Underlying great creations that you love—be it music, art, or technology—its form (what it looks like) is driven by an underpinning internal logic (how it works). I noticed this pattern while watching a talk on cellular automaton and realized it's "form follows function" paraphrased from a slightly different angle. Inventing a form is a hard task, so you must approach it obliquely—by first illuminating the underlying function.

This made me realize something crucial about visual programming: it’s stuck on form, rather than letting form follow function. Visual programming has long been trapped in the node-and-wires paradigm because its designers are overly fixated on form, neglecting the underlying function that should drive it. So as a whole, the field is stuck in a local minima. How can we break out of it and how can we find a function for the field that underpins the form?

A clue from CellPond

I was watching a talk and was struck not just by the presentation but also by a specific quote from Lu Wilson in a talk about CellPond–a visual programming language that expanded my expectations for cellular automata. And that's given that I'd already seen my share of the Game of Life by John Conway and read lots of A New Kind of Science by Stephen Wolfram.

But even though Lu Wilson spent the last 10 minutes showing you the fantastic visuals, none of that was the point. The actual tasty result is that there is a virtual machine with only four operations underlying the CellPond system. And these four operations correspond with memory operations we're familiar with in CPUs: read, write, allocate, and deallocate. To me, that connection was utterly surprising. The grid of patterns (form) was informed and driven by the underlying virtual machine (function).

"I think if you were to learn from CellPond, you'd take away not just the UI—but you can take the UI too if you want. I was very surprised by this because, in all my reading of past solutions to these problems, they were all about the high-level user interface; they were about the UI. I thought I'd have to build layers upon layers of UI, but really, as soon as the low-level stuff was sorted out, the UI just figured itself out."

I wondered: how did Lu Wilson come up with the underlying function? It seemed magical. This puzzling revelation made me realize it wasn’t just about the UI—there was a deeper principle at play.

Form follows function

In the subsequent months, I kept turning it over in my head. The key lay with the opening quote.

When you figure out the low-level stuff, the UI all falls into place.

It wasn't until a drive while I was listening to Paul Graham's A Taste for Makers that I made the connection. The CellPond talk was a demonstration of the oft-repeated adage of "form follows function." Here's the relevant excerpt:

In art, the highest place has traditionally been given to paintings of people. There is something to this tradition, and not just because pictures of faces get to press buttons in our brains that other pictures don't. We are so good at looking at faces that we force anyone who draws them to work hard to satisfy us. If you draw a tree and you change the angle of a branch five degrees, no one will know. When you change the angle of someone's eye five degrees, people notice.

Honestly, I had never thought much about "form follows function." It seems obvious enough when you hear it for the first time. Sure, given an interface, why else would it express anything other than its purpose? It would seem counterproductive otherwise.

It wasn't until I was forced to invent a form did I really understood what it meant. The adage "form follows function" is for those tasked to invent the form, not for when you're given it. In my own words, it's this:

If a design is any good, how something looks, feels, and works is a naked expression of its function, its algebra, its rationality–its underlying nature. To design a form, you should not just come up with it out of thin air. You have to attack the problem obliquely and work out its function first. Once the function–the underlying nature, internal consistency, and algebra–is worked out, the form will fall out as a consequence.

Three faces of function

What I mean by "underlying nature" isn't that it exists independently of human creation; rather, every design is embedded in an environment that shapes its intrinsic properties. The function of anything useful is always in the context of its environment. When we understand the context of a well-designed thing, we understand why it looks the way it does. An animal form reflects its adaptation to the ecological niche in its environment.

By "rationality", I mean some kind of internal consistency. The function of something well-designed will have a certain repeated symmetry. Given a choice of design, it'll consistently use the same thing in as many scenarios as possible. Good game design enables a single item to serve multiple functions. The gravity gun in Half-Life 2 enables players to pick up and launch objects. It's used for turning environmental items into weapons, solving physics-based puzzles, and for navigating hard-to-reach areas. In Minecraft, the water bucket can extinguish fires, create waterfalls for safe descent, irrigate farmland, and serve as a barrier against certain enemies.

