The craft of AI-assisted software creation is substantially about correctly managing units of work.

When I was new to this emerging craft of AI-assisted coding, I was getting lousy results, despite the models being rather intelligent. Turns out the major bottleneck is not intelligence, but rather providing the correct context.

Andrej Karpathy, while referencing my earlier article on this topic, described the work of AI-assisted engineering as “putting AI on a tight leash”. What does a tight leash look like for a process where AI agents are operating on your code more independently than ever? He dropped a hint: work on small chunks of a single concrete thing.

The right sized unit of work respects the context

I like the term context engineering, because it has opened up the vocabulary to better describe why managing units of work is perhaps the most important technique to get better results out of AI tools. It centers our discussion around the “canvas” against which our AI is generating code.

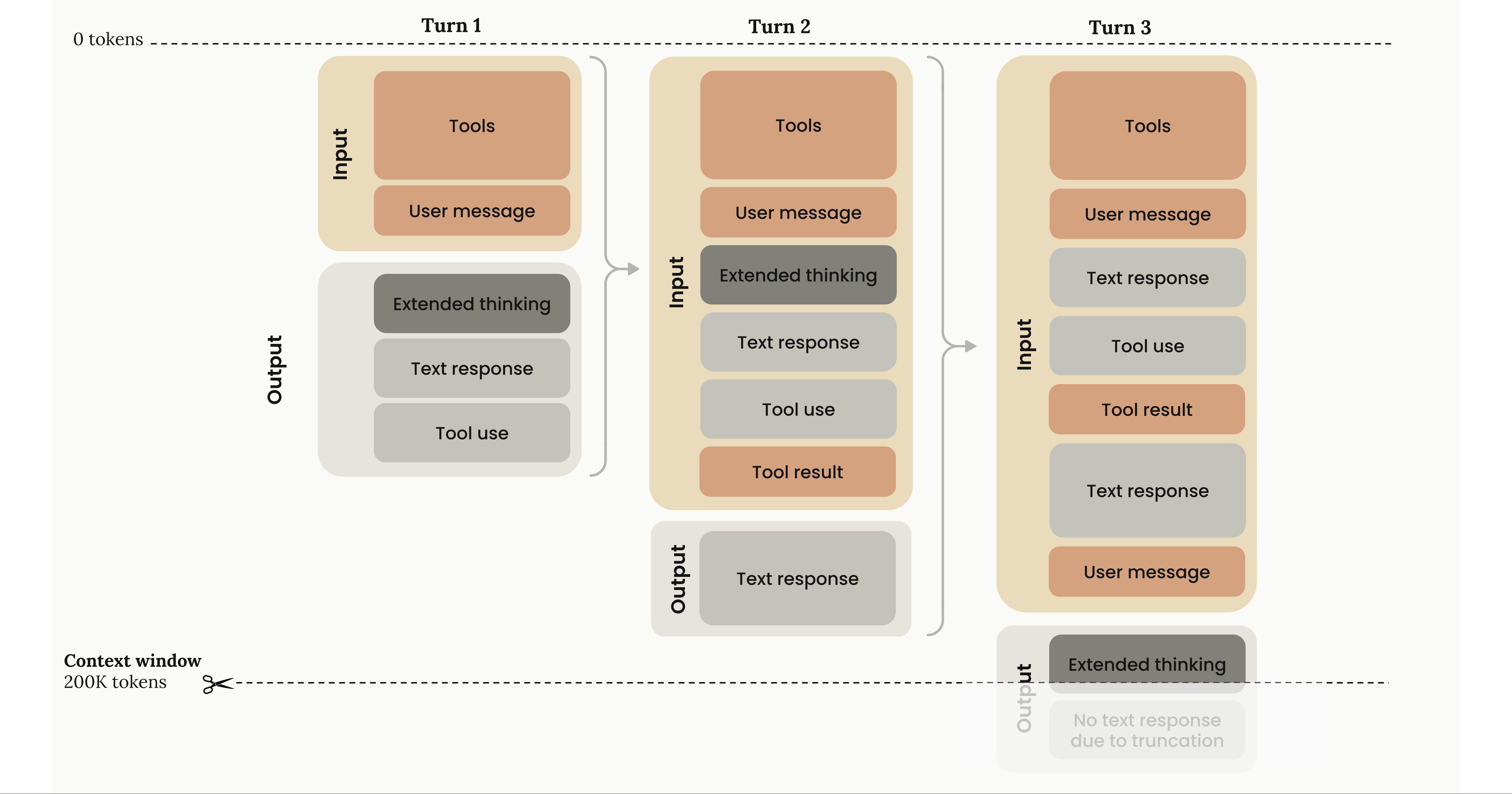

I like Anthropic’s visualisation from their docs:

The generated output of the LLM is a sample of the next token probability. Every time we generate a token, what has already been generated in the previous iteration is appended to the context window. What this context window looks like has a huge influence on the quality of your generated output.

