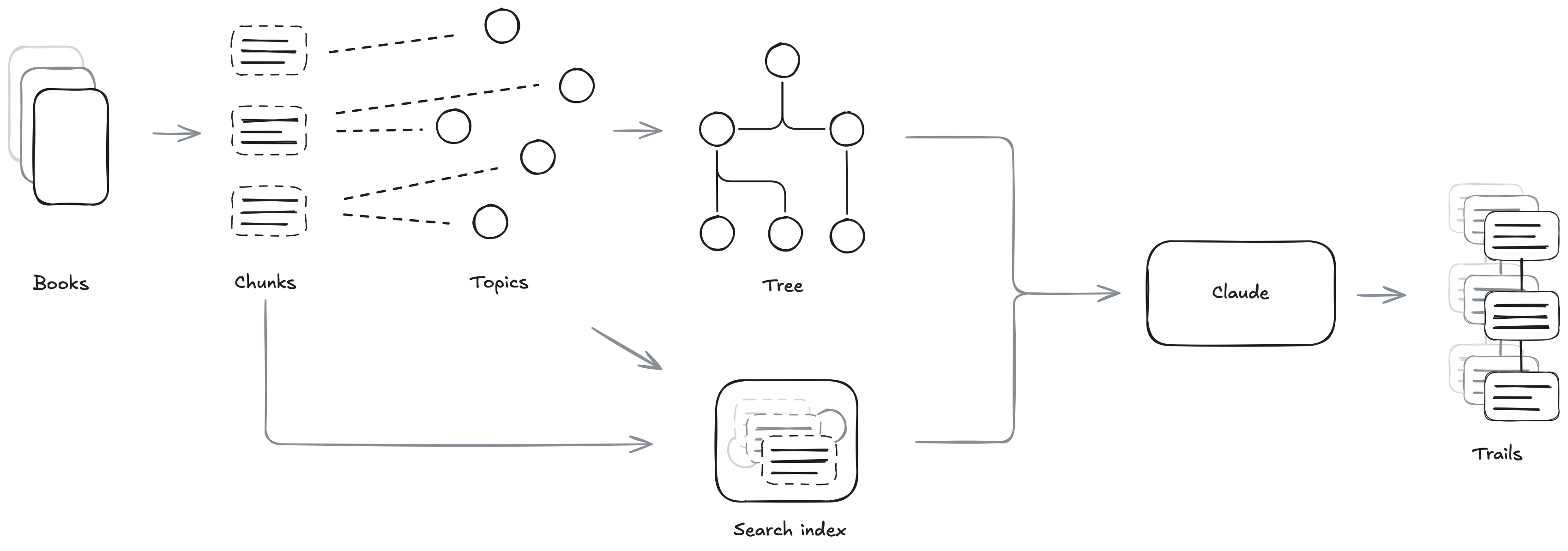

To explore how they can enrich rather than reduce, I set Claude Code up with tools to mine a library of 100 non-fiction books. It found sequences of excerpts connected by an interesting idea, or trails.

Here’s a part of one such trail, linking deception in the startup world to the social psychology of mass movements (I’m especially pleased by the jump from Jobs to Theranos):

How it works

The books were selected from Hacker News’ favourites, which I previously scraped and visualized.

Claude browses the books a chunk at a time. A chunk is a segment of roughly 500 words that aligns with paragraphs when possible. This length is a good balance between saving tokens and providing enough context for ideas to breathe.

Chunks are indexed by topic, and topics are themselves indexed for search. This makes it easy to look up all passages in the corpus that relate to, say, deception.

This works well when you know what to look for, but search alone can’t tell you which topics are present to begin with. There are over 100,000 extracted topics, far too many to be browsed directly. To support exploration, they are grouped into a hierarchical tree structure.

This yields around 1,000 top-level topics. They emerge from combining lower-level topics, and not all of them are equally useful:

- Incidents that frustrated Ev Williams

- Names beginning with “Da”

- Events between 1971 & 1974

However, this Borgesian taxonomy is good enough for Claude to piece together what the books are about.