By "algebra", I mean a set of rules about how a design's components compose. Most games have a physics engine that computes how objects in a game interact with each other in space. It's a "movement calculator." Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild additionally has a chemistry engine that it uses to compute how different materials interact with each other, based on three types of rules. It's a "state calculator." Rule sets constrain the design, but if they're any interesting, in composition they lead to interesting and non-obvious implications. The game of Go can be distilled into three rules, but the implications of the rules explode the considerations of strategy that have fascinated players for a millennia.

In summary, function represents the intangible structure governing the relationships, interactions, and contextual fit of a design’s underlying components. A form can't exist outside of its function, and its function is shaped by its environment. We can observe and interact with the form directly, but not its function. We can exist in the environment, but the function is invisible to us without a lot of work to infer it.

A form not informed by function feels disjointed, inconsistent, and frustrating. Without an underlying function to underpin the form, the shape of form is simply at the inconsistent whims of the designer. Function keep designers honest about the purpose of form: in service of function. Of course you can explore and play with form independent of function, but that's the jurisdiction of art, not design.

To invent a form, start with the function

"Form follows function" is advice for people making something, especially those whose work has a very visible interface facing the end user. To invent a form, start with the function. But it's easy to make errors of two kinds, even if you already know this in your head.

The first kind of error is to pursue form without considering function. Instead, you must ignore the form, at least initially, and focus on figuring out the function first. This is largely due to the intangible nature of function. It's an easy mistake to focus on form, even far into your creative career.

This mistake is understandable. Whenever people interact with anything, their initial contact is the interface—the bridge between user and design. For anyone new to something, it's natural to start by engaging with that interface, because it's what they're most familiar with. So when they turn around to make something in that domain, they start with the interface, the form. You can see this readily: new creatives in a field start by copying the masters before finding their own voice.

It's also understandable because function is largely more abstract and more intangible than form. It's harder to get a grip on something amorphous, and you may have to start off with something concrete. It can be part of the process to draw up concrete examples first. In fact, when confronted with an unfamiliar domain, this can be quite productive in getting a handle on it. But it can be easy to forget and take a step back and ask: "what is the common underlying logic or abstraction to all these examples?" When you are able to take a step back, you're using the concrete examples as a stepping stone to figuring out the underlying function.

The error of the second kind is pursuing function without considering the user. As a warning for those that lean too far on the other side of the precipice, this doesn't mean you can ignore the end user when figuring out the function. If we could represent the utility of the underlying function as a vector, it would still need to point in the direction of the user. The underlying function must support and give context to the visible form built on top. Both are built so the direction and magnitude of their utility vector can support the user in the direction of their goals.

Too many back-end engineers misinterpret 'form follows function' as a license to design arbitrary database tables and APIs, assuming that the front end will compensate. That's how we get terrible interfaces where the end user needs to be aware of the data model to use it effectively, like Git.

When it comes to visual programming, I think it's stuck in the error of the first kind, with its focus on form.

Visual programming is not just node-and-wires

Node-and-wire diagrams have become a lazy default. Most visual language designers never ask whether those boxes and arrows genuinely help programmers. It’s a classic case of letting form precede function.

When one looks through the Visual Programming Codex, it's obvious an overwhelming majority are based on the node-and-wires model. Not just that, but there are mostly only two variations:

- The nodes represent data, and the wires represent functions

- The nodes represent functions, and the wires represent data shunted between functions.

Did many of them settle on it because it's the best visual representation to help aid the process of programming? Or did they use it because they're mimicking an existing form?

I think node-and-wires is popular because visual programming designers make the fundamental assumption that the underlying nature and logic of programming is just traditional textual programming. If that's your assumption, then you'd naturally think all you have to do is find visual representations for existing textual language constructs. Hence node-and-wires is the form you get when you take pure functions as the underlying logic underpinning the form.

