In the 1990s, Apple struggled to bring the original Mac OS—originally written in 1984 for the resource-constrained Macintosh 128K machine—up to modern operating system standards. The story of how OS X came to be is thrilling in its own right, but suffice it to say that Apple ended up buying Steve Jobs' second computer company, NeXT, and using its NeXTSTEP operating system as the basis of a new generation of Macs.

Apple announced the acquisition of NeXT on December 20, 1996, noting it wanted NeXT's object-oriented software development technology and its operating system know-how. As part of the deal, Jobs came back to Apple, eventually taking over as CEO and making the company into the consumer electronics giant it is today. Sixteen years later, several technologies developed or championed by NeXT still survive in OS X and in its mobile cousin, iOS. This week, we remember some of those technologies which continue to power key features of Apple's devices.

UNIX

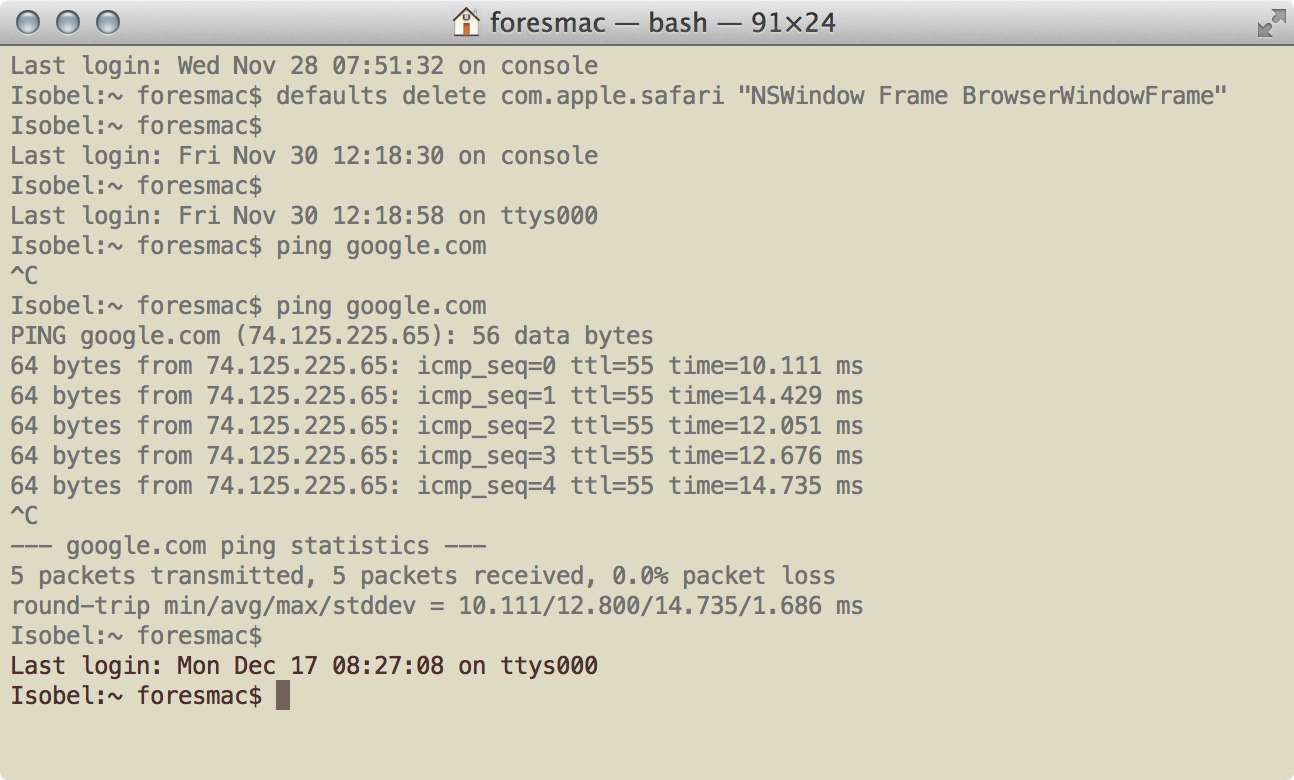

We consulted several developers with knowledge of both NeXTSTEP and OS X; they universally agreed that one crucial feature of NeXTSTEP that made OS X and iOS what they are today is its underlying UNIX roots. Beneath all the slickly styled windows, icons, scrolling lists, and buttons sits a rock-solid, certified UNIX operating system.