Drew Breunig wrote an excellent article about all kinds of things that can go wrong with your context and proposed various techniques to fix them.

The best AI-assisted craftsmen are often thinking about the design and arrangement of their context to get the AI to one-shot a solution. This is tricky and effortful, contrary to what the AI coding hype suggests.

If you don’t provide the necessary information in the context to do a good job, your AI will hallucinate or generate code that is not congruent with the practices of your codebase. It is especially brittle at integration points of your software system.

On the other hand, if you fill up the context with too much information, and the quality of your output degrades, because of a lack of focused attention.

Breaking down your task into “right-sized” units of work, which describe just the right amount of detail is perhaps the most powerful lever to improve your context window, and thus the correctness and quality of the generated code.

The right sized unit of work controls the propagation of errors

Time for some napkin maths.

Let’s say your AI agent has a 5% chance of making a mistake. I’m not just referring to hallucinations—it could be a subtle mistake because it forgot to look up some documentation or you missed a detail in your specification.

In an agentic multi-turn workflow, which is what all coding workflows are converging to, this error compounds. If your task takes 10 turns to implement, you will have a (1 – 0.95)10 = 59.9% chance of success. Not very high.

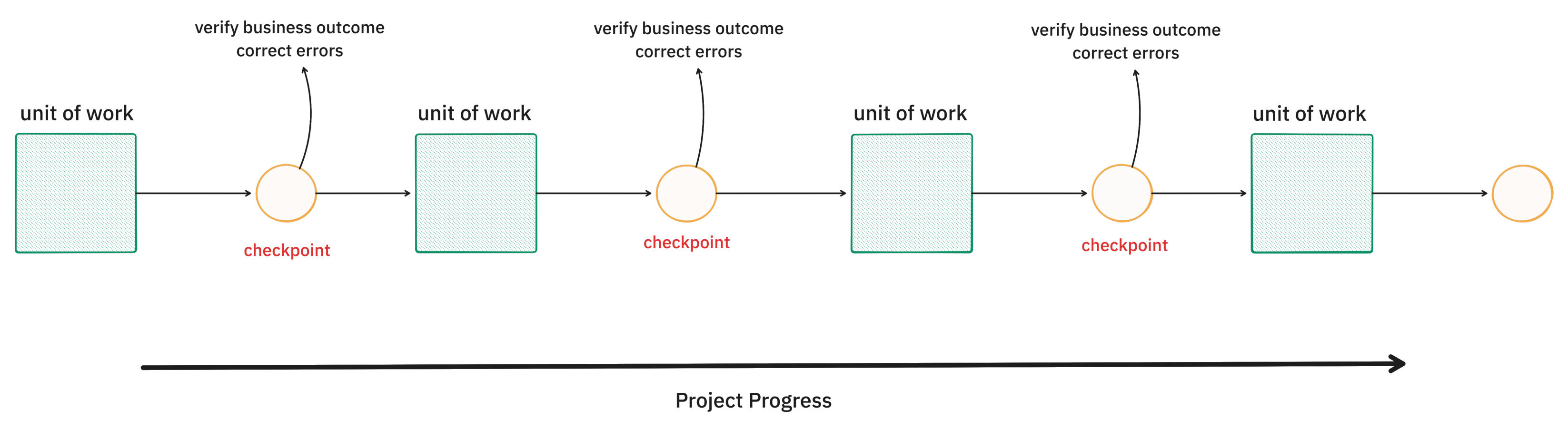

Utkarsh Kanwat in his blog post has made the same argument. His conclusion was that any AI agent would need some kind of pause-and-verify gating mechanism at each step for a long-horizon task.