On first glance, node-and-wires seem like a good fit. The wires going into a node are like the input parameters of a pure function, and the wires going out are like the output value. But what about differentiating between the definition of a function versus calling it? Often in node-and-wires visual languages, there's no separation. The definition is the application. What about passing around functions or thunks? Much of the power in pure functional programming lies in the power of higher-order functions, and I haven't seen very good node-and-wires representation of that. After decades of trying, most pure functional programming is still largely expressed in text. To me, that's damning evidence against the practice of using nodes-and-wires to model functions. Text is still the better form for expressing the underlying logic of functional programming.

Imperative programming with node-and-wires fares no better. A loop in LabVIEW gives no more advantage or clarity over writing it in text. Seeing the totality of a sequence of steps in parallel in a circuit-like diagram doesn't solve the fundamental problem with imperative programs; it doesn't help the developer understand combinatorial state explosions or state changes over time.

I think where node-and-wires have provided the biggest advantage is in specific domains in which a) there's massive value to examine intermediate data and values between transformations and b) there's a well-known visual representation of that intermediate data and value. This has been demonstrated in visual languages like Unreal Engine's Blueprint for game programming shaders and Max/MSP for sound synthesis in music. But these have been limited to these narrow domains. Visual programming has not found a foothold in general purpose programming domains.

Modeling problems

What then, if not node-and-wires? The aim here is to uncover an alternative underlying logic—one that can more effectively drive the form in visual programming. How would you go about finding another underlying function in "form follows function" if not the current programming paradigms we know? I think this is the wrong question. Although correct in direction and spirit, I think a better question is: how should we model problems that can leverage the computational power of our visual cortex?

We write programs primarily to model and solve real-world problems. We go through the exercise of encoding the problem model in programming languages, because we can automate the generation of solutions. And the reason why we keep banging on the visual programming door is because we understand intuitively that our visual cortex is an under-leveraged power tool.

The human visual cortex is a powerful pattern recognition apparatus. It can quickly compare lengths, distinguish foreground from background, recognize spatial patterns, and other amazing feats of perception, all at a glance. We leverage it in data visualizations to make sense of large quantities of data, but we haven't been able to leverage it to make sense of computational systems.

If we had a visual programming language that could leverage the human visual cortex, then at any zoom-level of abstraction, at a glance we could understand the overall structure of the program as it relates to the domain at that level of abstraction. And if we were looking at a running program, then we could get an idea of the overall state and process. Yes, we have bespoke visualizations of running programs in the form of metrics and dashboards. But we don't have a universal visual language to represent the structure or state of a program that applies to different programs.

What about text? Aren't textual glyphs a kind of visual language? Not in the way I mean. For text to be considered a visual programming language, it'd have to leverage the human visual cortex at different zoom-levels of the program. Certainly, with syntax highlighting we leverage the visual cortex and use color to distinguish between different syntactical elements. This counts. But we only get this at the level of a function. It doesn't apply when we zoom out to the overall structure of the code base. And there's certainly no zoom-out level in which we get visual understanding at the level of the problem domain.

The closest thing I can think of that might fit the bill is APL and its ilk. By condensing operators into single characters, sequences form idioms. Just as we recognize whole words rather than individual letters, idioms allow us to comprehend entire operations without parsing each symbol. So as you zoom out of the code, you can see the meaning of the code by identifying common idioms. Strangely, it seems many APL environments don't feature syntax highlighting.

So if visual programming is to be useful, I think the angle of attack is to find a way to model problems, and this might not be the same way that we model problems in textual languages–even if the underpinning implementation is all lambdas and Turing machines. So how do we model problems?

Entities and relationships

I'll say up front, I don't know what modeling problems should look like. Nonetheless, it seems there are two main aspects for any system we're interested in:

- visually representing the entities in a problem domain

- visually representing the entity relationships.[2]

Regardless of the paradigm, imperative, object-oriented, functional, or logical, there are both "entities" (structs, objects, compound values, terms) and "how they relate" (imperative processes, messages, functions, rules and predicates). If I had to take a stab at it, I'd start here.

Of the two, representing the different entities in a problem domain seems more amenable to visual programming because they're nouns. Most of the things we see around us are nouns. Hence, we can imagine that inert data representing entities would have a canonical visual representation. But even then, entities often have far more attributes than we might want to visualize at a time to understand its purpose and behavior. How do we choose what attribute is important to show? And what should be the visual form for the attribute in these entities?