UNIX was originally conceived in 1969 by Bell Labs' Ken Thompson for the PDP-7 minicomputer. Its development throughout the early '70s led to the development of the C programming language by Thompson's colleague Dennis Ritchie. UNIX at its core was meant to be a powerful operating system for the massive computers of the day, but it could also be easily programmed and controlled by developers using a simple video terminal.

Underneath OS X's pretty graphical interface is a version of the UNIX operating system.

That same basic system powers both the Mac sitting on your desk and the iPhone resting in your pocket. By basing OS X—and later, iOS—on UNIX, Macs were finally able to enjoy important operating system features like protected memory, pre-emptive multitasking, and daemon-based services.

Graybeards may remember the days of the classic Mac OS. Some errant Photoshop plug-in could crash your entire Mac, or the Mac OS might come screeching to a halt while you dug through menus looking for some arcane command. Protected memory means that most app crashes on OS X would no longer take your whole machine down with them. Pre-emptive multitasking means that your computer could keep chugging along doing other tasks even while one application might be tied up using some of the system's resources.

With pre-emptive multitasking, UNIX-based operating systems can also use daemons, small programs that continually run in the background. Daemons sit back and wait for a signal to spring into action; they handle most of the background tasks like connecting to networked printers on your Mac or playing music while you play Words With Friends on your iPhone.

In addition, because OS X is fully POSIX-compliant—a defined set of standards that all UNIX operating systems adhere to—porting freely available tools or open source software to OS X is (relatively) straightforward. For instance, the popular FFmpeg audio/video encoder, originally developed for Linux, also powers some video encoding apps for OS X, such as Handbrake.

Objective-C

The Objective-C programming language was used to develop software for the NeXTSTEP operating system, and it carried on to OS X and iOS. It's an object-oriented programming language developed as a superset of the original C language so that both object-oriented Objective-C code and procedural C code can be combined in the same program.

Steve Jobs was a huge proponent of object-oriented programming and he largely built NeXT around giving developers tools to program in this style. At a high-level, object-oriented programming uses a set of "objects" which are defined in code to have certain characteristics and capabilities. A developer can then mix and match these objects, passing messages from one to the other in order to accomplish a particular task. Developers don't need to know the underlying code of the objects, only what messages the object responds to and what responses it can generate.

(Imagine an "adding" object that you could send a message containing two numbers; its response might naturally be the sum of those two numbers.)

While Objective-C has its detractors—mainly for its verbose, Smalltalk-style syntax—Apple has worked to improve the language by adding features like dot syntax, blocks, and automatic reference counting. The company also significantly improved compiled code by replacing the traditional C compiler gcc with Clang and LLVM. (A simple Objective-C program is below.)

// "Hello World" program example

// adapted from http://cupsofcocoa.com/

// by Rob @tolar Haining

#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[]){

@autoreleasepool {

NSDate *now = [NSDate date];

NSLog (@"Hello, World! The current date is: %@", now);

}

return 0;

}

Jobs said in a 1995 interview (while still at NeXT) that object-oriented development would revolutionize how we created software, compared to the previous 20 or 30 years. The developers we spoke to tended to agree that his prediction came true.

"Objective-C directly inspired Java and C# and has changed how almost everyone programs, even if they’re not writing for Apple’s machines," said developer Wil Shipley, who got his start writing software for NeXT computers. "We saw the invention of the fricking World Wide Web on NeXTSTEP. It's not a coincidence; it was a machine that was a dream to program for."

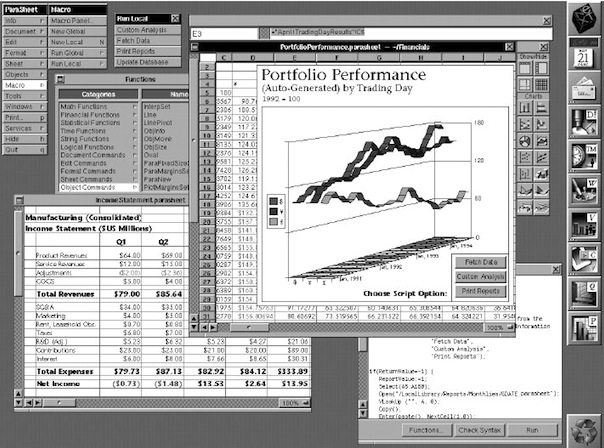

Shipley also noted that several apps we still use today on OS X were inspired by or adapted from software originally developed for the NeXT platform, including Numbers (née Parasheet), Keynote (née Concurrence), Pages, and OmniGraffle (née Diagram!).