| Per-action | Overall Success Rate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 turns | 10 turns | 20 turns | 50 turns | |

| 0.1% | 99.5% | 99.0% | 98.0% | 95.1% |

| 1% | 95.1% | 90.4% | 81.8% | 60.5% |

| 5% | 77.4% | 59.9% | 35.8% | 7.7% |

| 10% | 59.0% | 34.9% | 12.2% | 0.5% |

| 20% | 32.8% | 10.7% | 1.2% | 0.0% |

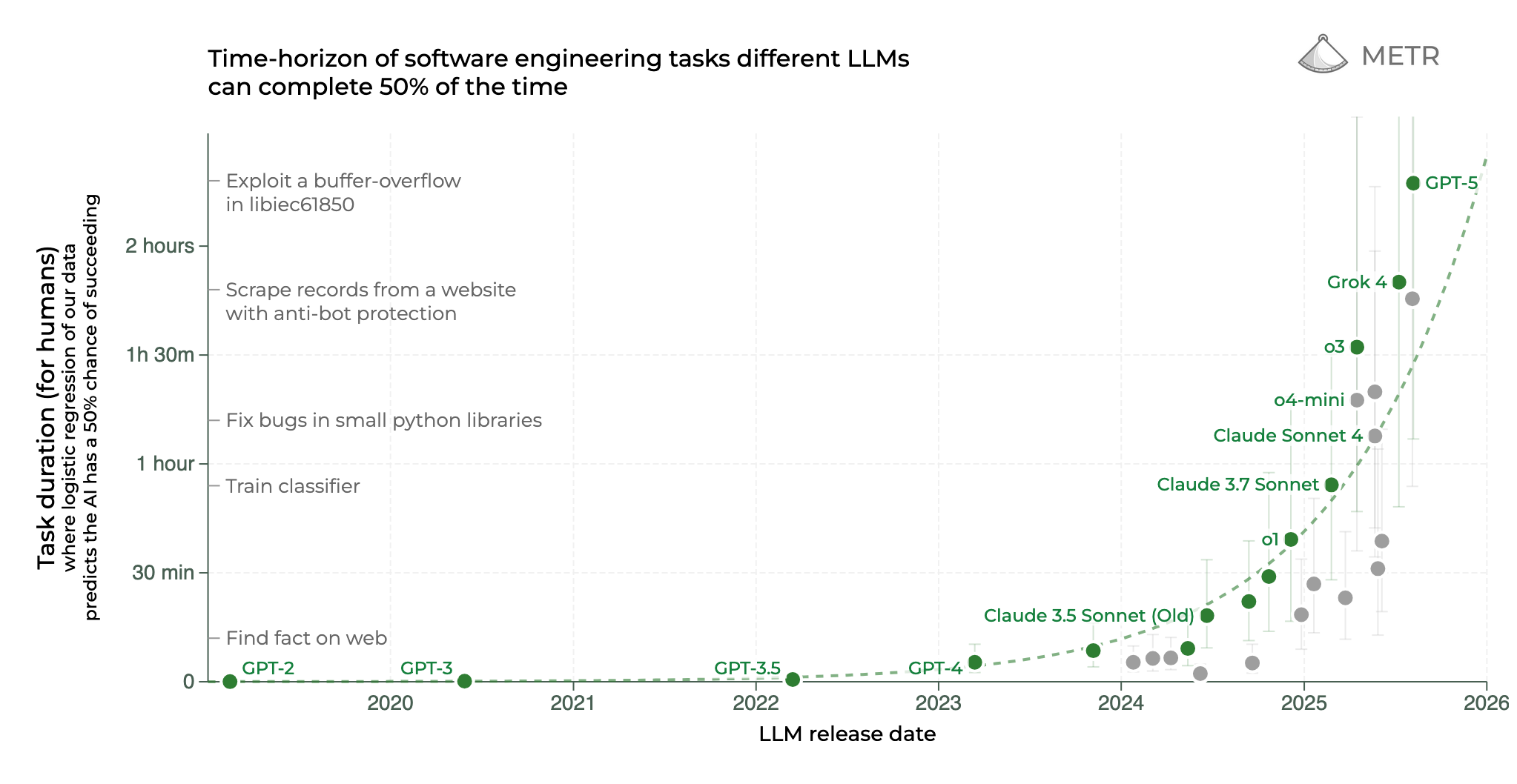

What does the state of the art for multi-turn error rates look like? METR recently published a popular chart describing how AI models are getting better at long-horizon tasks. Currently GPT-5 is at the top of the leaderboard, where it can perform ~2-hour long tasks at around a 70% success rate. Working backwards (let’s say a 2 hour task is 50+ turns) this would amount to a sub-1% error rate per action.