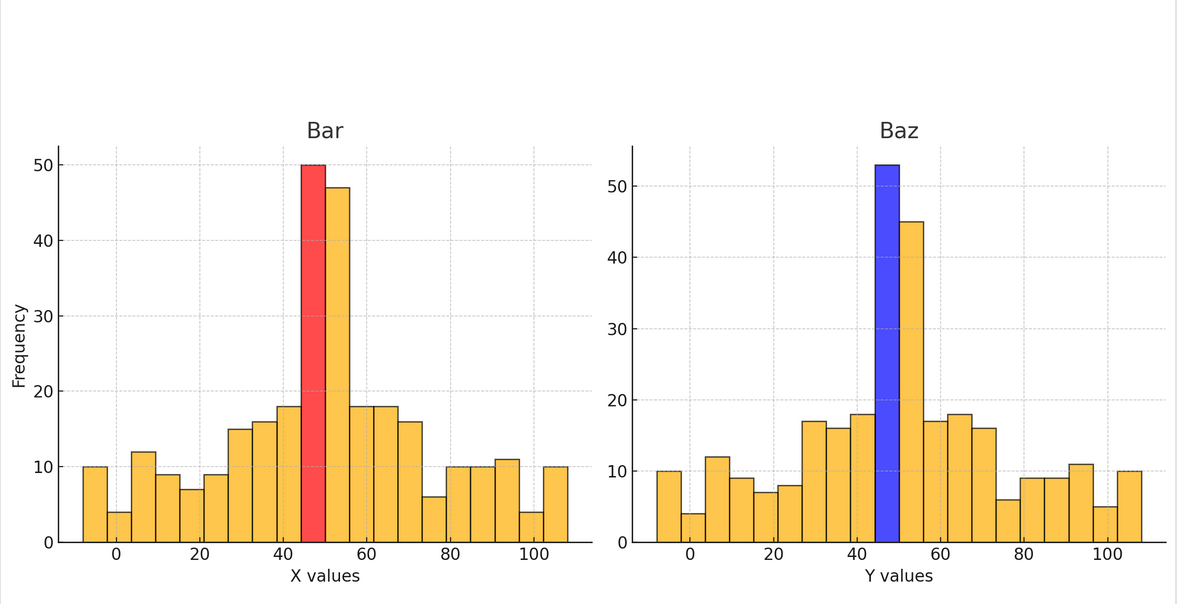

The two questions are related, but to drive the point home, I'll focus on the second one. If we have some struct with two attributes in some generic language, how would we visually represent them?

struct Foo {

bar: float,

baz: float

}We might think a universally useful representation of a collection of these instances is two histograms: one for bar and one for baz. For any given instance, its corresponding value could be highlighted on the histogram.