You can see the roots of Apple's Numbers, the spreadsheet app from its iWork suite, in ParaSheet for NeXTSTEP. Credit: kevra.org

AppKit framework

In addition to using the Objective-C language, NeXT also developed collections of pre-built objects which developers could use to build software. Many of these were collected in the AppKit framework, which Apple adapted into Cocoa for OS X and later into Cocoa Touch for iOS. These frameworks help eliminate some of the tedious, repetitive coding typically required in application development, letting developers focus on core functionality and usability.

Cocoa and Cocoa Touch frameworks include all the basic building blocks and functionality necessary for most modern software, but Cocoa's NeXTSTEP roots are still apparent in object class names like NSArray, which are still prepended with the "NS" prefix.

"I have always believed that if you give programmers a boost, you’re going to see amazing stuff," Shipley explained. "What would the iPhone (and iOS) be today without the SDK that came [in 2008]? I’d argue it'd just be a iPod—still a great seller, but not something that has changed every part of our lives."

Developer Mike Lee, who cut his teeth with Shipley at Delicious Monster and at Apple in Developer Relations before striking off on his own at New Lemurs, explained the connection between OS X's and iOS's UNIX underpinnings, Objective-C programming language, and Cocoa frameworks this way:

There is a relationship between most of the things listed here. The computer is UNIX, and C is the language of UNIX. Objective-C is a human-oriented language [variant], Smalltalk implemented in C. The AppKit and its Cocoa kin let us talk to the user with the same ease with which we talk to the machine. We [developers] are the diplomats between people and computers.

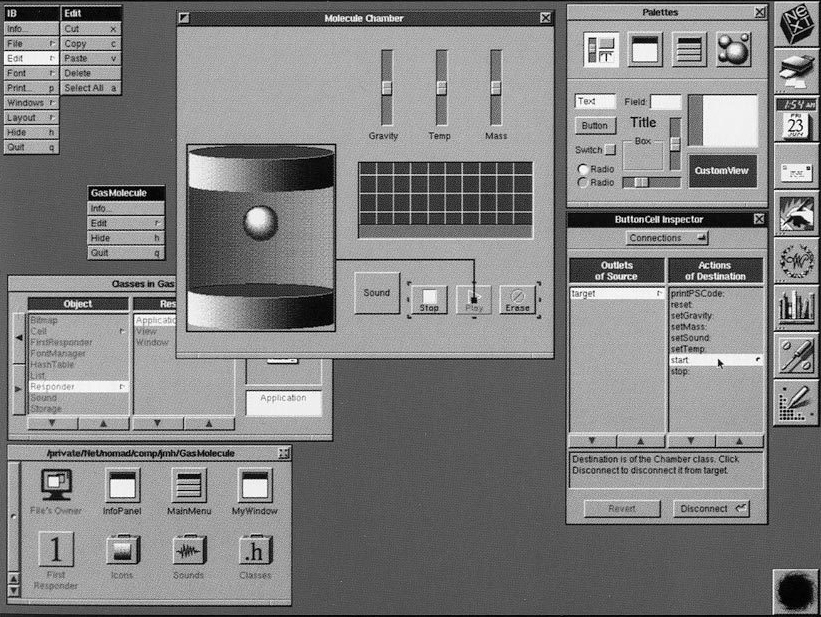

Interface Builder

An important NeXTSTEP developer tool that still exists today is Interface Builder. This app allowed developers to merely drag and drop user interface elements into a view, creating an app's user interface. Need a button to access a certain feature? Drag one in. Need a drop-down list to let the user choose from several possible options? Click and it's there.

Interface Builder was packaged along with Project Builder. The two apps together provided even a novice developer everything needed to build a GUI application from scratch.

Interface Builder for NeXTSTEP.

Better yet, developer Gus Mueller told Ars, was the price. "It was like a pricy IDE which they made free for folks," he said.