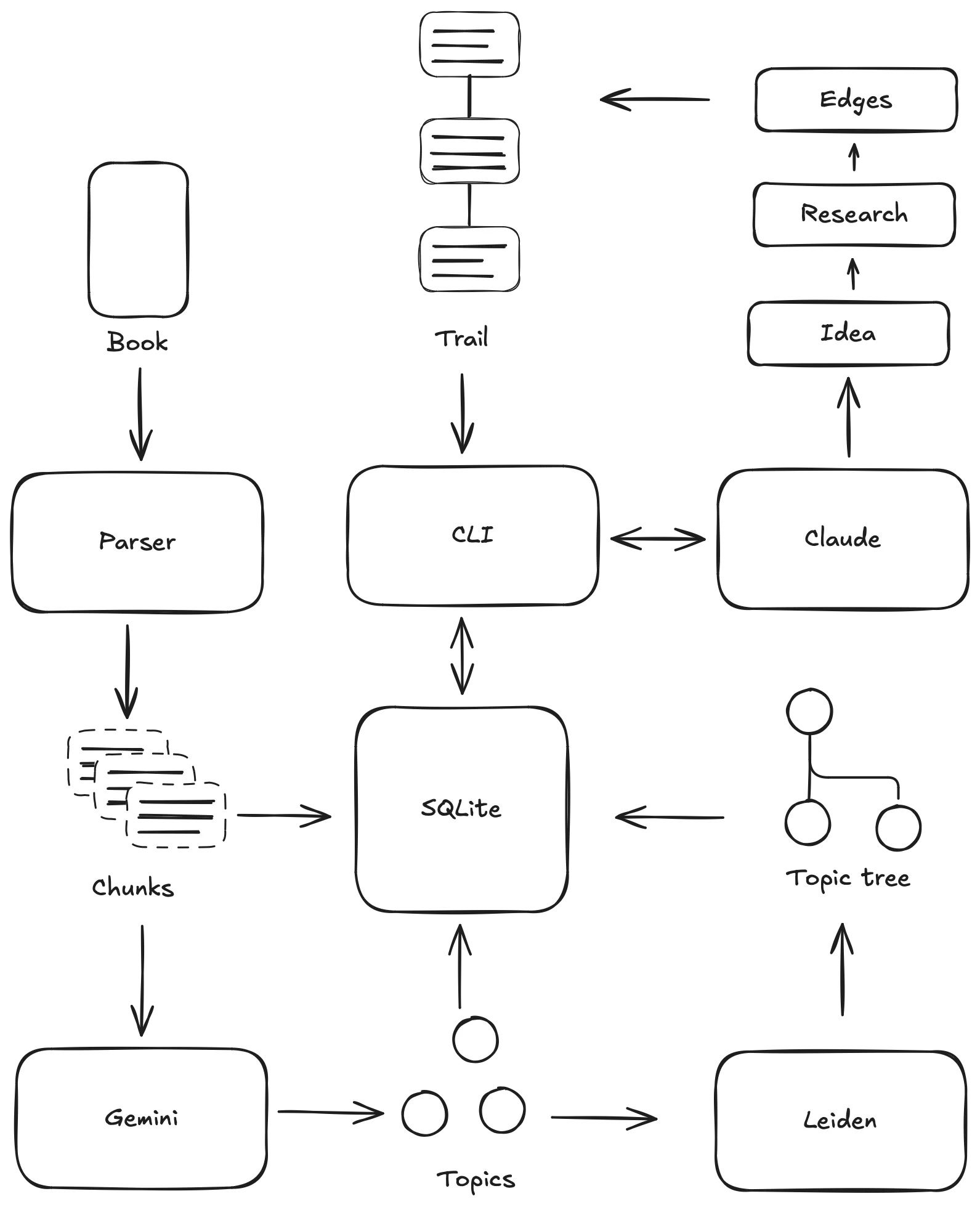

Claude uses the topic tree and the search via a few CLI tools.

- Find all chunks associated with a topic similar to a query.

- Find topics which occur in a window of chunks around a given topic.

- Find topics that co-occur in multiple books.

- Browse topics and chunks that are siblings in the topic tree.

To generate the trails, the agent works in stages.

- First, it scans the library and the existing trails, and proposes novel trail ideas. It mainly browses the topic tree to find unexplored areas and rarely reads full chunks in depth.

- Then, it takes a specific idea and turns it into a trail. It receives seed topics from the previous stage and browses many chunks. It extracts excerpts, specific sequences of sentences, and decides on how best to order them to support an insight.

- Finally, it adds highlights and edges between consecutive excerpts.

What I learned

Claude Code is great for non-coding tasks

Even though I’ve been using Claude Code to develop for months, my first instinct for this project was to consider it as a traditional pipeline of several discrete stages. My initial attempt at this system consisted of multiple LLM modules with carefully hand-assembled contexts.

On a whim, I ran Claude with access to the debugging tools I’d been using and a minimal prompt: “find something interesting.” It immediately did a better job at pulling in what it needed than the pipeline I was trying to tune by hand, while requiring much less orchestration. It was a clear improvement to push as much of the work into the agent’s loop as possible.

I ended up using Claude as my main interface to the project.

The latter opened up options that I wouldn’t have considered before. For example, I changed my mind on how short I wanted excerpts to be. I communicated my new preference to Claude, which then looked through all the existing trails and edited them as necessary, balancing the way the overall meaning of the trail changed. Previously, I would’ve likely considered all previous trails to be outdated and generated new ones, because the required edits would’ve been too nuanced to specify.

In general, agents have widened my ambitions.

Ask the agent what it needs

My focus went from optimising prompts to implementing better tools for Claude to use, moving up a rung on the abstraction ladder.