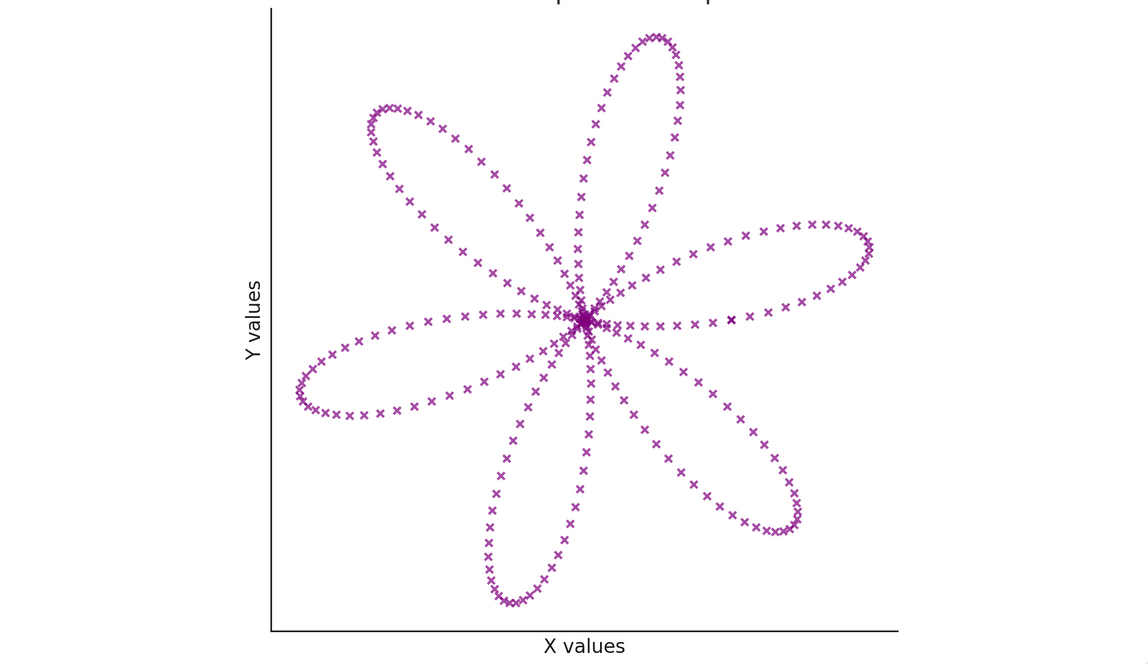

Is this useful? Answer depends on our task at hand. There's no one-size-fits-all visualization of entities. What if I told you bar is an x-coordinate and baz is the y-coordinate? Now, perhaps a visualization that's more fitting is a scatterplot where each instance is represented as an x. We put the relationship between bar and baz in a spatial relationship to see if our visual cortex could recognize a pattern.

In the histogram visualization, I wouldn't be able to use my visual cortex to discern the relationships between bar and baz traces out a flower. However, in the spatial canvas visualization, I could easily see the flower trace because by pitting bar and baz in a spatial relationship, I'm creating a mapping that makes an affordance for my visual cortex.

This only worked because there was a spatial relationship between bar and baz, especially if I know they represent x and y coordinates. We couldn't just look at the data and easily discern what visualization to use. The label and the intention of the user also give meaning to what visualization is best suited for an entity. Hence, I think there's no one-size-fits-all visualization for entities. There's no single mapping of attributes to visualizations that makes sense, unless the user's intention and goals remain fixed.

Besides entities, every program encodes relationships between its entities. How do we visually represent their relationships in a way that's illuminating at a glance without devolving into an illegible spaghetti mess? Relationships can be harder to model, because they're typically invisible to us, as they're often inferred.

Like the example with representing entities visually, representing relationships visually is likely to depend on both the goals of the user as well as the meaning of the entities at hand. I suspect a good visual representation of the relationship between two tables in a query is going to be different than a good visual representation of the relationship between two pieces of middleware in a web stack. However, I do think we can do better than a line.

The go-to representation of a relationship is often the line or an arrow, where it connects two things on the canvas together. The trouble with lines is that they doesn't scale with the visual cortex. After a couple dozen lines, we lose track of any sense of the overall relationships between entities. But I don't think this can be the only way. The visual cortex also relates visual elements if they have the same color or if they're spatially clustered together. As the previous example on a plot of bar and baz showed, relationships could be spatial, by which we can plot them spatially to reveal relationships, without directly drawing lines and arrows everywhere.

As before, it's hard to draw any generally productive conclusions on how to best visually represent relationships between entities without knowing the goal of the user as well as the meaning behind the entity and relationships we're trying to represent. The only point I'm trying to drive home is that we have more tools at our disposal besides lines and arrows, because the visual cortex is perceptive and discerning about colors, groupings, and motion. We typically use these visual elements haphazardly, if at all, rather than as a deliberate attempt to leverage it for understanding. And that's just in graphic design and data visualization. It's completely overlooked in program structure, debugging, and domain problem modeling.

At this point, those that hear entities and relationships might be drawn to ask, isn't this just object-oriented programming? It is true that object-oriented thinking trains you to identify entities in the problem domain and model their relationships through method calls and messaging. However, object-oriented programs suffer from private state whose effects are observable from the outside littered everywhere, making it hard to reason about program behavior. What I'm saying is orthogonal to and doesn't invalidate what we've learned about structuring programs in the past 3 decades.