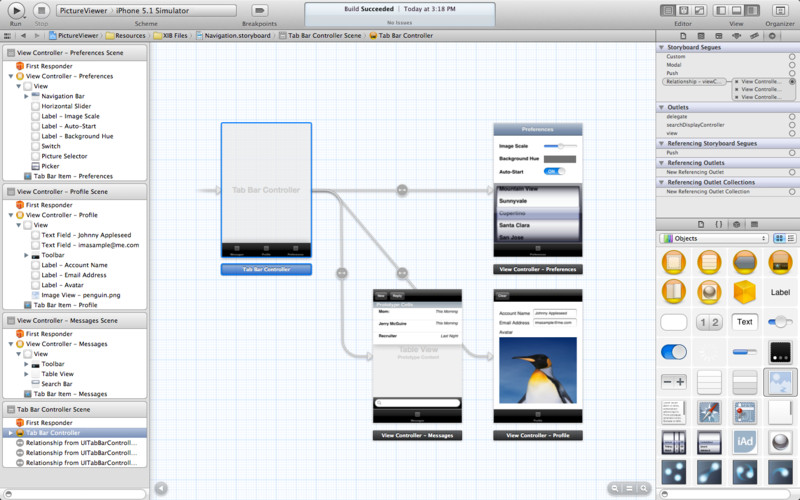

Interface Builder was a separate app for many years, both as part of NeXTSTEP and OS X. Apple has since integrated its functionality directly into its improved version of Project Builder, now called Xcode. Along with analysis and debugging tools, Apple still gives away everything needed to build apps for the Mac, iPhone, or iPad.

Interface Builder is now directly integrated into Xcode.

Display PostScript

Not all NeXT technologies that live on in OS X or iOS are developer-focused. One obvious technology that users can see—though it exists in a quite different form today—is Display PostScript.

Computers with a graphical user interface in the '90s, including Mac OS, used a grid of pixels to draw everything on the screen. Every window, button, text block, etc., would all be drawn one pixel at a time in a one-to-one mapping.

NeXTSTEP instead used Display PostScript, a variation of Adobe's page-description language for laser printers, to draw onscreen windows and text. This meant that text and vector-based elements would always be drawn at the sharpest resolution possible, independent of whatever graphics card or monitor was attached. Actually drawing fonts and other elements was abstracted away from the graphics hardware until the final rendering on-screen.

OS X and iOS use a different technology, called Quartz, but it's based on similar concepts. Quartz has the PDF page description language at its core instead of PostScript. In addition to generating sharp windows and text, the system also gives OS X users the native ability to view and create PDF files.

Bundles

OS X and iOS both use a concept from NeXTSTEP called "bundles." Bundles are little more than special folders containing multiple files needed for a particular application or file type. The operating system at a low level sees these bundles as a folder with files (or more folders!) inside, but at a high-level the user sees bundles as single files represented by an icon.

Two common bundles that users often interact with on the desktop are apps and iWork files. An app bundle contains the executable code file along with custom graphic resources, icons, configuration files, and more. A Keynote presentation, in similar fashion, will contain a binary layout file, along with embedded graphics, custom fonts, and template elements needed to open and recreate the presentation in Keynote. (You can control-click on bundles in the Finder to dig around their contents.)