My mental model of the AI component changed: from a function mapping input to output, to a coworker I was assisting. I spent my time thinking about the affordances that would make the workflow better, as if I were designing them for myself. That they were to be used by an agent was a mere detail.

This worked because the agent is now intelligent enough that the way it uses these tools overlaps with my own mental model. It is generally easy to empathise with it and predict what it will do.

Initially I watched Claude’s logs closely and tried to guess where it was lacking a certain ability. Then I realised I could simply ask it to provide feedback at the end and list the functionality it wished it had. Claude was excellent at proposing new commands and capabilities that would make the work more efficient.

Claude suggested improvements, which Claude implemented, so Claude could do the work better. At least I’m still needed to pay for the tokens — for now.

Novelty is a useful guide

It’s hard to quantify interestingness as an objective to optimise for.

As a sign of the times, this novelty search was implemented in two ways:

- By biasing the search algorithm towards under-explored topics and books.

- By asking Claude nicely.

A topic’s novelty score was calculated as the mean distance from its embedding’s k nearest neighbors. A book’s novelty score is the average novelty of the unique topics that it contains. This value was used to rank search results, so that those which were both relevant and novel were more likely to be seen.

On a prompting level, Claude starts the ideation phase by looking at all the existing trails and is asked to avoid any conceptual overlap. This works fairly well, though it is often distracted by any topics related to secrecy, systems theory, or tacit knowledge.

It’s as if the very act of finding connections in a corpus summons the spirit of Umberto Eco and amps up the conspiratorial thinking.

How it’s implemented

- EPUBs are parsed using

selectolax, which I picked over BeautifulSoup for its speed and simpler API. - Everything from the plain text to the topic tree is stored in SQLite. Embeddings are stored using

sqlite-vec. - The text is split into sentences using

wtpsplit(thesat-6l-smmodel). Those sentences are then grouped into chunks, trying to get up to 500 words without breaking up paragraphs. - I used

DSPyto call LLMs. It worked well for the structured data extraction and it was easy to switch out different models to experiment. I tried its prompt optimizers before I went full agentic, and their results were very promising. - I settled on Gemini 2.5 Flash Lite for topic extraction. The model gets passed a chunk and is asked to return 3-5 topics. It is also asked whether the chunk is useful, in order to filter out index entries, acknowledgements, orphan headers, etc. I was surprised at how stable these extracted topics were: similar chunks often shared some of the exact same topic labels. Processing 100 books used about 60M input tokens and ~£10 in total.

- After a couple books got indexed, I shared the results with Claude Opus along with the original prompt and asked it to improve it. This is a half-baked single iteration of the type of prompt optimisation DSPy implements, and it worked rather well.

- Topic pairs with a distance below a threshold get merged together. This takes care of near-duplicates such as “Startup founder”, “Startup founders”, and “Founder of startups”.

- The CLI output uses a semi-XML format. In order to stimulate navigating, most output is nested with related content. For example, when searching for a topic, chunks are shown with the other topics they contain. This allows us to get a sense of what the chunk is about, as well as which other topics might be interesting. There’s probably more token-efficient formats, but I never hit the limit of the context window.

<topics query="deception" count="1">

<topic id="47193" books="7" score="0.0173" label="Deception">

<chunk id="186" book="1">

<topic id="47192" label="Business deal"/>

<topic id="47108" label="Internal conflict"/>

<topic id="46623" label="Startup founders"/>

</chunk>

<chunk id="1484" book="4">

<topic id="51835" label="Gawker Media"/>

<topic id="53006" label="Legal Action"/>

<topic id="52934" label="Maskirovka"/>

<topic id="52181" label="Strategy"/>

</chunk>

<chunk id="2913" book="9">

<topic id="59348" label="Blood testing system"/>

<topic id="59329" label="Elizabeth Holmes"/>

<topic id="59352" label="Investor demo"/>

<topic id="59349" label="Theranos"/>

</chunk>

</topic>

</topics>-

Topics are embedded using

google/embeddinggemma-300mand reranked usingBAAI/bge-reranker-v2-m3. -

Many CLI tools require loading the embedding model and other expensive state. The first call transparently starts a separate server process which loads all these resources once and holds onto them for a while. Subsequent CLI calls use this server through Python’s

multiprocessing.connection. -

The topic collection is turned into a graph (backed by

igraph) by adding edges based on the similarity of their embeddings and the point-wise mutual information of their co-occurrences. -

The graph is turned into a tree by applying Leiden partitioning recursively until a minimum size is reached. I tried the Surprise quality function because it had no parameters to tweak, and found it to be good enough. Each group is labelled by Gemini based on all the topics that it contains.

-

Excerpts are cleaned by Gemini to remove EPUB artifacts, parsing errors, headers, footnotes, etc. Doing this only for excerpts that are actually shown, instead of during pre-processing, saved a lot of tokens.