To sum up, I'm saying the unit of representation for visually representing programs may not be the function and its input and output parameters, as node-and-wire visual programmers are likely to do. It might be something else, which can leverage the power of the visual cortex.

Computation is figuring out the next state

Modeling problems as entities and their relationships is only half the equation. By only modeling entities and their relationships, we've only described a static world. We can do that already without computers; it's commonly done on whiteboards in tech companies around the world. Every time we go up to the whiteboard with a coworker to talk through a problem, we're trying to leverage the power of our visual cortex to help us reason through it. But unlike our textual programs, whiteboards aren't computational.

If whiteboards were computational, they might show how the state of the problem changes over time, or how it changes in response to different external inputs or effects. Thus, the question is, how do we visually represent how the system state should evolve over time or in response to external inputs? [1]

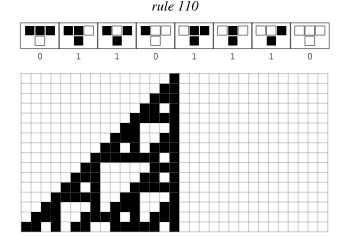

Cellular automaton systems typically express computation through rulesets. Rulesets are typically expressed as a pure functional transformation between the current state and the next state. Taking rule 110 in 1D cellular automaton as an example, the state of the next cell depends on the three cells above it. Given the three cell pattern above, this is what the cell in the next line should be. You can see this like a β-reduction, substituting symbols with other symbols until we can substitute no further, with the resulting value as our answer.

As the CellPond talk at the top of the page points out, rulesets for more complicated behaviors, like trains on tracks have a combinatorial explosion of rules. One of CellPond's innovations was to have rulesets that represent (or generates?) groups of rulesets, so that visually expressing the rulesets remains tractable for humans.

But pure functions are just mappings. Any pure function can be replaced by an equivalent infinite table of key-value pairs. Rulesets are just explicit mappings of inputs to outputs. Hence, if rulesets are to be tractable, we must be able to express not just how a single current state maps to the next state, but how entire groups of states map to a next state.

We have familiar mechanisms in textual programming to express a selection of groups of input states in a succinct way. We have boolean logic in if expressions. We have maps and filters. We have select and where clauses in SQL queries. But we have no universal and composable ways of expressing this selection of previous states and mapping them to next states. Additionally, we don't have universally recognized ways of expressing this mapping from groups of inputs to outputs for state types other than a grid of cells.

A different way forward

Certainly, it could be possible that multi-dimensional aspects of a code base would be quite hard to represent in its entirety visually. But I don't think it's a stretch to say that we lean pretty hard on the symbolic reasoning parts of our brain for programming and the visual reasoning parts of our brain are under-leveraged.

Visual programming hasn't been very successful because it doesn't help developers with any of the actual problems they have when building complex systems. I think this is a result of ignoring the adage "form follows function" and trying to grow a form out of traditional programming paradigms that fail to provide good affordances–the utility vector is pointing the wrong way–for those actual problems in complex systems. To make headway, I think we should focus on discovering underlying logic and function of how to model problems visually on a canvas–not just the entities, but also their relationships. In addition to modeling problems, we also have to discover how to model transformations and transitions of state, so our models are also computational.

We have the hardware: our visual cortex is a powerhouse for pattern recognition and spatial reasoning. We just don’t have the right computational grammar to feed it. If we want a visual programming breakthrough, we have to leave the legacy of text-based paradigms behind and unearth a new kind of function—one that only makes sense visually. Once we do, the right ‘form’ will follow so obviously, we’ll wonder why we waited so long.

[1] One way is with visual rule sets. This almost feels like declarative or logic programming. But as the Cell Pond talk at the top of the essay pointed out, unless you have a representation of rule sets that can be expanded, you suffer combinatorial explosion.

[2] Depending on who you are, this can sound either like object-oriented programming or category theory.