Column file browsing

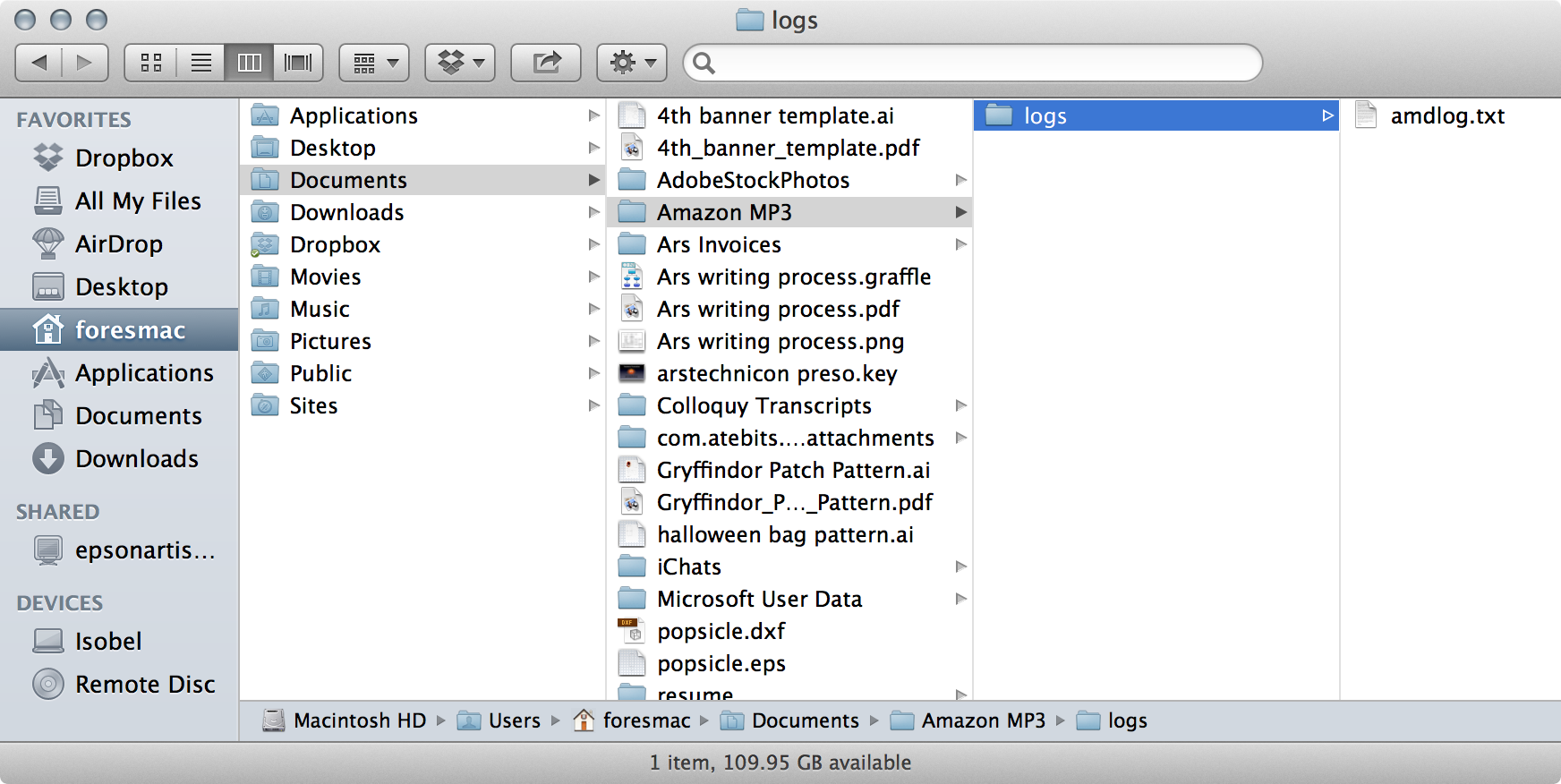

An important interface element that carried over from NeXTSTEP to OS X is the column file browser. Before OS X, classic Mac OS Finder windows could show either a grid of icons or a sorted list of the files contained in a particular folder. While Apple kept these views in the Finder, it also added a hierarchal browsing view that uses a series of columns to drill down into folders.

The Finder in OS X still includes NeXTSTEP's hierarchal column file browser.

On the left side of a column view, you typically select a root source like "Macintosh HD" or your own "Documents" folder. Clicking a folder opens a column to the right with the contents of that folder. Click another folder and its contents open in a new column to the right. You can keep clicking folders to navigate the sometimes byzantine organization of any particular folder or disk drive.