Doesn’t a <1% error rate per action seem suspicious to you? As a regular user of agentic coding tools (my current one is Codex CLI), I’ll eat my shoe if GPT-5 starts nailing my tasks 99.9% of the time.

My intuition derived from experience tells me that even the best AI right now isn’t even 95% likely to be correct. So where is the difference coming from? It needs a closer look at the actual paper:

Our tasks typically use environments that do not significantly change unless directly acted upon by the agent. In contrast, real tasks often occur in the context of a changing environment.

[…]

Similarly, very few of our tasks are punishing of single mistakes. This is in part to reduce the expected cost of collecting human baselines.

This is not at all like the tasks I am doing.

METR acknowledges the messiness of the real world. They have come up with a “messiness rating” for their tasks, and the “mean messiness” of their tasks is 3.2/16.

By METR’s definitions, the kind of software engineering work that I’m mostly exposed to would score at least around 7-8, given that software engineering projects are path-dependent, dynamic and without clear counterfactuals. I have worked on problems that get to around 13/16 levels of messiness.

An increase in task messiness by 1 point reduces mean success rates by roughly 8.1%

Extrapolating from METR’s measured effect of messiness, GPT-5 would go from 70% to around 40% success rate for 2-hour tasks. This maps to my experienced reality.

I am not certain that pure intelligence can solve for messiness. Robustness to environmental chaos and the fuzzy nature of reality is fundamentally about managing context well. Until we find the magic sauce that solves this, it is clear that we need a workflow that can break down our problem into units of work, with verifiable checkpoints to manage the compounding of errors.

These verifiable checkpoints need to be legible to humans.

So, what is the “right sized” unit of work?

The right sized unit of work needs to be small and describe the desired outcome concisely.

The desired outcome on completion of a unit of work needs to be human-legible. I argue that it needs to provide legible business value. Ultimately, the users of software are going to be humans (or systems that model human constructs). Therefore, an elegant way to break down a project is to model it as small units of work that provide legible business value at each checkpoint. This will serve the purpose of respecting the context window of the LLM and help manage the propagation of errors.

Software engineers have already defined a unit of work that provides business value and serve as the placeholder for all the context and negotiation of scope—User Stories. I think they are a good starting point to help us break down a large problem into smaller problems that an LLM can one-shot, while providing a concrete result. They center user outcomes, which unlike “tasks”, are robust to the messy dynamic environment of software development.

Deliverable business value is also what all stakeholders can understand and work with. Software is not built in a vacuum by developers—it needs the coordination of teams, product owners, business people and users. The fact that AI agents work in their own context environment separate from the other stakeholders hurts effectiveness and transfer of its benefits. I think this is an important gap that needs to be bridged.

| unit size | outcome of completion | |

|---|---|---|

| TODO item | small | incremental technical value |

| “Plan Mode” | large | technical value |

| Amazon Kiro Spec | small | technical value |

| User Story | small | business value |

Most AI agents today have well-functioning “planning” modes. These are good at keeping the agent on rails, but they mostly provide technical value, and not necessarily a legible business outcome. I believe planning is complementary to our idea of breaking down a project into small units of business value. My proposed unit of work can be planned with existing planning tools. And I believe this is superior to planning over a large unit of work due to the context rot issues described earlier.

Of course, plain old User Stories as described in the Agile canon is not sufficient. It needs to be accompanied by “something more” that can nudge the agents to gather the right context that serves the business value outcome of the stories. What that “something more” could look like is something we hope to answer in the coming months.

The StoryMachine experiment

To test whether user stories with “something more” can indeed serve as optimal units of work that that have the properties I described above, we are running an experiment called StoryMachine. Currently StoryMachine does not do much—it reads your PRD and Tech Specs and produces story cards. It is still early days. But we will set up an evaluation system that will help us iterate to a unit of work description that helps us build useful software effortlessly. I hope to share updates on what we find in the coming months.

I want the craft of AI-assisted development to be less effortful and less like a slot-machine. And our best lever to get there is managing the unit of work.