Services

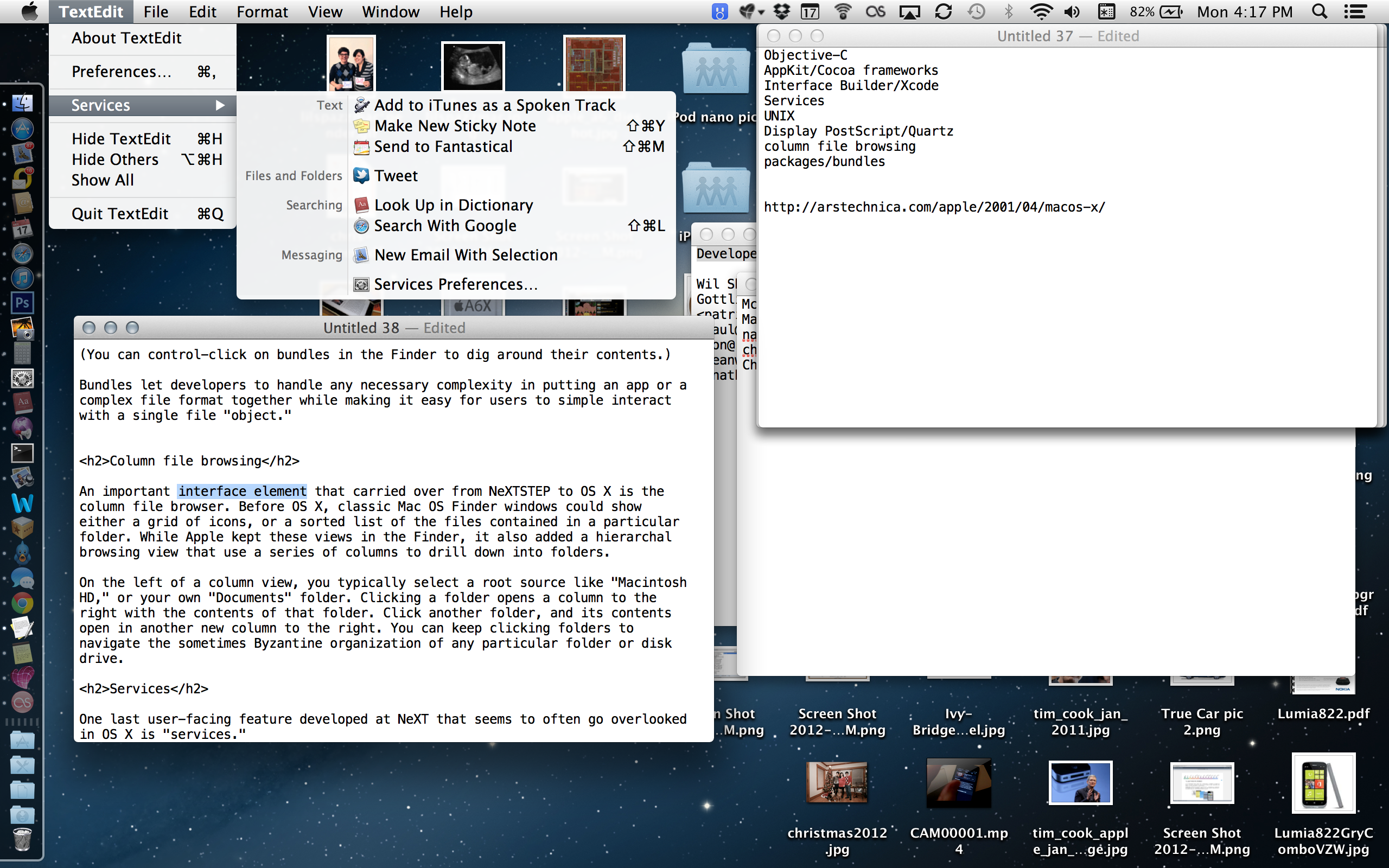

One last user-facing feature developed at NeXT that often goes overlooked in OS X is "services." Applications and system components can tell OS X that they can perform certain actions on certain data elements, such as text, images, or other bits of data. With some of this data selected, you can click on App > Services and see what options are available for that data.

For instance, with some text selected in TextEdit, possible services are: looking up the text in Dictionary, tweeting the text with Twitter, creating a new e-mail with the selected text in the body, or using OS X's text-to-speech capabilities to convert the text into a spoken word track in iTunes.

Services can give you powerful, even unexpected new ways to use your data.

Some services are available via contextual menus, so you may have seen some of these options before by control-clicking on some text or other data. Some services even have keyboard or gesture shortcuts, like Cmd-shift-3 to take a screen shot, for instance, or tapping on a word with three fingers to do a Dictionary look-up.

These services aren't always widely advertised, and not all of them show up in contextual menus. But the Services menu is always there, offering extra functionality or time-saving shortcuts for those willing to find them.

Looking back, moving forward

Many of the technologies described here were developed throughout the late '80s and early '90s (UNIX goes back as far as 1969!). Yet even 16 years after Apple's acquisition of NeXT, these technologies and more give us a lot to work with that we still use in OS X today. Is there something else we didn't mention that is near and dear to your (Mac-using) heart? Let us know what those features are and why they mean so much to your daily life.

Listing image: Aurich Lawson